赵紫阳软禁期间秘密口述录音回忆录出版

wanghx

ed2k://|file|pw-zzy.7z|19024313|15AA57A93F476F1E154F59B99348DA60|h=ZYZD2JJ57WNV53MO7UDYQZIAIKHHFLUS|/

解压密码: zzy

文汇目录:

- Twitter 消息和评论

- RFA独家:赵紫阳录音回忆的历史背景(鲍 彤)

- 赵紫阳录音结集出书 专访策划者鲍彤

- BBC: 赵紫阳秘密录音回忆录将在美出版

- Washinton Post: John Pomfret: Secret Memoir Reveals Dissent From Chinese Leader

- 赵紫阳违反了共产党所信仰的主要宗旨,那就是他把心底的话给说出来了!

- Washinton Post: China's Prisoner of Conscience 赵紫阳录音英汉文本

- Excerpt 1: Tragedy

- Excerpt 2: Punishment

- Excerpt 3: Socialism

- Excerpt 4: Economic Reform

- Excerpt 5: Market Systems

- Excrpt 6: Democracy

- Excerpt 7: Foreigners

- Book Review: Perry Link: From the Inside, Out, Zhao Ziyang Continues His Fight Postmortem

- 改革历程:赵紫阳

- 纽约时报发表的赵紫阳录音英汉文本

- New York Times: Secret Memoir Offers Look Inside China’s Politics

- Washinton Post: John Pomfret: China's Zhao Details Tiananmen Debate

- BBC: 赵紫阳秘密回忆录出版内情

- 相关报道

- 赵紫阳: “六四”问题应当是非常清楚了

- 鲍彤:赵紫阳录音回忆的历史背景(一)-中国为什么非改革不可

- 鲍彤:赵紫阳录音回忆的历史背景(二)-党国领导当时开的药方里没有改革

- 鲍彤:赵紫阳录音回忆的历史背景(三) - 四川在探寻改革之路

- 鲍彤:赵紫阳录音回忆的历史背景(四) - 进入了改革年代

- 鲍彤:赵紫阳录音回忆的历史背景(五) - 赵与邓的分歧在于党和人民关系的定位上

- 鲍彤:赵紫阳录音回忆的历史背景(六) - “六四”开创了全民噤声的新局面

Twitter 消息和评论

http://twitter.com/rtmeme/statuses/1794461681RT @bbcchinese: 中共前总书记赵紫阳去世四年后,他在软禁期间秘密口述在录音带上的回忆录,本月将在美国出版。 - http://tinyurl.com/phw8dh

http://twitter.com/huaizhao/statuses/1793298999

huaizhao: 路透社報道,已故中共前總書記趙紫陽遺下了錄音帶回憶錄,趙的前秘書鮑彤證實錄音是真的。

http://twitter.com/mranti/statuses/1794612854

mranti: 《华邮》把赵前总书记的秘密录音摘录上网,并且有中英文文字记录,共有7段,很有价值下载: http://twurl.nl/da3kb5

http://twitter.com/njhuar/statuses/1803787231

njhuar: RT: @zuola: RT @ivanzhai 华邮提供赵紫阳的录音1-4,点击即下载:http: //cdn.washingtonpost.com/media/podcast/music/Clip04.mp3 更改Clip04.mp3为Clip01.mp3 即可下载第一段

http://twitter.com/zhuanwan/statuses/1794879481

zhuanwan: 赵前总书记的秘密录音片段音频版下载地址:http: //cdn.washingtonpost.com/media/podcast/music/Clip0n.mp3 ,倒数第5个字符n改为1-7,共7段

http://twitter.com/rtmeme/statuses/1803624121

rtmeme: RT @feng37: 纽约时报把赵紫阳的六三六五回忆录的录音直接放在网上 http://bit.ly/3xhRq (中文的)

http://twitter.com/blogtd/statuses/1804120928

blogtd: 听赵老师讲那过去的故事 http://hexieshangan.blog.163.com/blog/static/8991849720094153475875/

http://hexieshangan.blog.163.com/blog/static/8991849720094153475875/

赵老师音容宛在(生前自白录音) 2009-05-15 15:51

路透社发放的自白书录音 一共7段:

http://cdn.washingtonpost.com/media/podcast/music/Clip01.mp3

http://cdn.washingtonpost.com/media/podcast/music/Clip02.mp3

http://cdn.washingtonpost.com/media/podcast/music/Clip03.mp3

http://cdn.washingtonpost.com/media/podcast/music/Clip04.mp3

http://cdn.washingtonpost.com/media/podcast/music/Clip05.mp3

http://cdn.washingtonpost.com/media/podcast/music/Clip06.mp3

http://cdn.washingtonpost.com/media/podcast/music/Clip07.mp3

http://twitter.com/Ye1980s/statuses/1803546425

Ye1980s: RT @rtmeme: RT @huyong: 赵紫阳:“我们社会主义国家所实行的民主制度,完全流于形式,不是人民当家作主,而是少数人,甚至是个人的统治。” ///将死之人,其言敢真。

http://twitter.com/huyong/statuses/1802410068

huyong: 赵紫阳:“不然的话,这个国家就不可能使它的市场经济成为健康的,现代化的市场经济,也不可能实现现代的法治社会。就会象许多发展中国家,包括中国出现权 力市场化,社会腐败成风,社会两极分化严重的情况。”

http://twitter.com/huyong/statuses/1802407258

huyong: 赵紫阳:“当然将来哪一天也许会出现比议会民主制更好,更高级的政治制度,但那是将来的事情,现在还没有。基于这一点就可以说,一个国家要实现现代化,不 仅要实行市场经济,发展现代的文明,还必须实行议会民主制这种政治制度。”

http://twitter.com/huyong/statuses/1802390772

huyong: 赵紫阳:“过去对西方发达国家所实行的议会民主制,认为不是人民当家作主。苏联式的,社会主义国家所实行的代表大会制度,才能体现人民当家作主,这是比西 方议会制更高级的,更能体现民主的形式。事实上不是这么一回事。”

http://twitter.com/huyong/statuses/1802374194

huyong: 鲍彤:“赵紫阳留下了一套录音带。这是他的遗言。赵紫阳的遗言属于全体中国人。”这份遗言最震动人心的一段是:“6月3日夜,我正同家人在院子里乘凉,听 到街上有密集的枪声。一场举世震惊的悲剧终于未能避免地发生了……”

http://twitter.com/rtmeme/statuses/1802173319

rtmeme: RT @mranti: 《纽约时报》版的赵前总书记秘密录音片段的中文文字pdf版下载 http://twurl.nl/qkpeeb

http://twitter.com/hehe_night/statuses/1801819745

hehe_night: RT @doubliu: 我不知道在坦克和冲锋枪下伤亡同胞的数目。我国年年组织讨论日本侵略者杀死中国人的数目,从来没有谈论过中国人民解放军杀死本国人民的数目。--赵紫阳

http://twitter.com/doubliu/statuses/1801709126

doubliu: 党中央开了武力镇压公民的先例。二十年来,历届领导上台,都照例必须像宣誓一般,作出肯定镇压的赞美。上行下效,省、市、县、乡、村,创造了多少起官员镇 压公民的小天安门事件?有人说,一年三百六十五天几乎天天有。-- #赵紫阳

http://twitter.com/doubliu/statuses/1801630530

doubliu: 第三,将“六四”定性为反革命暴乱,能不能站得住脚?学生一直是守秩序的,不少材料说明,在解放军遭到围攻时,许多地方反而是学生来保护解放军。--赵紫 阳

http://twitter.com/hehe_night/statuses/1801514830

hehe_night: RT @amoiist: 当年赵公逝世时, 我就曾想肯定会给后人留点什么, 现在终于盼来了, 显得弥足珍贵

http://twitter.com/Mosesofmason/statuses/1800977033

Mosesofmason: 赵紫阳秘密回忆录出版内情 - http://bit.ly/4Ndwi (via... http://ff.im/2TOF4

http://twitter.com/Ye1980s/statuses/1796362327

Ye1980s: RT @bbcchinese: 美国西蒙舒斯特出版社本月将出版根据已故中国共产党前总书记赵紫阳独白口述录音翻译成的回忆录。 - http://tinyurl.com/q96fow

http://twitter.com/annpo/statuses/1796311743

annpo: Retweeting @transgression: 听了华邮公布的赵紫阳的谈话录音,真是重磅炸弹啊,一想想都好多年了,六四我还上小学……被关了十六年,老赵留了一手,死后才来复仇,证明自己的清白,厉 害!起码在留给中国人的道德遗产这一点上,老邓输了。http://is.gd/zQSC

http://twitter.com/Mosesofmason/statuses/1795922505

"华盛顿邮报" 对赵紫阳自传的两篇书评的中文版 pdf 下载 : "华盛顿邮报" 对赵紫阳自传的两篇书评的中文版 pdf 下载 http://tinyurl.com/qucqrn

http://twitter.com/zhuanwan/statuses/1795676806

zhuanwan: > @oldyumi: RT @mandarinnews RFA赵紫阳录音回忆的历史背景(鲍彤): 赵紫阳的遗言属于全体中国人。以文字形式公之于世是我的主张,事情由我主持,我对此负政治上的责任。赵紫阳录音回忆的价值,供世人公论。它的内容 http://twurl.nl/oipehs

http://twitter.com/rmack/statuses/1794950012

rmack: Retweeting @mranti: 《华邮》对赵前总书记自传书的两篇书评的中文版pdf下载: http://twurl.nl/dgxakf http://twurl.nl/w18lo6

http://twitter.com/zhuanwan/statuses/1803134622

RT @wjs2634: Zhao Ziyang alleges Li Peng 1989 scheming http://ff.im/-2U7Er

http://twitter.com/rmack/statuses/1794235224

rmack: WaPo on secret memoir of the late Zhao Ziyang, Chinese leader who was deposed after supporting student movement in 1989. http://is.gd/zNpT

http://www.rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/baotong-05142009090141.html

RFA独家:赵紫阳录音回忆的历史背景(鲍 彤)

2009-05-14

赵 紫阳留下了一套录音带。这是他的遗言。 赵紫阳的遗言属于全体中国人。以文字形式公之于世是我的主张,事情由我主持,我对此负政治上的责任。 赵紫阳录音回忆的价值,供世人公论。它的内容关系到一段正在继续影响着中国人现实命运的历史。这段历史的主题是改革。在大陆,在目前,这段历史是被封锁和 歪曲的对象。谈谈这一段历史的背景,也许对年轻的读者了解本书会有点用处。

Photo:AFP

图 片:鲍彤接受访问时手持中共前总书记赵紫阳的照片,要求政府平反六四,弥补过去的错误。(2009年4月27日法新社)

http://www.rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/zhaoziyang-05142009121836.html

赵紫阳录音结集出书 专访策划者鲍彤

2009-05-14

前 中共总书记赵紫阳软禁中的录音即将结集成书,曾担任中共中央政治局常委政治秘书的鲍彤周四就此接受本台的专访。自由亚洲电台特约记者丁小的采访报道。

鲍 彤提供

图 片:鲍彤近照(鲍彤提供)

记者:就赵紫阳的录音,听说您听过想问一下这个内容是怎样的?

鲍彤:这个录音是真实的,这个录音变成书,它所记录的材料是真实的。

记者:为什么现在出英文版,而不先出中文版呢?

鲍彤:这是我的安排,由于特殊环境而必须采取的特殊措施。如果先出中文版,被扼杀了就没有了。先出一个英文版,被国际社会认可,认为

是真实的,那么中文版就不可能被扼杀。

记者:内容里面哪些您认为非常有价值?

鲍彤:内容主要讲三个问题,一个是六四,这是大家所关心的,关于六四的真相我想没有别人能讲得那么清楚透彻;第二个问题是改革,中国从一九八零年到八九 年,赵紫阳担任国务院总理和中央财经领导小组组长,负责经济改革的时候真实的记录;第三部分就是关于中国以后的前途,赵紫阳提出一个结论,中国将来最好应 该实行议会民主制,赵紫阳认为如果没有议会民主制,市场经济不可能成为完全的市场经济,必须要求议会民主制的配合。

记者:这些录音为什么这么多年以后才出版?

鲍彤:这是赵紫阳本身被软禁所决定,他自己尚且没有自由,他的声音怎么可能有自由呢?所以只有在赵紫阳去世了,他得到了自由,然后我

们才有可能做出这样的安排,令他的声音得以面世,公诸于世。这个虽然晚了一点,但终究出版了,我认为是个非常好的事情。

记者:过程里你们有没有受到什么压力?

鲍彤:过去他们不知道这件事情当然不会有什么压力,以后我相信如果他们是依法办事的话,应该不会施加什么压力。因为我知道江泽民是中共前总书记,他出版了 自己的书,那么我想赵紫阳出版自己的书,他的合法性和江泽民是一样的,不比他少一分;中国公民在法律面前一律平等,赵紫阳的言论自由和江泽民的言论自由一 模一样,所以我认为不应该有什么压力。赵紫阳已经去世了,现在出版这本书策划者就是我鲍彤一个人,如果当局认为要追究政治责任或法律责任的话,当然应该追 究我的责任。但我也不担心,因为根据中国宪法第三十三条,公民在法律面前一律平等,我想我跟江泽民那本书的出版者同样是合法的;如果把我可以判刑、迫害, 那么对江泽民那本书的出版者同样要判刑,所以我一点都不担心。

我相信中国党和政府只要是依法办事的话,就应该给这本书以生存的空间。我希望它能更勇敢一点,让这本书的英文本以及中文本,当然现在都还没出版,都将在最 近面市,它们出版以后我希望海关不作为禁书,如果要作为禁书,如果要扫黄打非,我希望把江泽民的书也作为扫黄打非的对象,我希望一律平等,这才表示这个政 府这个党是在履行中国宪法第二条和第三十三条的精神。

记者:这本书出版以后,录音带的声音内容是否也会全部公开?

