What are the consequences of UD+ASSA?

Rolf Nelson

cosmological Measure Problem.)

Observational Consequences:

1. Provides a possible explanation for the "Measure Problem" of why we

shouldn't be "extremely surprised" to find we live in a lawful

universe, rather than an extremely chaotic universe, or a homogeneous

cloud of gas.

2. May help solve the Doomsday Argument in a finite universe, since

you probably have at least a little more "measure" than a typical

specific individual in the middle of a Galactic Empire, since you are

"easier to find" with a small search algorithm than someone surrounded

by enormous numbers of people.

3. For similar reasons, may help solve a variant of the Doomsday

Argument where the universe is infinite. This variant DA asks, "if

there's currently a Galactic Empire 10000 Hubble Volumes away with an

immensely large number of people, why wasn't I born there instead of

here?"

4. May help solve the Simulation Argument, again because a search

algorithm to find a particular simulation among all the adjacent

computations in a Galactic Empire is longer (and therefore, by UD

+ASSA, has less measure) than a search algorithm to find you.

5. In basic UD+ASSA (on a typical Turing Machine), there is a probably

a strict linear ordering corresponding to when the events at each

point in spacetime were calculated; I would argue that we should

expect to see evidence of this in our observations if basic UD+ASSA is

true. However, we do not see any total ordering in the physical

Universe; quite the reverse: we see a homogeneous, isotropic Universe.

This is evidence (but not proof) that either UD+ASSA is completely

wrong, or that if UD+ASSA is true, then it's run on something other

than a typical linear Turing Machine. (However, if you still want use

a different machine to solve the "Measure Problem", then feel free,

but you first need to show that your non-Turing-machine variant still

solves the "Measure Problem.")

Decision Theory Consequences (Including Moral Consequences):

Every decision algorithm that I've ever seen is prey to paradoxes

where the decision theory either crashes (fails to produce a

decision), or requires an agent to do things that are bizarre, self-

destructive, and evil. (If you like, substitute 'counter-intuitive'

for 'bizarre, self-destructive, and evil.') For example: UD+ASSA,

"Accepting the Simulation Argument", Utilitarianism without

discounting, and Utilitarianism with time and space discounting all

have places where they seem to fail.

UD+ASSA, like the Simulation Argument, has the following additional

problem: while some forms of Utilitarianism may only fail in

hypothetical future situations (by which point maybe we'll have come

up with a better theory), UD+ASSA seems to fail *right here and now*.

That is, UD+ASSA, like the Simulation Argument, seems to call on you

to do bizarre, self-destructive, and evil things today. An example

that Yudowsky gave: you might spend resources on constructing a unique

arrow pointing at yourself, in order to increase your measure by

making it easier for a search algorithm to find you.

Of course, I could solve the problem by deciding that I'd rather be

self-destructive and evil than be inconsistent; then I could consider

adopting UD+ASSA as a philosophy. But I think I'll pass on that

option. :-)

So, more work would have to be done the morality of UD+ASSA before any

variant of UD+ASSA can becomes a realistically palatable part of a

moral philosophy.

-Rolf

Bruno Marchal

Le 21-oct.-07, à 20:33, Rolf Nelson a écrit :

>

> (Warning: This post assumes an familiarity with UD+ASSA and with the

> cosmological Measure Problem.)

I am afraid you should say a little more on UD + ASSA. to make your

points below clearer. I guess by UD you mean UDist (the universal

distribution), but your remark remains a bit to fuzzy (at least for me)

to comment.

Of course I am not convinced by ASSA at the start, but still. The

absence of recation of ASSA defenders is perhaps a symptom that you are

not completely clear for them too?

Bruno

Wei Dai

> 1. Provides a possible explanation for the "Measure Problem" of why we

> shouldn't be "extremely surprised" to find we live in a lawful

> universe, rather than an extremely chaotic universe, or a homogeneous

> cloud of gas.

One thing I still don't understand, is in what sense exactly is the "Measure

Problem" a problem? Why isn't it good enough to say that everything exists,

therefore we (i.e. people living in a lawful universe) must exist, and

therefore we shouldn't be surprised that we exist. If the "Measure Problem"

is a problem, then why isn't there also an analogous "Lottery Problem" for

people who have won the lottery?

I admit that this "explanation" of why there is no problem doesn't seem

satisfactory, but I also haven't been able to satisfactorily verbalize what

is wrong with it.

> Of course, I could solve the problem by deciding that I'd rather be

> self-destructive and evil than be inconsistent; then I could consider

> adopting UD+ASSA as a philosophy. But I think I'll pass on that

> option. :-)

I think our positions are pretty close on this issue, except that I do

prefer to substitute 'counter-intuitive'. :-) The problem is, how can we be

so certain that our intuitions are correct?

> An example

> that Yudowsky gave: you might spend resources on constructing a unique

> arrow pointing at yourself, in order to increase your measure by

> making it easier for a search algorithm to find you.

While I no longer support UD+ASSA at this point (see my posts titled

"against UD+ASSA"), I'm not sure this particular example is especially

devastating. UD+ASSA perhaps implies an ethical theory in which all else

being equal, you would prefer that there was a unique, easy to find arrow

pointing at yourself. But it doesn't say that you should actually spend

resources constructing it, since those resources might be better used in

other ways, and it's not clear how much one's measure would actually be

increased by such an arrow.

Rolf Nelson

> Rolf Nelson wrote:

> > 1. Provides a possible explanation for the "Measure Problem" of why we

> > shouldn't be "extremely surprised" to find we live in a lawful

> > universe, rather than an extremely chaotic universe, or a homogeneous

> > cloud of gas.

>

> One thing I still don't understand, is in what sense exactly is the "Measure

> Problem" a problem? Why