鲍彤:不可能,因为有一部分录音带是几个人的交谈,有人问紫阳回答,用这种方式处理的,为了保护录音带里出现的人免受株连。“株连”本来不是合法的名词, 但是在中国它是潜规则,它是一种不成文法,六十年来株连罪及无辜这是一个中国政治的现实。所以为了这个问题,录音带无法公布。

记者:大概是哪几年的录音?

鲍彤:一九九三年赵紫阳作了充分准备写成文字材料,但是不具备录音的条件,他当时没有录音的设备,又不愿意家人卷入这件事情里面,所以九三年他准备了详尽 的文字材料,七年以后二零零零年录音。这是我根据各种迹象做出的判断,如果将来有更新的材料我可以修改这一判断。

记者:这次出书他的家人有没有什么意见?

鲍彤:这件事情和他家人无关,和我有关,是我做的主张。不仅如此,赵紫阳当年他做录音的时候,都不让任何一个家人知道他在录音,当时实际上是这样一个情 况。

记者:六四二十周年之际推出这本书是时间上的巧合还是?

鲍彤:我知道有这个录音带的存在是去年的事情,各种工作使我不可能用更快的速度来设法出版,我已经尽了最大的努力来安排他能够出,现在能出版是非常不容易 的事情。

以上是自由亚洲电台特约记者丁小的采访报道。

http://newsvote.bbc.co.uk/chinese/simp/hi/newsid_8050000/newsid_8050100/8050151.stm

中国共产党前总书记赵紫阳去世四年后,他在软禁期间秘密口述在录音带 上的回忆录,本月将在美国出版。

赵紫阳因为在1989年支持天安门学生运动而遭罢官,随后被软禁在家中13年,直到2005年1月去世。

这部总长30个小时的录音带,是被赵紫阳的三位朋友秘密带出中国的,翻译成英语后,由美国西蒙舒斯特出版社

为回忆录写序、写前言和后记的评论家们对这部回忆录这样评价:

朴实无华

美国哈佛大学教授麦克法夸尔在赵紫阳回忆录的前言中写道:

回忆录以朴实无华、毫不自我夸耀的文字回顾他的领导生涯。

从文中可以看出,中国改革开放的总工程师实际上应该是赵紫阳,而不是邓小平。

赵紫阳在进行了无数次考察后意识到,自1978年12月邓小平上台后所作的致力于农村集体化已经不合时宜,所以他转而支持全国农村家庭联产承包制, 认为这才是农业发展和增加农民收入的办法。

赵紫阳承认,没有邓小平的支持,家庭联产承包制是不可能进行的。但这一概念上的巨大突破者是赵紫阳,并不是邓小平。

中国的内幕

哈佛的商业评论总编伊格纳休斯在绪言中说:

这是中国第一位国家最高领导人对他的高官生涯的坦率描述。他让读者看到全世界最不透明的政权之一的内幕。

读者能够从中看到这位试图让自由改革进入中国的领导人的喜怒哀乐和成功失败,他曾竭尽全力阻止天安门血腥镇压的发生。

伊格纳休斯还说,这是赵紫阳对历史回忆的版本,可能也是他为自己的辩护,希望将来有一天,新的中国最高领导人会重审他的案子,恢复他在中国共产党和 中国历史上的地位。

尽管赵紫阳已经去世,但他在回忆录中所说的话,具有使中国人聆听和反思的道德力量。

历史不会遗忘

赵紫阳最信任的秘书鲍彤的儿子鲍朴在回忆录的后记中说:

赵紫阳不想做一个空想家,他是个实用主义者,致力于解决实际困难。

他领导中国人在混乱和无序中摸索,为提高人民的生活而作出困难的选择,他尽了他的职责。

这份回忆录音是赵紫阳留给后人的遗产,将证明他不会被历史遗忘。

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/05/14/AR2009051400942.html?hpid=topnews

Washinton Post: John Pomfret: Secret Memoir Reveals Dissent From Chinese Leader

By John PomfretWashington Post Staff Writer

Thursday, May 14, 2009 9:07 AM

Zhao Ziyang violated one of the central tenets of Communist Party doctrine: He spoke out. But it is only now, four years after his death, that the world is hearing what he had to say.

In a long-secret memoir to be published in English and Chinese next week, just in time for the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square crackdown, the former head of the Chinese Communist Party claims that the decision to impose martial law around Beijing in May 1989 was illegal and that the party's leaders could easily have negotiated a peaceful solution to the unrest.

The posthumous appearance of Zhao's memoir, which he dictated onto audiotapes and the publisher has titled "Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang," marks the first time since the establishment of the People's Republic of China 60 years ago that a senior Chinese leader has spoken out so directly against the party and its system.

Reaching from the grave, Zhao pillories a conservative wing of the party for missteps that led to the bloody crackdown, which began after dark on June 3, 1989, and left hundreds dead. Few in China's leadership at the time escape Zhao's criticism. He castigates Deng Xiaoping, the man credited with opening China to the West and launching its economic reforms; Li Peng, the dour premier at the time of the Tiananmen tragedy; Deng Liqun, a hard-line party theoretician; Li Xiannian, a former vice president; and even Hu Yaobang, Zhao's longtime ally, whose death April 15, 1989, touched off the student-led protests.

But Zhao's memoir also constitutes a broader challenge to the generally accepted version of history, especially in China, that places Deng at the center of the economic reforms that have turned China into a global economic power. While acknowledging that none of the reforms "would have been possible without Deng Xiaoping's support," Zhao depicts Deng as more of a benevolent godfather than a hands-on architect. Much of the critical design -- such as dismantling agricultural communes, mapping out China's hugely successful export-led growth model and conjuring up ideological sleights-of-hand that allowed China's Communists to embrace capitalism -- was left to Zhao. In China, Zhao's role in the momentous economic changes and political events that led up to the Tiananmen crackdown have been airbrushed from history. "Prisoner of the State" is his attempt to place himself back in the picture.

"Reading Zhao's unadorned and unboastful account of his stewardship, it becomes apparent that it was he rather than Deng who was the actual architect of reform," wrote Roderick MacFarquhar, a professor of Chinese history at Harvard University, in a foreword to the book.

It has long been known from numerous accounts that Zhao opposed the decision to suppress the student-led demonstrations but was overruled by China's other top leaders. Purged from his post as general secretary of the Communist Party just days before the crackdown, Zhao spent the next 16 years, until his death in 2005, as the most prominent "non-person" in the world -- "consigned," as he says in the memoir, "to oblivion through silence."

Under virtual house arrest, in 1999 he secretly started making cassette recordings with friends, according to Bao Pu, one of the editors of the memoir for the publisher, Simon & Schuster. Bao Pu is the son of Bao Tong, a top political aide to Zhao who was jailed for six years after the crushing of the Tiananmen Square protests. Over the course of a year or so, he said in an interview, Zhao recorded roughly 30 tapes in a game of cat-and-mouse with security agents stationed at his home in a courtyard in central Beijing.

Initially, Zhao made the tapes on the rare occasions he was allowed to leave his home. But that proved perilous, because each time Zhao ventured out, he was wrapped in a security bubble and confronted at his destination by more police. So Zhao continued the project at home, passing completed tapes to trusted visitors. Bao Pu first learned of the tapes following Zhao's death Jan. 17, 2005; it took several years to amass all of them and to gain permission from people close to Zhao to publish the memoirs, he said.

"Prisoner of the State" might enrage China's Communist leaders who, despite their nation's economic success, remain vigilant about any potential challenge to the party's legitimacy. When Zhao died in 1995, the party's leaders convened emergency meetings to ensure that his death would not touch off pro-democracy demonstrations or a renewed debate about the bloodshed at Tiananmen Square. TV and radio were banned from reporting the death. Newspapers could only use a one-sentence obituary that referred to Zhao as "comrade."

Central to Zhao's memoir is his depiction of Deng, the power behind the opening of China to the West. Deng believed strongly, Zhao says, in market reforms. But he also obsessively opposed what he called "bourgeois liberalization," or Western influences. In a revealing chapter, Zhao says that Deng often spoke about "political reform," but that what he really meant were measures "precisely intended to further consolidate the Communist Party's one-party rule." Zhao describes Deng as a "mother-in-law" riding herd over senior officials constantly battling for his attention, particularly during the nasty and often petty competition between China's leaders in the run-up to the Tiananmen crackdown.

China's official explanation of the bloodshed is that, with hundreds of thousands of people occupying the central square in Beijing, the situation bordered on chaos and the party had no real choice but to clear the square by force. Zhao's counterpunch is that bumbling moves by the hardliners, led by Li Peng, created the chaos. "If the right measures had been taken," he contends "there would not have been such dire results."

Following Hu Yaobang's death April 15, 1989, students who believed that conservatives in the party had unfairly treated the more liberal Hu began demonstrating. Zhao took a soft line against the protests and, he writes, they had started to die down after about a week. Then, on April 26, while Zhao was visiting North Korea, Li Peng masterminded a meeting of the Politburo Standing Committee during which Li and others convinced Deng that the protests threatened the party's rule. Li then ordered the publication of an editorial in the People's Daily that termed the protests "premeditated and organized turmoil with anti-Party and anti-socialist motives."

Li thought the editorial would cower participants, Zhao writes. Instead, "those who were moderate before were then forced to take sides with the extremists," and the marches ballooned to more than 10,000 people in Beijing and spread nationwide. On his return to China, Zhao attempted to make peace with the protesters, offering dialogue with student groups and the establishment of a special commission to investigate corruption charges.

But, Zhao writes, "Li Peng and others in his group actively attempted to block, delay and even sabotage the process."

Zhao requested a meeting with Deng to try to convince China's leader that they needed to retract the April 26 editorial. On May 17, he went to Deng's home, thinking it was going to be a private meeting. Instead, the whole Politburo Standing Committee was present. Zhao advocated modifying the editorial. President Yang Shangkun suggested imposing martial law. Ultimately, Deng decided on martial law; there was no vote, according to Zhao.

The question of whether the Politburo's five-member Standing Committee took a vote is the only place where Zhao's version of events clashes significantly with the one provided in "The Tiananmen Papers," a collection of party documents published in 2001 that is considered the most definitive previous account of the crackdown. "The Tiananmen Papers" reported that there was a split vote of 2-2, with one abstention, and that retired Communist Party leaders were called in to decide.

Zhao's contention is that because there was no vote, the crackdown was illegal, even by the party's own rules. And once again, he contends, the hardliners around Li Peng had miscalculated. The martial law declaration prompted even bigger protests.

"A more intense confrontation was made inevitable," Zhao writes. "On the night of June 3rd while sitting in the courtyard with my family, I heard intense gunfire. A tragedy to shock the world had not been averted, and was happening after all."

Zhao's book is not just about the past. In a final chapter he writes of his metamorphosis from a cautious reformer who believed in tweaking China's system to one who advocated parliamentary democracy. China should move slowly in that direction, he writes, but "it would be wrong if our party never makes the transition from a state that was suitable in a time of war to a state more suitable to a democratic society."

Still, 20 years after the crackdown, it is remarkable how Deng's vision, as described by Zhao, of an authoritarian state oddly married with a free market holds sway in China. For three years after the tragic events at Tiananmen Square crackdown, Li Peng and the conservatives blocked market reforms. Then, in 1992, Deng reversed China's course, and all of Zhao's economic initiatives were embraced. In 1988, state-owned enterprises accounted for 60 percent of China's economy. Today, 60 percent of the economy is in private hands. China is en route to become the greatest trading nation in the world, with four of the world's top 10 busiest container ports. And yet "democratic reforms," when they are considered, are still implemented to strengthen the party's rule.

"Zhao's story reminds us of the great debates that China's leadership had about these issues," Bao Pu said, "and of his role in pushing China into the modern world."

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/world/documents/zhao_news_chinese.pdf

[原 PDF 文件无法导出为汉字,经过 OCR 识别后得到如下文本,可能有少许错字。]

THE WASHINGTON POST

Secret Memoir Reveals Dissent From Chinese Leader

By John Pomfret

Washington Post Staff Writer

Thursday, May 14, 2009; 7:37 AM

CHINESE TRANSLATION

华盛顿邮报专栏作家潘文[John Pomfret]

赵紫阳违反了共产党所信仰的主要宗旨,那就是他 把心底的话给说出来了!

然而我们也只能在他与世长辞的四年以后,才能听到这些他想对整个世界所说的话。这部长达三百多页的秘密回忆录,将会在下周以英文及中文两种语言出版,正巧

赶上六四天安门事件的二十周年纪念。中国共产党前总书记声称1 9 8 9年五月

发生在北京的解放军武力镇压行动是个错误的决定,党中央领导人应该以和平的

方式来商量解决此动乱。

在赵紫阳死后才出版的这部回忆录,是他口述录制而成的。出版商将书定名为

"改革历程”并将之称为中国人民共和国建立60以来,第一次有这样高层的领

导直接公开批评反对中国共产党以及其系统。

在书中,赵紫阳严厉批评共产党的保守派份子因为当时错误的判断而导致1 9 8

9年六月三日晚上入夜之后,发生无法挽回的流血冲突,更让数以百计的人失去

了宝贵的生命。事发之后,党内几乎没有人没受到赵紫阳的严厉谴责,他也谴责

被誉为领导中国经济改革开放的推手的邓小平;也怒斥国务院总理李鹏下令造成

这令人痛心的惨剧;批评邓力群是强硬不肯妥协的共产党理论家;指责前副主席

李先念,也包括赵紫阳的老友胡耀邦在内。引起学生抗议运动的胡耀邦则于1 9

8 9年四月1 5日过世。

但赵紫阳的回忆录不仅止于此,他还给了更多从历史的角度来看关于中国近代的

改变。他认为邓小平是经济改革的推手并将中国发展成全球经济的中心。在承认

邓小平在经济上的巨大贡献的同时,赵紫阳也细细描绘邓小平的仁慈教父形象异

于以往那种事必躬亲的形象。许多重要的政策,如解散人民公社、打造中国成为

出口成长国的形象并成功地转变中国共产党的意识型态,使其在经济上与资本主

义巧妙并存。赵紫阳其实往往才是这些政策决定的幕后推手。在中国,赵紫阳在

经济改革与政治上的重要地位却因为六四天安门事件后受到软禁长达1 5年,而

烟消云散。这本书正是试图请历史还他一个公道。

哈佛大学中国历史系的教授Roderick MacFarquhar在为这本书写序的时候表示,

[读赵紫阳那不带一丝夸耀、朴实无华的口吻所写下的回忆录,可以明显看出,

在中国经济改革开放的部份,赵紫阳才是真正引领中国走向富强之路的无名英

雄」。

赵紫阳在六四天安门事件时,反对武力血腥镇压学运的动人作风早已闻名于世,

只可惜在其它高层人士的否决驳回下,无法达成理想。他最后一次面对大众公开

发言是在武力镇压的前些天,此后便是长达1 6年的监禁生活,直到他于2005

年去世。在这段时间,他在世界瞬间消失,从中国最突出的人物渐渐成为默默无

名的人,也逐渐在生活中被世人所遗忘。

就在他被软禁在自家居所的这这些年来,他从1 9 9 9年开始与友人录制一些录

音磁带。此书其中一位编者Bao Tong之子Bao Pu,提起他父亲当年在六四之后,

因曾是赵紫阳的左右手而受到牵连,入狱长达六年之久。他告诉我们赵紫阳录在

与命令守在他北京居所庭院的保安玩猫捉老鼠的竞赛之下,间或录制了大约30

盘左右的录音。

起初,赵紫阳趁着偶尔能离开家的短暂时间录音。但这反倒增添了更多的危险,

只要每次他出门回来,都会有更多公安陪同他前往。无奈之下,赵紫阳只好在家

中持续进行这个计划,每回录制完毕就将之交予可以信赖的访客带离开。Bao Pu

头一回得知有这些磁带的存在是在2 0 0 5年一月十七号。花了长达数年的时间

才能全部搜集到,并获得赵紫阳亲近人士的同意才得以出版、公诸于世。

此书的出版,可能会激怒中国共产党中那些深怕任何潜在危险会动摇党的权威与

正统性的高层领导人。当赵紫阳于2 0 0 5年过世之时,党中央召开了紧急会议

来确保赵紫阳先生的去世消息不会引起另一波民主抗议行动或者再度引发对六

四的争议。电视与广播都禁止播出关于赵先生去世的消息。新闻也只能用一句简

单的”同志”在讣闻中称呼这位与世长辞的伟人。

赵紫阳回忆录的重要核心在描写邓小平这位中国对西方开放的幕后英雄。在书

中,他写道,邓小平固然深信市场经济可以改变中国,却也极度反对他所谓的”

中产阶级自由化”或者西潮的影响。在他的书中透露出,邓小平常提及政治的改

革,但邓小平口中所谓的政治改革其实就只是如何巩固中国共产党一党独大的政

权罢了!他也在书中提到邓小平扮演一个”婆婆”的角色,希望下头的人都为争

取他的注意力而拼个你死我活,特别是在天安门事件上头。

中国政府对六四天安门事件的官方说法是,当时有成千上万的人聚集在天安门广

场,情况变得非常混乱,因此党中央出于无奈只好使用武力镇压来驱逐人潮。然

而赵紫阳在书中却提出另一种看法,他反击地说道,天安门广场的混乱完全是来

自于党内强硬派如李鹏等人的不肯妥协姿态而导致的。倘若当初能够采取对的方

式来处理,也就不会造成这样令人悲fiA的局面。

胡耀邦于1 9 8 9年4月1 5去世之后,学生们相信胡耀邦的死亡与党内保守派

有关系。赵紫阳则采柔情策略,他认为如此一来,不出一个月人潮便会逐渐散去。

然而在4月2 6号,李鹏趁赵紫阳出访北韩之际,便幕后操纵召开党中央常务委

员会,并坚称抗议群众是出于反对党与反对社会主义的目的而有计划、有组织的

策动这些暴动。李鹏也下令要求人民日报按此刊出新闻。

赵紫阳继续写道,李鹏认为它可以用此法吓退参与抗议的群众,但结果正好与他

预期的相反,那些原本持温和立场的中立派,现在也不得不向激进派靠拢。因此

在北京市内与全国各地,竟有超过一万人以上参与此抗议行动。等到赵紫阳从北

韩出访回来,他试图采取和平方式与抗议群众达成协议,并开通政府与学生的沟

通管道来了解彼此的诉求与如何起诉腐败的贪官污吏等。

但李鹏与其党人,有意地要阻止、延迟甚至破坏这和平谈判的过程。

赵紫阳要求会见邓小平以说服为何他们必须撤回4月2 6号发出的那篇新闻稿。

因此于5月1 7时,他前往邓小平的官邸,想要私下会见邓小平。令赵紫阳惊讶

的是,党中央常务委员会已经全体在场。他提出希望修改新闻稿的建议,但杨尚

昆则持相反意见,主张用武力镇压。根据赵紫阳的说法,在没有任何投票的情况

下,邓小平最终选择了武力镇压这个提议。

共产党中央常务委员会的五名常委到底有没有投票武力镇压,这个问题是赵紫阳

这本书中和《中国[六四]真相》这本书于2 0 0 1年出版关于六四的刊物中,

唯一大相径庭的部份。《中国[六四]真相》中提到投票的结果是二对二,有一

人弃权,因此只好交由退休的共产党领导人来决定。而赵紫阳的说法却是完全没

有经过投票的程序,整个镇压的行动都是违法的。而且他再一次重申,是李鹏等

的强硬派错误估计的结果,戒严令的武装行动比实际抗议的人数更多。

“一个更激烈的对抗是不可避免的,”赵紫阳写道。“在6月3日晚上,与我

的家人坐在庭院,我听到密集的枪声响起。冲击世界的悲剧无法避免,终究还是

发生了。

”武力镇压的20年后,赵紫阳谈着邓小平的远见是多么的了不起。一个独裁主义

的国家与自由市场经济的结合在中国具有巨大的影响力。在天安门广场发生的悲

惨事件的三年后,李鹏和保守派阻止市场改革。接着在1992年,邓小平扭转中

国的进程以后,赵紫阳的所有经济举措受到人们的欢迎。1988年,国营企业占

中国经济的百分之六十。而今天,百分之六十的经济却掌握在私营企业手中。中

国逐步迈向世界上最大的贸易国家之路。世界顶级的10个繁忙的货柜港中,中国

占有其中4名。然而,考虑到“民主改革”的时候,仍为了加强党的统治而优先

考虑。“赵紫阳的故事让我们忆起了中国的领导们对这些问题的辩论”Bao Pu

说道:“也提醒着我们,他们扮演着推动我国建设现代化的重要角色。

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/world/interactives/zhao-ziyang-audio/1.html?hpid=topnews

washingtonpost.com > World > China's Prisoner of Conscience

Washinton Post:

China's Prisoner of Conscience 赵紫阳录音英汉文本

The secret journals of Zhao Ziyang, once China's best hope for economic

and political reform, surface in a new book.6月3日夜,我正同家人在院子裏乘凉,聽到街上有密集的槍聲。一場舉世震驚的悲劇終于未能避免地發生了。

“六四”悲劇三年後,我記下了這些材料,這場悲劇已經過去好多年了。這場風波的積極分子,除少數人逃出國外,大部分人被抓、被判、被反覆審問。情况現在應 當是非常清楚了,應該說以下三個問題可以回答了:

第一,當時說學潮是一場有領導、有計劃、有預謀的“反黨反社會主義”的政治鬥爭。現在可以問一下,究竟是什麽人在領導?如何計劃,如何預謀的?有哪些材料 能够說明這一點?還說黨內有黑手,黑手是誰呀?

第二,說這場動亂的目的是要顛覆共和國,推翻共産黨,這方面又有什麽材料?我當時就說過,多數人是要我們改正錯誤,而不是要根本上推翻我們的制度。這麽多 年過去了,審訊中得到什麽材料?究竟是我說得對還是他們說得對?許多外出的民運分子都說,他們在“六四”前,還是希望黨往好處改變。“六四”以後,黨使他 們完全絕望,使他們和黨處在對立的方面。在學潮期間,學生提出過很多口號、要求,但就是沒有提物價問題,而當時物價問題是社會上很大的熱點,是很容易引起 共鳴的。學生們要和共産黨作對,這麽敏感的問題他們爲什麽不利用呢?提這樣的問題不是更能動員群衆嗎?學生不提物價問題,可見學生們知道物價問題涉及改 革,如果直接提出物價問題動員群衆,實際上要反對、否定改革。可見不是這種情况。

第三,將“六四”定性爲反革命暴亂,能不能站得住脚?學生一直是守秩序的,不少材料說明,在解放軍遭到圍攻時,許多地方反而是學生來保護解放軍。大量市民 阻攔解放軍進城,究竟是爲了什麽?是要推翻共和國嗎?當然,那麽多人的行動,總有極少數人混在人群裏面攻打解放軍,但那是一種混亂情况。北京市不少流氓、 流竄犯乘機鬧事,那是完全可能的。難道能把這些行爲說成是廣大市民、學生的行爲嗎?這個問題到現在應當很清楚了。

English Transcript

On the night of June 3rd, while sitting in the courtyard with my family, I heard intense gunfire. A tragedy to shock the world had not been averted, and was happening after all.

I prepared the above written material three years after the June Fourth tragedy. Many years have now passed since this tragedy. Of the activists involved in this incident, except for the few who escaped abroad, most were arrested, sentenced, and repeatedly interrogated. The truth must have been determined by now. Certainly the following three questions should have been answered by now.

First, it was determined then that the student movement was “a planned conspiracy” of anti-Party, anti-socialist elements with leadership. So now we must ask, who were these leaders? What was the plan? What was the conspiracy? What evidence exists to support this? It was also said that there were “black hands” within the Party. Then who were they?

Second, it was said that this event was aimed at overthrowing the People’s Republic and the Communist Party. Where is the evidence? I had said at the time that most people were only asking us to correct our flaws, not attempting to overthrow our political system. After so many years, what evidence has been obtained through the interrogations? Have I been proven right, or have they? Many of the democracy activists in exile say that before June Fourth, they had still believed that the Party could improve itself. After June Fourth, however, they saw the Party as hopeless and only then did they take a stand to oppose the Party. During the demonstrations, students raised many slogans and demands, but the problem of inflation was conspicuously missing, though inflation was a hot topic that could easily have resonated with and ignited all of society. If the students had intended on opposing the Communist Party back then, why hadn’t they utilized this sensitive topic? If intent on mobilizing the masses, wouldn’t it have been easier to raise questions like this one? In hindsight, it’s obvious that the reason the students did not raise the issue of inflation was that they knew that this issue was related to the reform program, and if pointedly raised to mobilize the masses, it could have turned out to obstruct the reform process.

Third, can it be proven that the June Fourth movement was “counterrevolutionary turmoil,” as it was designated? The students were orderly. Many reports indicate that on the occasions when the People’s Liberation Army came under attack, in many incidents it was the students who had come to its defense. Large numbers of city residents blocked the PLA from entering the city. Why? Were they intent on overthrowing the republic?

Of course, whenever there are large numbers of people involved, there will always be some tiny minority within the crowd who might want to attack the PLA. It was a chaotic situation. It is perfectly possible that some hooligans took advantage of the situation to make trouble, but how can these actions be attributed to the majority of the citizens and students? By now, the answer to this question should be clear.

Excerpt 2: Punishment

Former Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang's secret journals were smuggled out of China and are to be published May 19th, for the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square demonstrations.

以上幾點,就是說明1987年中央領導班子改組、耀邦辭職以後,面臨著一個聲勢浩大的反自由化運動。在這種情况下,不反是不可能的。當時有一種很大的力 量,要乘反自由化來大肆批判三中全會的路綫,要否定改革開放政策。而我如何頂住這股勢力,如何把反自由化控制起來。不使擴大化,不涉及經濟領域;儘量縮小 範圍,儘量减少一些思想混亂,這是一個方面。再一個方面就是對人的處理的問題。要不要處理人、傷害人。如何少處理人,不過多傷害人,這也是我當時面對最頭 痛的問題。

反自由化以來,一些老人們勁頭很大,極左勢力也很大,想要整很多人。鄧小平一向主張對黨內一些搞自由化的人作出嚴肅處理。王震等其他幾位老人也是如此。鄧 力群、胡喬木等人更是想乘機把這些人置于死地而後快。在這種情况下,如何在這次反自由化中儘量少傷害一些人,保護一些人,即使沒法避免也力求傷害得輕一 些,這是一件比較麻煩的事情。一開始,在制定中央四號文件時,爲了少傷害一些人,對如何處理在反自由化中犯錯誤的人作出了嚴格的規定。文件提出:需要在報 刊上點名批判和組織處理的,只是個別公開鼓吹資産階級自由化、屢教不改而影響很大的黨員,並且應經中央批准。還指出,對有些持系統錯誤觀點的人,可以在黨 的生活會上進行同志式的批評,允許保留意見,采取和緩的方式。我在宣傳部長會議上和其他場合還講了在思想文化領域要團結絕大多數人的問題,指出包括有這樣 或那樣片面錯誤觀點的人都要團結。我還指出,在從事思想理論文化領域工作的黨員中,既鮮明堅持四項基本原則,又熱心改革開放的人固然不少,但也有些人擁護 四項基本原則,而有些保守僵化;也有些人熱心改革開放,而講了些過頭的話,出格的話。既不要把前者看成是教條主義,也不要把後者看成是自由化分子,都是要 教育團結的人。我當時有意識地强調反自由化時把有點自由化錯誤的人和有點僵化保守的人,都說成屬于認識上的片面性,就是爲了儘量避免或少傷害人。

English Transcript

Another issue was how to deal with people implicated in all of this. The Anti-Liberalization Campaign was not just a theoretical issue. My biggest headaches came from the issues of whether to punish people, how to reduce the harm done to people, and how to contain the circle of people being harmed. From the beginning of the campaign, some Party elders were also very enthusiastic and wanted to punish a lot of people. Deng Xiaoping had always believed that those who proceeded with liberalization within the Party should be severely punished. Wang Zhen and other elders believed this as well. People like Deng Liqun and Hu Qiaomu were even more eager to take the opportunity to destroy certain people and take pleasure in the aftermath.

Under these circumstances, it was difficult to protect certain people, or limit the number being hurt or even to reduce the degree of harm that was done. Hence when it was drafted, the Number Four Document set strict limits on the punishment of those designated by the campaign as having made mistakes. The document defined this as: “Punishments that will be publicized and administrative punishments must first be approved by the Central Committee, and are to be meted out to those few Party members who openly promote bourgeois liberalism, refuse to mend their ways despite repeated admonitions, and have extensive influence.” The document also stated, “For those who hold some mistaken views, criticisms by fellow Party members may be carried out in Party group administrative meetings. They should be allowed to hold to their own views and the method of carrying out the criticism must be calm.”

At the meeting of national Propaganda Department leaders and on other occasions, I also spoke on how to win over the vast majority of people in the theoretical and cultural domains. I suggested we cooperate even with people with biased or false ideas. I pointed out, “Among Party members working in the theoretical and cultural fields, there are those who clearly uphold the Four Cardinal Principles but are a bit conservative and rigid; some are enthusiastic about reform yet have made statements that are inappropriate. We cannot just label the former as dogmatic or the latter as pursuers of liberalization. We should educate and cooperate with them all.”

When proceeding with the Anti-Liberalization Campaign, I had intentionally emphasized that we should classify those who had taken faulty liberal actions as well as those who were too conservative and rigid into the same group of people who were too biased. The purpose was to avoid or reduce the harm being done to people.

Excerpt 3: Socialism

Former Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang's secret journals were smuggled out of China and are to be published May 19th, for the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square demonstrations.

但是,我們已經實行了三十多年的社會主義,對一直遵循傳統社會主義原則的中國人民,究竟應該給個什麽說法呢?一種說法是,中國社會主義搞早了,該退回去, 重搞新民主主義;一種說法是,中國未經資本主義發展就搞社會主義,現在應當進行資本主義補課。這兩種說法雖然不能說沒有道理,但是必然會在理論上引起很大 爭論,很可能在思想上造成新的混亂。特別是這樣的提法不可能得到通過,搞得不好會使改革開放事業遭到夭折,因此不能采取。我在1987年春季考慮十三大報 告時,很長一個時期就考慮這個問題如何回答。在思考過程中我越來越覺得“社會主義初級階段”這個提法最好。它既承認、肯定了我們已搞了幾十年的社會主義的 歷史,同時由于它是個初級階段,完全可以不受所謂傳統社會主義原則的約束;可以大膽地調整超越歷史的生産關係,從越位的地方退回去,實行適合我國社會經濟 水平和生産力發展需要的各種改革政策。

English Transcript

Nevertheless, we had practiced socialism for more than thirty years. For those intent on observing orthodox socialist principles, how were we to explain this? One possible explanation was that socialism had been implemented too early and that we needed to retrench and reinitiate democracy. Another was that China had implemented socialism without having first experienced capitalism, and so a dose of capitalism needed to be reintroduced.

Neither argument was entirely unreasonable, but they had the potential of sparking major theoretical debates, which could have led to confusion. And arguments of this kind could never have won political approval. In the worst-case scenario, they could even have caused reform to be killed in its infancy.

While planning for the 13th Party Congress report in the spring of 1987, I spent a lot of time thinking about how to resolve this issue. I came to believe that the expression “initial stage of socialism” was the best approach, and not only because it accepted and cast our decades-long implementation of socialism in a positive light; at the same time, because we were purportedly defined as being in an “initial stage,” we were totally freed from the restrictions of orthodox socialist principles. Therefore, we could step back from our previous position and implement reform policies more appropriate to China.

Excerpt 4: Economic Reform

Former Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang's secret journals were smuggled out of China and are to be published May 19th, for the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square demonstrations.

也許有人會問,你過去在地方工作,怎麽對經濟改革發生興趣?我認爲中國經濟必須改革,雖然那時我也看過一些東歐經濟改革的書,但出發點不是爲了改革而改 革,主要的是我認爲中國的經濟弊端太多,人民付出的代價太大,效益太差。但弊端的根本在哪里,開始也不是很清楚。總的想法就是要提高效益。來北京後,我對 經濟工作的指導思想,明確地不是爲了追求産值多少,也不是要把經濟發展搞得多快,就是要在中國找到一個如何解决人們付出了勞動,而能得到相應的實惠的辦 法,這就是我的出發點。資本主義發達國家經濟增長2-3%就不得了了,而我們經常增長10%,但人民生活沒有得到改善。至于怎樣找到一條路子,我當時觀念 裏沒有什麽模式,沒有系統的主張。我就是希望經濟效益好,有這一條很重要。出發點就是經濟效益好,人民得到實惠。爲了這個目的,摸索來,摸索去,最後就找 到了適合我們的辦法,逐漸走出了一條路。

English Transcript

The reason I had such a deep interest in economic reform and devoted myself to finding ways to undertake this reform was that I was determined to eradicate the malady of China’s economic system at its roots. Without an understanding of the deficiencies of China’s economic system, I could not possibly have had such a strong urge for reform.

Of course, my earliest understanding of how to proceed with reform was shallow and vague. Many of the approaches that I proposed could only ease the symptoms; they could not tackle the fundamental problems.

The most profound realization I had about eradicating deficiencies in China’s economy was that the system had to be transformed into a market economy, and that the problem of property rights had to be resolved. That was arrived at through practical experience, only after a long series of back-and-forths.

But what was the fundamental problem? In the beginning, it wasn’t clear to me. My general sense was only that efficiency had to be improved. After I came to Beijing, my guiding principle on economic policy was not the single-minded pursuit of production figures, nor the pace of economic development, but rather finding a way for the Chinese people to receive concrete returns on their labor. That was my starting point. Growth rates of 2 to 3 percent would have been considered fantastic for advanced capitalist nations, but while our economy grew at a rate of 10 percent, our people’s living standards had not improved.

As for how to define this new path, I did not have any preconceived model or a systematic idea in mind. I started with only the desire to improve economic efficiency. This conviction was very important. The starting point was higher efficiency, and people seeing practical gains. Having this as a goal, a suitable way was eventually found, after much searching. Gradually, we created the right path.

Excerpt 5: Market Systems

Former Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang's secret journals were smuggled out of China and are to be published May 19th, for the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square demonstrations.

總之,當時有兩部分,一個是計劃體制外的市場經濟,一個是計劃體制內的計劃經濟。我們一方面擴大計劃外的市場經濟,另一方面逐步縮小計劃經濟的比重。在計 劃經濟和市場經濟並存的情况下,勢必是此消彼長。計劃經濟縮小减弱,市場經濟就得到擴大和加强。當時市場經濟部分主要是農業、農副産品、輕紡工業、消費品 工業,而屬于生産資料生産的,基本上掌握在國營企業手裏。一個消費品,一個生産資料,如果控制生産資料生産的企業不削弱、不縮小,不分出一部分投入市場, 新生長起來的那一部分市場經濟就無法繼續;如果生産資料生産的那一部分,一點也不允許自銷,一點也不允許進入市場——如果把小煤窑、小水泥也都統管起來的 話——那新生長的市場經濟將會因缺乏原材料而遭遇到極大的困難。所以十幾年來對計劃內經濟體制的改革,對國有企業機制的改革,儘管都沒有觸動根本,但從中 國由計劃經濟向市場經濟過渡這個意義上看,它起了不可忽視的良好作用。

English Transcript

[Eds. note: Paragraphs in italics were deleted in the editing process.]

In summary, there were two aspects: one was the market economic sector outside of the planning system, and the other was the planned economic sector. While expanding the market sector, we reduced the planned sector. While both planned and market sector existed, it was inevitable that as one grew the other shrank. As the planned sector was reduced and weakened, the market sector expanded and strengthened.

At the time, the major components of the market sector were agriculture, rural products, light industries, textiles, and consumer products. Products involved with the means of production were mostly still controlled by state-owned enterprises.

If the enterprises that controlled the means of production were not weakened or reduced, if a portion was not taken out to feed the market sector, growth could not continue for the emerging market economic sector. If no part of the means of production was allowed to be directly sold on the free market; for example, if small enterprises producing coal or concrete were all under central control; then the new emerging market sector would have run into great difficulties for lack of raw materials and supplies. Therefore, for more than ten years, though there was no fundamental change to the planned economic system and the system of state-owned enterprises, the incremental changes in the transition from planned to market economies had an undeniably positive effect.

Excrpt 6: Democracy

Former Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang's secret journals were smuggled out of China and are to be published May 19th, for the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square demonstrations.

當然將來哪一天也許會出現比議會民主制更好、更高級的政治制度,但那是將來的事情,現在還沒有。基于這一點就可以說,一個國家要實現現代化,不僅要實行市 場經濟,發展現代的文明,還必須實行議會民主制這種政治制度。不然的話,這個國家就不可能使它的市場經濟成爲健康的、現代化的市場經濟;也不可能實現現代 的法治社會。就會象許多發展中國家,包括中國出現權力市場化,社會腐敗成風,社會兩極分化嚴重的情况。

English Transcript

Of course, it is possible that in the future a more advanced political system than parliamentary democracy will emerge. But that is a matter for the future. At present, there is no other.

Based on this, we can say that if a country wishes to modernize, not only should it implement a market economy, it must also adopt a parliamentary democracy as its political system. Otherwise, this nation will not be able to have a market economy that is healthy and modern, nor can it become a modern society with a rule of law. Instead it will run into the situations that have occurred in so many developing countries, including China: commercialization of power, rampant corruption, a society polarized between rich and poor.

Excerpt 7: Foreigners

Former Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang's secret journals were smuggled out of China and are to be published May 19th, for the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square demonstrations.

Chinese Transcript

現在回想起來,中國實行改革開放實在不容易,阻力很大,顧慮很多,很多無名恐懼,給要做這些事的人帶了很多帽子。改革開放,尤其是開放很不容易。一涉及到 與外國人的關係,總怕喪權辱國,怕自己吃虧,說“肥水不流外人田”。所以我常給他們講這個道理:外國人到中國投資,他們本來就很多顧慮,我們的政策這樣不 穩定,應該說有很多風險,要怕的應該是拿錢進來的外商,我們中國政府有什麽可怕的呢?

English Transcript

In hindsight, it was not easy for China to carry out the Reform and Open-Door Policy. Whenever there were issues involving relationships with foreigners, people were fearful, and there were many accusations made against reformers: people were afraid of being exploited, having our sovereignty undermined, or suffering an insult to our nation.

I pointed out that when foreigners invest money in China, they fear that China’s policies might change. But what do we have to fear?

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/05/13/AR2009051302392.html

Book

Review: Perry Link: From the Inside, Out, Zhao Ziyang Continues His

Fight Postmortem

From

the Inside, OutZhao Ziyang Continues His Fight Postmortem

Reviewed by Perry Link

Sunday, May 17, 2009

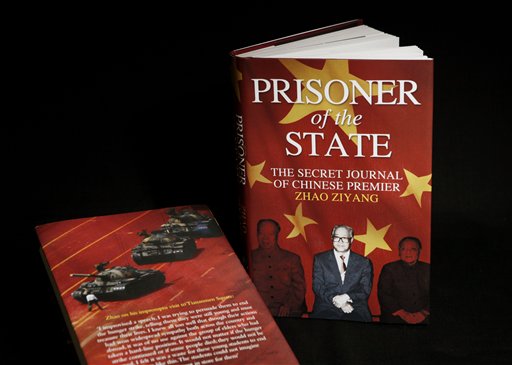

PRISONER OF THE STATE

The Secret Journal of Zhao Ziyang

Translated from the Chinese and edited by Bao Pu, Renee Chiang, and Adi Ignatius

Simon & Schuster. 306 pp. $26

[Eds. note: This story has been translated into Chinese and is available here.]

When Zhao Ziyang, the former Chinese premier who in 1989 had opposed using military force against student protesters, died four years ago, China's top leaders formed an "Emergency Response Leadership Small Group," declared "a period of extreme sensitivity," put the People's Armed Police on special alert and ordered the Ministry of Railways to screen travelers heading for Beijing. If this is how the men who rule China reacted to Zhao's death at home, how then will they respond to the posthumously published "Prisoner of the State," a book in which Zhao repeatedly attacks the stonewalling and subterfuge (and sycophancy, mendacity, buck-passing and back-stabbing) of people whose allies and heirs remain in power today?

Whatever the fallout, one element will likely stay constant: This same group of men -- mostly from a set of quarreling families bound together by common interests and long used to surviving turmoil and 180-degree policy shifts -- will remain in power. Like a seal on a rolling ball, they are good at staying on top.

But to keep its balance, the group sometimes needs to sacrifice a wayward member. In 1989, Zhao, then the Communist Party's general secretary and the major architect of China's economic reforms, was such a victim. Zhao had argued for "dialogue" over martial law as a way to handle the pro-democracy demonstrators in Beijing. On May 17, 1989, he was overruled, and on May 19 stripped of power. On June 4, soldiers fired on demonstrators in the streets of Beijing, killing hundreds. Zhao was charged with "splitting the party" and "supporting turmoil," and was confined to house arrest until his death in 2005.

Now, in "Prisoner of the State," a book timed to appear precisely 20 years since his purge, Zhao speaks from beyond the grave. He flouts the unspoken rule against public blame of others of the group. He skewers Li Peng, Li Xiannian, Yao Yilin, Deng Liqun, Hu Qiaomu and Wang Zhen repeatedly and by name. He complains that the meeting at which martial law was decided was in violation of the Party Charter because he, the general secretary, should have chaired any such meeting but was not even notified of it.

The book is based on about 30 audiotapes he discreetly recorded at home during 1999 and 2000. Clips from the tapes are to be released simultaneously with the book, and a Chinese-language transcription is supposed to appear around the same time. The material is largely consistent with what is already known from the "The Tiananmen Papers," an unauthorized compilation of government documents published in 2001, and from "Captive Conversations," a Chinese-language record of conversations between Zhao and his friend Zong Fengming, published in 2007. But the up-close-and-personal tone of the present book stands out.

Scholars will mine "Prisoner of the State" for historical nuances. It is clearer here than elsewhere that Zhao was already in serious political trouble in 1988, before the democracy movement began; and that Zhao had bickered with Hu Yaobang over economic policy as early as 1982, even though the two reformist leaders needed each other. Deng Xiaoping appears more strikingly than elsewhere as a Godfather figure: Other leaders jockey for access to him, dare not contradict him and use his words to attack one another. Yet even Deng seeks to avoid responsibility for difficult decisions. The group has dictatorial power, yet is rife with insecurity.

Sometimes these leaders -- the two dozen or so at the top -- appear oddly out of touch with the society they rule. For example, Zhao -- who was more clued in than the others -- thought that "groups of old ladies and children slept on the roads" of Beijing in order to block the entry of martial law troops. The Beijing populace did try to block the troops, but no old ladies slept on roads. Zhao lamented that the astrophysicist Fang Lizhi (who after the massacre was #1 on the government's wanted list) worsened the political atmosphere during the protests because Fang, "who was abroad, attacked Deng Xiaoping personally, by name." But Fang was not abroad; he was living on the outskirts of Beijing and deliberately observing silence. More seriously, Zhao and the others did not seem to understand that the nationwide protests arose not from superficial impressions of the West or from fleeting issues like the 1988 inflation but from a long-term and deep-seated revulsion at corruption, special privilege and the stultifying "work unit" system that Communist Party rule had brought to China.

In 1989, Zhao urged his fellow leaders to enter into reasoned dialogue with the student protesters, who, he insisted, were "absolutely not against the basic foundations of our system" but were "merely asking us to correct some of our flaws." Could it be that Zhao really believed this? Or was he using it, as the students themselves were, as protective cover? Of course the students knew that it would be dangerous -- indeed foolhardy -- to declare open opposition to the ruling system. But to conclude that they were interested only in flaws is a bit silly. When certain things could not be stated plainly in public, the students sometimes resorted to double entendre -- singing, for example, lines from the Chinese national anthem: "Rise up, oh people who would not be slaves. . . . China's most perilous hour is nigh." Even more mischievous was the singing of selected lines from the 1950s song "Without the Communist Party there would be no New China" -- where the singers intentionally left the meaning of "New China" ambiguous.

Ironically, it was Zhao's incarceration after 1989 that brought him closer to the street life of ordinary Chinese. His guards told him it was "inconvenient" for him to play golf; he had to guess at the content of unwritten rules, to deal with "made-up excuses" and to engage in vacuous word games with functionaries. His indignation at such treatment suggests that he was learning about these routine features of his society's political life for the first time.

But incarceration also provided him with time to read and reflect broadly on China's situation in history. At the end of "Prisoner of the State," we see Zhao arrive at positions more radical than any he had taken before -- positions that the Chinese government had long been calling "dissident." For instance, Zhao eventually concluded that China needs a free press, freedom to organize and an independent judiciary. The Communist Party will have to release its monopoly on power. Ultimately, China will need parliamentary democracy.

What it actually has, he observed near the end of his life, is continuing rule by "a tightly-knit interest group . . . in which the political elite, the economic elite, and the intellectual elite are fused. This power elite blocks China's further reform and steers the nation's policies toward service of itself." He saw that China's "abundant and cheap" labor had produced an economic boom. The society's rulers claim they have lifted millions from poverty, but in truth the millions have lifted themselves, through hard work and long hours, and in the process they have catapulted the elite to unprecedented levels of opulence and economic power.

The seal continues to straddle the ball -- insecure as ever, but still definitely on top.

Perry Link, who was a co-editor of "The Tiananmen Papers," is Chancellorial Chair for Teaching Across Disciplines at the University of California, Riverside.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/world/documents/zhao_review_chinese.pdf[原 PDF 文件无法导出为汉字,经过 OCR 识别后得到如下文本,可能有少许错字。]

THE WASHINGTON POST

BOOK REVIEW: PRISONER OF THE STATE

The Secret Journal of Zhao Ziyang

Translated from the Chinese and edited by Bao Pu, Renee Chiang, and Adi Ignatius

CHINESE LANGUAGE TRANSLATION

改革历程:赵紫阳

赵紫阳,中国前中央委员会总书记,于1989年六四天安门事件时,反对中共中央决定以武力镇压学生抗议的人物,在四年前与世长辞了。中国的高层领导组织

了”紧急应变小组”宣布当时为”极度敏感时期”并要求解放军戒严且对进入

北京的旅客严加检查。假如这便是北京高层面对赵紫阳先生在中国逝世的态度,

那他们又会采取何种态度来对待”改革历程”这本赵紫阳死后才出版的书?一本

描述他屡次痛斥那些使用卑鄙的手段陷害、毁谤并推诿责任的虚伪小人而如今却

仍大权在握的同盟与继承人的书呢?

且不论这事件的后续结果为何,但当初的同一群人因为共同利益而结合并且成功

地在混乱中存活下来,更能在政策一百八十度大转弯的今天持续掌权。让人不禁

佩服他们的生存之道,能令其不间断地保持在优越的地位。

而在这个族群当中,为了保持其优越地位也偶尔会牺牲一两位”道不同不相为

谋”的同志。1989年,任中央委员会总书记及当时经济改革主要推手的赵紫阳便

是其中一位壮烈的受难者。赵紫阳先生当时寄望以该党前所未有的胸怀和民主的

方式来化解冲突,却在1989年5月1 7日遭到否决,接连在19日被免去党内外一

切职务。六月四日当天,解放军开枪扫射北京街头的抗议群众,死者数以百计。

而后赵先生被控诉在关键时刻犯了“支持动乱”和”分裂党”的错误,最终在软禁监

控中度过15年的余生,于2005年逝世,享年85岁。

在这本书中,时间横跨了二十年,赵先生也似乎亲身来控诉这一切的不公,特别

指出李鹏、李先念、姚依林、邓力群、胡乔木与王占等人侵犯他身为中央委员会

总书记的权利,并在他不知情的状况下,背着他召开会议继而以武力血腥镇压民

运。

这本书的内容根据赵先生于1999年至2000年中小心翼翼所录下的三十盘录音磁

带所归纳而成。其中有些重要的录音片段以及中文翻译本也可望随之公开。而书

中资料的出处来源也多半与《中国「六四」真相》此书相同,并包含了2007年所

出版的关于赵紫阳先生与其好友Zong Fengming的中文对话录音。然而近距离的真

人对话口吻乃是本书更胜于前、也更相形引人注目的特点。

学者们可能会质疑“改革历程”此书与史学资料有细微的区别。书中更明确的道

出赵先生在1988年时,早在民运开始以前,便已卷入政治的风波。而赵紫阳与胡

耀邦,这两位既是改革者也是老战友,早在1982年经济改革政策上的看法就有所

出入。邓小平则在这群人当中明显地扮演着“教父”的角色。大家都争相接近他

又不敢忤逆他,并引用他的话语来彼此攻击。邓小平就在这群龙争霸中,尽量避

免担起这些困难的决策的风险与责任,同时也可看出在这独裁政治当中也充斥着

许多不安的氛围。

有时候这些在上位者,似乎与其所统治的社会民众有着相当大的距离。就拿赵紫

阳来说,纵然他要比任何人都亲近老百姓一些,也似乎更关心学生运动,但他却

有许多错误的印象。他认为在六四时期,许多老弱妇孺躺在大街上阻止解放军队

的进入。而事实证明,当时虽有北京民众试图阻挡解放军进入,但并无妇孺躺在

大街上。赵先生也痛惜天体物理学家方励之先生,在六四时期,成为头号中国政

府所通缉的要犯,并认为由于方励之避走他乡,在海外严厉控诉邓小平导致了政

治气氛的急速恶化。但事实上,方励之当时人并未出国,就住在北京近郊谨慎而

沉默地观望着这一切的变化。更直指核心的问题是赵紫阳与其它的高层领导似乎

完全没意识到这回全国性的抗议的根本问题,并不仅仅只是对西方民主思潮的肤

浅向往,也并非单单只是出于对1988年的通货膨涨有所不满;更近一步的说,是

出于对腐败特权和共产党所提出无用的“单位系统”所产生出根深抵固的深恶痛

绝。

1989年时,赵紫阳曾力劝其它高层领导与抗议学生进行和平对谈。他在当时坚信,

抗议的群众绝对不是”反对党的政治与领导”而单单只是要求”改正小小的瑕

疵与漏洞”。我们不禁要问,赵紫阳本人真的相信这想法?还是他只是运用这点

来当作学生运动的掩护?当然学生们明白与领导阶层对立的白热化将会是一件

多么莽撞、危险的事。然而仅只是把学运归结成”漏洞与瑕疵的改善”似乎也有

点过于天真。当某些话不能在公众面前说白,学生们自然求助于运用这些”双关

语”,正如同他们所唱的中华人民共和国国歌「义勇军行进曲」中的歌词“起来!

不愿做奴隶的人们!”“中华民族到了最危险的时候,每个人被迫着发出最后的

吼声”等等。更有些淘气、促狭的歌词像“没有共产党就没有新中国”,而”新

中国”三个字却被唱歌的人特意地趋于模棱两可了。

讽刺地是,赵紫阳在1989年后被监控软禁反而让他更贴近市井小民的生活。他的

守卫告诉他,打高尔夫球似乎有些”不方便”使他必须猜想那些并不是白纸黑字

的规定到底是什么?而他必须用哪些“借口”以及挖空心思在使用哪些华丽却

空泛的词藻来跟政府官员们打交道。他对这不平待遇的愤怒可以看出,他似乎这

才头一回学到社会的政治生活中所需的繁文缛节。

也正是因为受到软禁,他也才有充足的时间能阅读并广泛地反映出当时中国在历

史上的局面与情势。在这本书的最后,可以看出赵紫阳先生以一种他前所未有的、

与中国政府唱反调的激进角度提出他的看法。他断定中国未来会走向一种新闻自

由、集会自由以及独立的司法系统的道路。共产党也将会释出多年来垄断的大权。

中国最终会形成一种议会民主的政体。

而在生命的最终,他才观察归纳出中国政权总是由一群在政治、经济与智力上的

菁英份子所领导,而他们之间也充满着利害关系。这些精英把持着国家的政权窃

为私用,也因而阻挡了国家的改革与进步。他也指出中国经济上的进展其实是由

于这些丰富而廉价的劳动力所带来的。社会的统治者夸耀他们自己让百万人摆脱

贫困;而恰恰相反的是,这几百万人其实是通过自己长时间地努力工作来脱贫的。

在这样的过程中,这些人向上的动力,无形中促使经济有了空前的成长、创造出

丰硕的成果与财富。

而这些上层菁英份子,即使感受着动荡不安,仍旧坐稳高位,控制着整个中国的

未来。

林培瑞,《中国「六四」真相》共同编辑,现任加州大学河滨分校Teaching Across

Disciplines主任

纽约时报发表的赵紫阳录音英汉文本

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/15/world/asia/15zhao-transcript.htmlThe following are audio excerpts from recordings made by Zhao Ziyang, the purged Communist Party chief and former prime minister of China, who was removed from power in 1989 after he opposed the use of force against democracy protesters in Tiananmen Square.

[7段录音和 Washinton Post 的估计是一样的]

Transcript of Mr. Zhao's Audio Clips in Mandarin(PDF) http://graphics8.nytimes.com/packages/pdf/world/Zhao-transcript.pdf

录音谈话英汉文记录。繁体,和 Washingtonpost 的基本相同。PDF 内是图片格式。

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/15/world/asia/15zhao.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/15/world/asia/15zhao.html?pagewanted=all

New York Times: Secret Memoir Offers Look Inside China’s Politics

In May 1989, as he feuded with hard-line party rivals over how to handle the students occupying Tiananmen Square, China’s Communist Party chief requested a personal audience with Deng Xiaoping, the patriarch behind the scenes.

China Holds an Ex-Leader of ’89 Rallies, Family Says (May 14, 2009)

The party chief, Zhao Ziyang, was told to go to Mr. Deng’s home on the afternoon of May 17 for what he thought would be a private talk. To his dismay, he arrived to find that Mr. Deng had assembled several key members of the Politburo, including Mr. Zhao’s bitter foes.

“I realized that things had already taken a bad turn,” Mr. Zhao recalls in a secretly recorded memoir only now coming to light — a rare first-person account of crisis politics at the highest levels of the Chinese Communist Party.

From Mr. Deng’s impatient body language and the scathing attacks he received from his rivals, Mr. Zhao says in the memoir, which is now being published in book form, it was obvious that Mr. Deng had already decided to overrule Mr. Zhao’s proposal for dialogue with the students and impose martial law.

“It seems my mission in history has already ended,” Mr. Zhao recalls telling a party elder later that day. “I told myself that no matter what, I would not be the general secretary who mobilized the military to crack down on students.”

As Mr. Zhao anticipated, he was immediately sidelined and soon vilified for “splitting the party.” He was purged and placed under house arrest until his death in 2005.

But in this long, enforced retirement, it turns out, Mr. Zhao secretly recorded his own account, on 30 musical cassette tapes that were spirited out of the country by former aides and supporters, of his rise to national power in the 1980s, his battles with the old guard, and his alliance and tussles with Mr. Deng as he loosened Soviet-style controls and helped put China on a path to the dynamic economic power it has become today.

Mr. Zhao also tells how he was outmaneuvered during the lengthy student-led pro-democracy demonstrations in the spring of 1989, setting up his ouster shortly before the military crackdown on June 4 of that year.

One striking claim in the memoir, scholars who have seen it said, is that Mr. Zhao presses the case that he pioneered the opening of China’s economy to the world and the initial introduction of market forces in agriculture and industry — steps he says were fiercely opposed by hard-liners and not always fully supported by Mr. Deng, the paramount leader, who is often credited with championing market-oriented policies.

In the late 1970s, as the party chief in Sichuan Province, Mr. Zhao had started dismantling Maoist-style collective farms. Mr. Deng, who had just consolidated power after Mao’s death, brought him to Beijing in 1980 as prime minister with a mandate for change. Mr. Zhao, who like other Chinese leaders had little training in or experience of market economics, describes his political battles and missteps as he tried to give more rein to free enterprise.

Roderick MacFarquhar, a China expert at Harvard who wrote an introduction to the new book, said it had given him a new appreciation of Mr. Zhao’s central role in devising economic strategies, including some, like promoting foreign trade in coastal provinces, that he had urged on Mr. Deng, rather than the other way around.

“Deng Xiaoping was the godfather, but on a day-to-day basis Zhao was the actual architect of the reforms,” Mr. MacFarquhar said in an interview.

Recording over children’s songs and Beijing Opera performances on the cassettes in his guarded compound just north of Tiananmen Square, Mr. Zhao describes in generally modest terms his tenure as prime minister and then party secretary.

Mr. Zhao had initially wrote notes and then around 2000, encouraged by three sympathetic former officials who were allowed to visit him, decided to tape his memoirs, which he did partly in the presence of those supporters, said Bao Tong, a former close adviser to Mr. Zhao who remains under tight surveillance in Beijing.

Two of the former officials have since died, but one of them, Du Dao-zheng, a former senior official who oversaw press and publications, arranged for a copy of the tapes to be smuggled to Hong Kong. Mr. Du, who lives in China, decided in recent weeks to openly acknowledge his role in a statement that is quoted in the forthcoming Chinese edition of the memoir but not available in time for the English edition.

Mr. Bao, in an interview this week, called the memoir “very rare historical material” that “belongs to all the people of China and to the world.” He said that the voice was unmistakably that of Mr. Zhao and that the memoir’s authenticity was not in doubt.

Nearly 20 years after the crackdown and Mr. Zhao’s fall, the edited transcripts are being published by Simon and Schuster in a book, “Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang,” that will be formally released in the United States on May 19. A Chinese-language edition is being published in Hong Kong.

“This is the first time that such a high Chinese leader has been in a position to tell the truth,” said Bao Pu, a son of Bao Tong who is an editor of the book and a translator of the English-language edition. “At that point, the truth is all he had.”

Also credited as translators and editors are Renee Chiang, a publisher in Hong Kong, and Adi Ignatius, an American journalist who covered China in the 1980s.

Although the tumult of 1989 is distant for many Chinese, it remains a forbidden subject, heavily censored on the Internet and rarely if ever mentioned in the state-run media. Beijing authorities are likely to be unhappy with Mr. Zhao’s airing of inside conflicts as well as his conclusion, arrived at in isolation after he left power, that China must turn toward parliamentary democracy if it is to tackle corruption.

In a sharp break with Chinese Communist tradition, even for dismissed officials, Mr. Zhao provides personal details of tense party sessions. He attacks several officials, especially his archrival, the conservative former prime minister Li Peng, who fiercely opposed or, in his view, betrayed him. He describes how they schemed to turn Mr. Deng against him.

Mr. Zhao said that in 1989 he argued that most of the demonstrating students “were only asking us to correct our flaws, not attempting to overthrow our political system.”

These efforts to defuse tensions were “blocked, resisted, and sabotaged by Li Peng and his associates,” Mr. Zhao said.

Perry Link, emeritus professor of Chinese studies at Princeton who was in Beijing in 1989, said: “Laying bare the personal animosities from such a high position is something new here. It’s certainly the element that will send officials in Beijing through the roof.”

The debate over how to respond to protesting students was part of a continuing struggle over economic and political change. “What becomes clear in these tapes is that in the minds of Chinese leaders, Tiananmen was a continuation of their battles through the 1980s,” said Bao Pu, who is also a rights advocate and an editor in Hong Kong.

By forcing out Mr. Zhao and restoring a political grip that remains largely in place today, the conservatives squelched hopes that China’s economic reforms would be accompanied by systematic political change. But they were also surprised by the popular revulsion over the crackdown.

With the society in turmoil and especially after seeing the collapse of the Soviet Union, Mr. Deng began pressing even harder, in his waning years, for market-style changes, or what he renamed “socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

Despite his economic triumphs, Mr. Zhao may be remembered most for his futile effort to head off violence in 1989. In the tapes, he describes how he learned that the army had started its bloody march to the square at the heart of Beijing.

“On the night of June 3rd, while sitting in the courtyard with my family, I heard intense gunfire,” Mr. Zhao said.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/story/2009/05/14/ST2009051401023.html?sid=ST2009051401023

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/05/14/AR2009051400942_pf.html

Washinton Post: John Pomfret: China's Zhao Details Tiananmen Debate

Posthumous Memoir Castigates PartyBy John Pomfret

Washington Post Staff Writer

Friday, May 15, 2009

Zhao Ziyang violated one of the central tenets of Communist Party doctrine: He spoke out. But it is only now, four years after his death, that the world is hearing what he had to say.

In a long-secret memoir to be published in English and Chinese next week, just in time for the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square crackdown, the former head of the Chinese Communist Party claims that the decision to impose martial law around Beijing in May 1989 was illegal and that the party's leaders could easily have negotiated a peaceful solution to the unrest.

The posthumous appearance of Zhao's memoir, which he dictated onto audiotapes and the publisher has titled "Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang," marks the first time since the establishment of the People's Republic of China 60 years ago that a senior Chinese leader has spoken out so directly against the party and its system.

Reaching from the grave, Zhao pillories a conservative wing of the party for missteps that led to the bloody crackdown, which began after dark on June 3, 1989, and left hundreds dead. Few in China's leadership at the time escape Zhao's criticism. He castigates Deng Xiaoping, the man credited with opening China to the West and launching its economic reforms; Li Peng, the dour premier at the time of the Tiananmen tragedy; Deng Liqun, a hard-line party theoretician; Li Xiannian, a former president; and even Hu Yaobang, Zhao's longtime ally, whose death on April 15, 1989, touched off the student-led protests.

But Zhao's memoir also constitutes a broader challenge to the generally accepted version of history, especially in China, that places Deng at the center of the economic reforms that have turned China into a global economic power. While acknowledging that none of the reforms "would have been possible without Deng Xiaoping's support," Zhao depicts Deng as more of a benevolent godfather than a hands-on architect. Much of the critical design -- such as dismantling agricultural communes, mapping out China's hugely successful export-led growth model and conjuring up ideological sleights-of-hand that allowed China's Communists to embrace capitalism -- was left to Zhao. In China, Zhao's role in the momentous economic changes and political events that led up to the Tiananmen crackdown have been airbrushed from history. "Prisoner of the State" is his attempt to place himself back in the picture.

"Reading Zhao's unadorned and unboastful account of his stewardship, it becomes apparent that it was he rather than Deng who was the actual architect of reform," wrote Roderick MacFarquhar, a professor of Chinese history at Harvard University, in a foreword to the book.

'Oblivion Through Silence'

It has long been known from numerous accounts that Zhao opposed the decision to suppress the student-led demonstrations but was overruled by China's other top leaders. Purged from his post as general secretary of the Communist Party just days before the crackdown, Zhao spent the next 16 years, until his death in 2005, as the most prominent "nonperson" in the world -- "consigned," as he says in the memoir, "to oblivion through silence."

Under virtual house arrest, in 1999 he secretly started making cassette recordings with friends, according to Bao Pu, one of the editors of the memoir for the publisher, Simon & Schuster. Bao Pu is the son of Bao Tong, a top political aide to Zhao who was jailed for six years after the crushing of the Tiananmen Square protests. Over the course of a year or so, the younger Bao said in an interview, Zhao recorded roughly 30 tapes in a game of cat-and-mouse with security agents stationed at his home in a courtyard in central Beijing.

Initially, Zhao made the tapes on the rare occasions he was allowed to leave his home. But that proved perilous, because each time Zhao ventured out, he was wrapped in a security bubble and confronted at his destination by more police. So Zhao continued the project at home, passing completed tapes to trusted visitors. Bao Pu first learned of the tapes following Zhao's death on Jan. 17, 2005; it took several years to amass all of them and to gain permission from people close to Zhao to publish the memoir, he said.

"Prisoner of the State" may enrage China's Communist leaders, who, despite their nation's economic success, remain vigilant against any potential challenge to the party's legitimacy. When Zhao died, party leaders convened emergency meetings to ensure that his death would not touch off pro-democracy demonstrations or a renewed debate about the bloodshed at Tiananmen Square. TV and radio were barred from reporting the death. Newspapers could use only a one-sentence obituary that referred to Zhao as "comrade."

Party Miscalculations

Central to Zhao's memoir is his depiction of Deng, the power behind the opening of China to the West. Zhao describes Deng as a "mother-in-law" riding herd over senior officials constantly battling for his attention, particularly during the nasty and often petty competition between China's leaders in the run-up to the Tiananmen crackdown.

China's official explanation of the bloodshed is that, with hundreds of thousands of people occupying the central square in Beijing, the situation bordered on chaos and the party had no real choice but to clear the square by force. Zhao's counterpunch is that bumbling moves by the hard-liners, led by Li Peng, created the chaos.

Following Hu Yaobang's death on April 15, 1989, students who believed that conservatives in the party had unfairly treated the more liberal Hu began demonstrating. Zhao took a soft line against the protests and, he says in the book, they started to die down. Then, on April 26, while Zhao was visiting North Korea, Li Peng masterminded a meeting of the Politburo Standing Committee during which Li and others convinced Deng that the protests threatened the party. Li then ordered publication of an editorial in the People's Daily that termed the protests "premeditated and organized turmoil with anti-Party and anti-socialist motives."

Li thought the editorial would cower participants, Zhao says. Instead, "those who were moderate before were then forced to take sides with the extremists," and the marches ballooned to more than 10,000 people in Beijing and spread nationwide. On his return to China, Zhao attempted to make peace with the protesters, offering dialogue with student groups and the establishment of a special commission to investigate corruption charges.

But, Zhao says, "Li Peng and others in his group actively attempted to block, delay and even sabotage the process."

Zhao requested a meeting with Deng to try to convince China's leader that they needed to retract the April 26 editorial. On May 17, he went to Deng's home, thinking it was going to be a private meeting. Instead, the whole Politburo Standing Committee was present. Zhao advocated modifying the editorial. President Yang Shangkun suggested imposing martial law. Ultimately, Deng decided on martial law; there was no vote, according to Zhao.

The question of whether the Politburo's five-member Standing Committee took a vote is the only place where Zhao's version of events clashes significantly with the one provided in "The Tiananmen Papers," a collection of party documents published in 2001 that is considered the most definitive previous account of the crackdown. "The Tiananmen Papers" reported that there was a split vote of 2 to 2, with one abstention, and that retired Communist Party leaders were called in to decide.

Zhao's contention is that because there was no vote, the crackdown was illegal, even by the party's own rules. And once again, he notes, the hard-liners around Li Peng miscalculated. The martial law declaration prompted even bigger protests.

"A more intense confrontation was made inevitable," Zhao says. "On the night of June 3rd while sitting in the courtyard with my family, I heard intense gunfire. A tragedy to shock the world had not been averted, and was happening after all."

http://news.bbc.co.uk/chinese/simp/hi/newsid_8050000/newsid_8050500/8050596.stm

BBC: 赵紫阳秘密回忆录出版内情

美国西蒙舒斯特出版社本月将出版根据已故中国共产党前总书记赵紫阳独白口述录音翻译成的回忆录。总长近30个小时的录音带是赵紫阳在15年软禁期间独白录制的,在他去世后被三位朋友秘密带出中国。

赵紫阳因为在1989年支持天安门学生运动而遭罢官,随后被软禁在家,直到2005年去世。

赵紫阳最信任的秘书鲍彤在北京接受路透社采访时,亲耳听过这批录音带,认定说话者是赵紫阳。

鲍彤的儿子鲍朴和妻子花了四年时间把这些录音翻译成英文,使之出版。

这本回忆录的英文名字是《Prisoner of The State》,译成中文是《国家的囚犯》。

反思六四

赵紫阳在回忆录中反思六四天安门事件,形容那是一场悲剧。

赵紫阳回忆说,1989年6月3日夜里在家中花园里听到北京城密集的枪声时,他已经预料,一场震惊世界的悲剧将不可避免的发生。

赵紫阳在谴责军队镇压学生的同时说,他无论如何也不会担任指挥军队镇压学生的总书记。

推崇民主

在回忆录中赵紫阳还赞扬了西方的民主制度,认为中国应该循序渐进的迈向民主,中国共产党要严肃考虑民主化问题。

赵紫阳说,如果中国不朝西方的议会民主发展,不推动新闻自由,就无法解决腐败及贫富差距扩大的问题。

赵紫阳还回忆,他当时就说:"大部分人只是希望争取改正我们的缺点,而不是想推翻我们的政治制度。"

中英文出版

西蒙舒斯特出版社预定在六四事件20周年的前夕,出版这本长300页的回忆录。分中英文出版。

最初的计划是于5月19日在除了中国大陆之外的世界各地同时发行。

但香港的几家书店违反了发行规定,从四月份就开始出售赵紫阳的回忆录。

一些资深评论家已经在回忆录的前言和后记中作出评价,而赵紫阳当年的秘书鲍彤认为,这部回忆录将让中国共产党有更深的反思。

相 关报道

独 家报道:邓小平怎样改变了毛泽东?—《也谈改革30年》之六(鲍彤)

独 家报道:走出了死路一条没有?-《也谈改革30年》之五(鲍彤)

独 家报道:夭折•繁荣•赞美诗-《也谈改革30年》之四(鲍彤)

http://www.rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/ZZY-05142009093652.html

赵 紫阳: “六四”问题应当是非常清楚了

- 摘自录音回忆“改革历程(赵紫阳著)

2009-05-14

Photo:AFP

图 片:1989年六四镇压发生前夕,赵紫阳在天安门广场看望和劝说示威绝食的学生(1989年5月19日法新社)

赵 紫阳录音回忆(一)

下 载声音

赵 紫阳录音回忆(二)

下 载声音

6 月3日夜,我正同家人在院子里乘凉,听到街上有密集的枪声。一场举世震惊的悲剧终于未能避免地发生了。

“六 四”悲剧三年后,我记下了这些材料,这场悲剧已经过去好多年了。这场风波的积极分子,除少数人逃出国外,大部分人被抓,被判,被反覆审问。情况现在应当是 非常清楚了,应该说以下三个问题可以回答了:

第 一,当时说学潮是一场有领导,有计划,有预谋的“反党反社会主义”的政治斗争。现在可以问一下,究竟是什么人在领导?如何计划,如何预谋的?有哪些材料能 够说明这一点?还说党内有黑手,黑手是谁呀?

第 二,说这场动乱的目的是要颠覆共和国,推翻共产党,这方面又有什么材料?我当时就说过,多数人是要我们改正错误,而不是要根本上推翻我们的制度。这么多年 过去了,审讯中得到什么材料?究竟是我说得对还是他们说得对?许多外出的民运分子都说,他们在“六四”前,还是希望党往好处改变。 “六四“以后,党使他们完全绝望,使他们和党处在对立的方面。在学潮期间,学生提出过很多口号,要求,但就是没有提物价问题,而当时物价问题是社会上很大 的热点,是很容易引起共鸣的。学生们要和共产党作对,这么敏感的问题他们为什么不利用呢?提这样的问题不是更能动员群众吗?学生不提物价问题,可见学生们 知道物价问题涉及改革,如果直接提出物价问题动员群众,实际上要反对,否定改革。可见不是这种情况。

第 三,将“六四”定性为反革命暴乱,能不能站得住脚?学生一直是守秩序的,不少材料说明,在解放军遭到围攻时,许多地方反而是学生来保护解放军。大量市民阻 拦解放军进城,究竟是为了什么?是要推翻共和国吗?当然,那么多人的行动,总有极少数人混在人群里面攻打解放军,但那是一种混乱情况。北京市不少流氓,流 窜犯乘机闹事,那是完全可能的。难道能把这些行为说成是广大市民,学生的行为吗?这个问题到现在应当很清楚了。

以 上几点,就是说明1987年中央领导班子改组,耀邦辞职以后,面临着一个声势浩大的反自由化运动。在这种情况下,不反是不可能的。当时有一种很大的力量, 要乘反自由化来大肆批判三中全会的路线,要否定改革开放政策。而我如何顶住这股势力,如何把反自由化控制起来。不使扩大化,不涉及经济领域;尽量缩小范 围,尽量减少一些思想混乱,这是一个方面。再一个方面就是对人的处理的问题。要不要处理人,伤害人。如何少处理人,不过多伤害人,这也是我当时面对最头痛 的问题。

反 自由化以来,一些老人们劲头很大,极左势力也很大,想要整很多人。邓小平一向主张对党内一些搞自由化的人作出严肃处理。王震等其他几位老人也是如此。邓力 群,胡乔木等人更是想乘机把这些人置于死地而后快。在这种情况下,如何在这次反自由化中尽量少伤害一些人,保护一些人,即使没法避免也力求伤害得轻一些, 这是一件比较麻烦的事情。一开始,在制定中央四号文件时,为了少伤害一些人,对如何处理在反自由化中犯错误的人作出了严格的规定。文件提出:需要在报刊上 点名批判和组织处理的,只是个别公开鼓吹资产阶级自由化,屡教不改而影响很大的党员,并且应经中央批准。还指出,对有些持系统错误观点的人,可以在党的生 活会上进行同志式的批评,允许保留意见,采取和缓的方式。我在宣传部长会议上和其他场合还讲了在思想文化领域要团结绝大多数人的问题,指出包括有这样或那 样片面错误观点的人都要团结。我还指出,在从事思想理论文化领域工作的党员中,既鲜明坚持四项基本原则,又热心改革开放的人固然不少,但也有些人拥护四项 基本原则,而有些保守僵化,也有些人热心改革开放,而讲了些过头的话,出格的话。既不要把前者看成是教条主义,也不要把后者看成是自由化分子,都是要教育 团结的人。我当时有意识地强调反自由化时把有点自由化错误的人和有点僵化保守的人,都说成属于认识上的片面性,就是为了尽量避免或少伤害人。

但 是,我们已经实行了三十多年的社会主义,对一直遵循传统社会主义原则的中国人民,究竟应该给个什么说法呢?一种说法是,中国社会主义搞早了,该退回去, 重搞新民主主义;一种说法是,中国未经资本主义发展就搞社会主义,现在应当进行资本主义补课。这两种说法虽然不能说没有道理,但是必然会在理论上引起很大 争论,很可能在思想上造成新的混乱。特别是这样的提法不可能得到通过,搞得不好会使改革开放事业遭到夭折,因此不能采取。我在1987年春季考虑十三大报 告时,很长一个时期就考虑这个问题如何回答。在思考过程中我越来越觉得“社会主义初级阶段”这个提法最好。它既承认,肯定了我们已搞了几十年的社会主义的 历史,同时由于它是个初级阶段,完全可以不受所谓传统社会主义原则的约束,可以大胆地调整超越历史的生产关系,从越位的地方退回去,实行适合我国社会经济 水平和生产力发展需要的各种改革政策。

也 许有人会问,你过去在地方工作,怎么对经济改革发生兴趣?我认为中国经济必须改革,虽然那时我也看过一些东欧经济改革的书,但出发点不是为了改革而改 革,主要的是我认为中国的经济弊端太多,人民付出的代价太大,效益太差。但弊端的根本在哪里,开始也不是很清楚。总的想法就是要提高效益。来北京后,我对 经济工作的指导思想,明确地不是为了追求产值多少,也不是要把经济发展搞得多快,就是要在中国找到一个如何解决人们付出了劳动,而能得到相应的实惠的办 法,这就是我的出发点。资本主义发达国家经济增长2-3 %就不得了了,而我们经常增长10 % ,但人民生活没有得到改善。至于怎样找到一条路子,我当时观念里没有什么模式,没有系统的主张。我就是希望经济效益好,有这一条很重要。出发点就是经济效 益好,人民得到实惠。为了这个目的,摸索来,摸索去,最后就找到了适合我们的办法,逐渐走出了一条路。

当 然将来哪一天也许会出现比议会民主制更好,更高级的政治制度,但那是将来的事情,现在还没有。基于这一点就可以说,一个国家要实现现代化,不仅要实行市场 经济,发展现代的文明,还必须实行议会民主制这种政治制度。不然的话,这个国家就不可能使它的市场经济成为健康的,现代化的市场经济,也不可能实现现代的 法治社会。就会象许多发展中国家,包括中国出现权力市场化,社会腐败成风,社会两极分化严重的情况。

现 在回想起来,中国实行改革开放实在不容易,阻力很大,顾虑很多,很多无名恐惧,给要做这些事的人带了很多帽子。改革开放,尤其是开放很不容易。一涉及到与 外国人的关系,总怕丧权辱国,怕自己吃亏,说“肥水不流外人田” 。所以我常给他们讲这个道理:外国人到中国投资,他们本来就很多顾虑,我们的政策这样不稳定,应该说有很多风险,要怕的应该是拿钱进来的外商,我们中国政 府有什么可怕的呢?

http://www.rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/baotong1-05142009090724.html

鲍彤:赵紫阳录音回忆的历史背景(一)-中国为 什么非改革不可

2009-05-14赵紫阳留下了一套录音带。这是他的遗言。

赵紫阳的遗言属于全体中国人。以文字形式公之于世是我的主张,事情由我主持,我对此负政治上的责任。

赵紫阳录音回忆的价值,供世人公论。它的内容关系到一段正在继续影响着中国人现实命运的历史。这段历史的主题是改革。在大陆,在目前,这段历史是被封锁和 歪曲的对象。谈谈这一段历史的背景,也许对年轻的读者了解本书会有点用处。

* * *

“辛亥革命”以降,近百年来,尽管步履艰难,中国毕竟在朝着现代化的方向,缓慢地演变着,发展着。日本军国主义的侵略,阻碍了它的进程,却无法逆转它的方 向。

1949年内战基本结束后的中国,有了新的契机。

本来,如何循序渐进,如何实现现代化,要不要搞社会主义,都应该属于可以讨论,可以争论的范围。只要真的按照1949年9月29日中国人民政治协商会议第 一届全体会议制定的“共同纲领“去做,真的实现”普选“和”耕者有其田,也就很可以了。真把这两个大问题解决了,中国社会制度方面的其他一些问题,都不难 解决。

全面逆转中国发展方向的,是1953至1958年年以“社会主义改造”为名和1957年以“反右派”为名的两个运动。二者相辅相成。前者是针对所有制的, 是模仿“联共党史“第11章和第12章的模式,决定通过集体化,国有化,计划化,达到消灭私有制和市场经济的目的。后者是中共根据毛泽东的意志,由中共中 央整风反右领导小组组长邓小平指挥,在全国五百万名知识分子中,打出了五十五万“右派分子。 ”这两个运动是中共执政历史上的转捩点,开辟了与民主与法制背道而驰之路。

走上了这条自称为“社会主义”的路,就消灭了市场,消灭了“耕者有其田,也消灭了自由,同时也断送了中华民族代代相传的许多好的传统。面对建设,这种“社 会主义”乏善可陈,只能把老百姓维持在“少数人饿死,多数人饿而不死”的水平上。在毛泽东时代,有了城市户口,才能拥有凭证消费的保障,比如上海和北京的 居民,凭证消费的限额大约是每天将近一斤粮,三天大约能吃一两肉,每年大约能买做一套衣服的布;对占总人口百分之八十的农村居民,包括被迫“ 自愿”上山下乡的知识青年,党和国家爱莫能助,大家只能“自力更生”自生自灭。

毛泽东时代的“社会主义”使得中国人不仅人人贫困,而且同一百多年以来实现现代化的梦想背道而驰,越离越远。

毛泽东身后,他亲自指定的接班人党的主席华国锋不得不如实宣布, “国民经济濒于崩溃的边缘。长此以往,国将不国,这就是中国非改革不可的背景。

http://www.rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/baotong2-05142009091300.html

鲍彤:赵紫阳录音回忆的历史背景(二)-党国领 导当时开的药方里没有改革

2009-05-14出路何在?毛的前贴身警卫,党的副主席的汪东兴说,凡是毛主席的决定,必须永远执行,始终不渝。党主席华国锋也跟着他如是说。

当时的中国共产党内,威信最高的经济权威,是陈云。他三十年代就进入政治局,比邓小平早了二十多年。他在延安就开始管经济。毛发动“大跃进”之前,陈是第 一副总理,全国的经济总管。毛嫌他太实事求是,叫他靠边站。毛宣布自己是主帅,任命邓小平为副帅,大炼钢铁,结果闯了祸。现在毛死了,陈云给中国经济开出 来的药方是“调整”纠正比例失调。

这是陈云实践经验的结晶。大跃进“饿死了几千万农民, 1962年就是靠陈云”调整“粮食,钢铁等生产指标,才得以收拾残局。陈云反对党的瞎指挥,但不反对党的领导。从政治上的一党领导,到经济上的全盘公有化 计划化,粮棉油的统购统销,陈云不但不反对,而且都是他自己辛辛苦苦建立起来的制度。改掉毛的这一套,等于改掉陈云自己。

对陈云的分析不能简单化。他捍卫国有制,但不捍卫人民公社,他喜欢计划经济,但不喜欢不切实际的指标,他主张政府为主,但允许市场为辅(大集体,小自由“ ) ;他认为经济自由度应该像关在笼子里的”鸟“ ,但反对把它捏在手里,他相信苏联老大哥,不相信西方帝国主义;在”自力更生“ , ”不吃进口粮“那个年代,他敢于挺身作证”我听得毛主席说过,粮食是可以进口的,一句话,就把“进口粮”的修正主义性质,平反为毛泽东思想的合理要求;他 维护共产党的一元化领导,但对毛泽东破坏党规党法看不惯。这些,赵紫阳在回忆中都有记载,还历史以公道。

另一位威望极高的元老,是邓小平。邓是毛的亲信。因为毛指定刘少奇为唯一接班人,邓在文革前才当了刘的助手。文革初,不了解底细的群众把邓和刘误为一谈, 但毛心里明白,没有拿邓跟刘一样,往死里打。毛晚年企图整肃周恩来,邓却和周走到一起,这下子才失掉了毛的宠信。文革中邓一再被贬黜“越批越香,这不是降 低了而是提高了他在人们心目中的形象。 -也许,邓小平能够成为改革毛泽东体制的领导人?

但邓小平当时开出来的药方,也不是改革,而是“整顿。整顿,就是整顿企业,整顿领导班子,撤换不服从领导的干部,以铁腕落实既定的规章制度和组织纪律,以 铁腕完成和超额完成国家计划。简言之,不是改掉而是强化毛的体制。整顿是邓小平的强项。文革后期,毛主席叫“四人帮”抓革命,叫邓小平抓生产,邓虽然不懂 经济,但用了“整顿”的手段,硬是把生产搞上去了。

邓小平的特长是精明。他不糊涂,不迂阔。他心里早就明白,社会主义计划经济那一套也许无法挽救经济的崩溃,也许必须转而向市场经济求救。但他自己不能冒 “搞乱经济“的风险,更不能冒”反社会主义“的风险。毕竟,经济不是他的所长,他是搞政治的,必须在政治上站稳脚跟。 1979年3月,他发表了被载入史册的讲话“坚持四项基本原则:坚持社会主义道路,无产阶级专政,共产党的领导,马列毛的思想。这就是他的政治路线。一年 后,他以全党领袖的气魄,发表了进一步笼罩八十年代的纲领“目前的形势和任务,他指点江山,讲国际,讲台湾,重点是讲现代化建设。怎么现代化呢?读一读” 邓小平文选“第二卷中那篇洋洋三十四页的大文章就清楚了。邓小平开的是四味药:一,多快好省;二,安定团结;三,艰苦奋斗;四,又红又专。面对毛泽东死后 扔下的烂摊子,邓小平尽了一个政工人员的努力,他在加强领导,他在鼓舞士气,但是直到1980年的年1月,他的八十年代的纲领里没有体制改革。

后来的历史证明,改革就是改掉毛泽东的体制。不改革就只能在毛的体制里翻跟斗,不改革是死路一条。但当时的党国领导人,从华国锋,汪东兴到陈云,邓小平, 在他们当时开出来的药方里,都没有改革。

http://www.rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/baotong3-05142009091851.html

鲍彤:赵紫阳录音回忆的历史背景(三) - 四川在探寻改革之路

2009-05-14探寻体制改革之路,怎么改,是很重要的。更重要的是,到底改什么。

包括邓小平和陈云在内,当时谁都说不清楚什么叫做“体制改革。 ”在四川进行经济体制改革试点之前,中央领导人中没有人说得清楚(或者不愿意说清楚)体制改革“应该改掉什么,说来说去,无非“集中还是分散,分散还是集 中。这里有个风险的问题。

但是,四川想清楚了。不仅说了,而且动手了,稳稳当当开始做起来了。 1976年,四川开始放宽政策。 1978年起,由政策领域扩展到体制领域,进行了城乡经济体制改革试点。农村经济体制改革的内容,是扩大农民自主权;城市经济体制改革的内容,是扩大企业 自主权。自主权,不像“领导权,所有权,计划权”那样耀眼刺耳,但也不像“积极性”那样软不足道。你要“积极性,给你几块钱奖金,就足以把你打发掉了。你 说: ”所有权,计划权“自居正统的人非告你离经叛道不可。难道你不懂得“所有权”只姓“公” , “计划权”只姓“国” , “领导权”只姓“党”吗?但“自主权”不硬不软,明确,稳当,从这里入手,可以解剖得很深入,也能够把阵地守得很稳当。提出“农民自主权”和“企业自主权 ” ,有个不言而喻的前提-把“农民”和“企业” (而不再是“党”和“国家” )定位为城乡经济的主体。这也正是市场经济的前提。扩大“农民”和“企业”的自主权,和缩小“党”和“政府”的干预权,是百分之百的同义语。

1978年,四川省委在第一书记赵紫阳主持下,作出了以扩大自主权为内容进行改革试点的决策。这是使改革进入经济生活的实质性的一步,也是赵紫阳走上改革 之路的起点。作为改革家,他的使命就是推动党和国家向农民和企业让步,说得明白一点,就是推动“经济外的行政强制因素”向“经济的主体”让步。当时胡耀邦 在平反的实践中创造了“冤假错案”等一组辞汇,赵紫阳也在让步的实践中创造了“松绑,放权,让利,搞活”等一组辞汇,这些都是不见经传但不胫而走的历史性 概念,令人沉思,令人回味。

四川人口全国第一,川北,川南,川西,川东,包括现在的重庆直辖市,包括民国时代的西康全省,都在其内,当时全国十亿人,四川占了一亿。两千年自流灌溉的 历史,使四川成为天府之国。六十年代毛泽东把这里确定为三线建设的大后方,使它成为高精尖军事工业的大基地。大跃进“时期的四川省委第一书记,是个看毛眼 色行事,不顾百姓死活的人。 1959年至1961年年全国饿死三千万到四千万人,其中四川就死掉一千万!毛的体制把四川整苦了,扩大农民和企业自主权使四川获得新生。这当然不是领导 者个人有回天之力,但无疑凝结着领导者的心血。 “要吃粮,找紫阳”的民谣,越出省界,传到北京。

四川省委第一书记赵紫阳稳稳当当搞经济改革,同中共中央组织部长胡耀邦大刀阔斧平反冤假错案,成为当时街谈巷议中的两个亮点。

http://www.rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/baotong4-05142009092144.html

鲍彤:赵紫阳录音回忆的历史背景(四) - 进入了改革年代

2009-05-141978年和1979年,胡耀邦,赵紫阳相继进入政治局。 1980年的年2月,二人同时进入常委,胡任总书记,赵任中央财经小组组长,副总理(代总理)总理。

这就进入了赵紫阳回忆中的改革年代。同赵后来主持的全国规模的经济改革相比,他此前主持的四川改革只是小试牛刀而已。

体制改革,怎么改,谁说得清楚?说得清楚的人,五十年代以来,早就被斗光了。因为毛泽东已经用了几十年时间,致力于一场接一场的以摧毁市场经济为目标的 “阶级斗争,培养了一批又一批的以讨伐市场为能事的干部和学者,在全民中散布对市场经济的恐惧和仇恨。

现在又过了三十多年,终于人人恍然大悟:中国的改革,原来就是改掉毛泽东的制度。但在大陆,却有点怪,只许说改革,不许说非毛化。改革必须歌颂,非毛化必 须声讨。三十年后的今天尚且如此,三十年前如果有人提议要改掉毛的体制,无疑会遭到女教师张志新和女学生林昭同样的命运,改革则将命中注定要被彻底扼杀在 萌发之前。

对毛泽东经济体制的否定之路,也就是说,经济上的非毛化之路,是一步一步走出来的。 1978年是“自主权” 。

三年后, 1981年11月,赵紫阳提出了一个新的视角“经济效益。 ”他列举1952年到1980年的二十八年经济增长的成绩:工农业总产值8.1倍, 4.2倍国民收入,工业固定资产26倍。那么,全国人民的平均消费水平呢?一倍!走了二十八年的老路子,经济效益如此如此,今后不走新路子行吗!又过了三 年, 1984年, “商品经济”的概念,在赵紫阳等人苦心推动下,终于在中国站住了,终于合法了! “商品经济”是当时政治形势下所能允许合法使用的概念,实际上就是“市场经济”的代名词。

这就关系到改革的全过程,其中的甘苦与探索,合作与分歧,在本书中都有论述,这是我看到过的迄今最深入和最可靠的史料。

http://www.rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/baotong5-05142009092448.html

鲍彤:赵紫阳录音回忆的历史背景(五) - 赵与邓的分歧在于党和人民关系的定位上

2009-05-141989年,邓小平与赵紫阳之间发生了正面冲突。

胡耀邦之死触发了学潮。邓主张调集国防军镇压;赵主张在民主与法制的轨道上解决老百姓最关心的腐败问题和民主问题,在深化经济改革的同时启动政治体制改 革,引导全社会把注意力集中到改革上来。

结局是大家所已经看到了的:军委主席邓小平判决总书记赵紫阳犯了“分裂党”和“支持动乱”的罪行;元老们决定由江泽民取代赵。江上台后,把赵作为国家公敌 软禁终身,并且从国内的书报,新闻乃至历史中刮掉了赵紫阳的名字。

邓小平与赵紫阳之间不存在什么个人恩怨。 1980年年4月赵到北京工作,直到1989年4月学潮之前,邓小平对赵紫阳的工作是满意的,不是一般的满意,而是很满意。

邓小平最初对经济改革没有表态,那是因为没有把握,怕出了乱子,收拾不了局面。作为政治家,这很正常。看到四川的实绩以后,邓小平开始放心。看到赵到中央 后继续稳稳当当,用稳健的改革,来推动计划内和计划外各种经济成分同时稳定增长,邓更加放心了。可以说,对赵紫阳部署的经济改革,邓是言听计从的支持者, 没有保留的支持者,最有力量的支持者。对邓的支持,赵也由衷感到高兴。两个人合作得很好。

问题完全出在对1989年学潮的性质的判断上和决策的分歧上,深层的分歧发生在对党和人民关系的定位上。赵认为,学生悼念胡耀邦,是合法的,正常的。邓 说,这是反党反社会主义的动乱。赵说,学生提出的要求,反对腐败,要求民主,应该在民主和法制的轨道上,通过社会各界协商对话,找出解决的方案,进一步推 进改革。邓说,不能向学生让步,应该调集军队,首都必须戒严。这是5月17日下午在中共中央政治局常委会上发生的争论。常委会五个人。赵紫阳和胡启立是一 种意见;李鹏和姚依林是另一种意见;乔石中立。在这种情况下,邓小平居然说,他同意“常委多数”的决定-就这样,邓小平拍板了。

十三届政治局通过的“常委议事规则”规定,遇到在重大问题上出现分歧,常委应该向政治局报告,提请政治局或中央全会作决定。(当时的政治局委员十七人,十 四人在北京,虽有三人在外地,半天也能到齐。)邓小平也许认为,他不是常委委员,不必遵守常委的规则,也许,他认为,这个问题不够重大,他有权拍板,事后 通知政治局追认一下,就行了,也许,在他心目中,根本没有“规则”的观念。

“宪法”规定,中华人民共和国一切权力属于人民。邓小平也许认为,没有必要提请全国人民代表大会的常设机构表决,这种程式太麻烦,扯皮,效率低,办不成 事。也许,他压根儿认为,中华人民共和国宪法不是为“中国共产党的核心领导人”而设的。

“宪法”规定国务院有权决定戒严,但从5月17日常委决定戒严到5月19日实施戒严,这三天内,国务院到底有没有开过全体会议或常务会议,一查就清楚了。 我查过了,没有。

就这样,发生了几十万国防军进入首都,用坦克和冲锋枪对付学生和市民的“六四”屠城。国防军被用来对付向党和政府和平请愿的老百姓。惨绝人寰的大悲剧发生 了,接着又是全党全军全民大清查大迫害。稳定压倒一切,它压倒了改革,压倒了法律,压倒了良心,压倒了国家的主人,压得多少公民家破人亡!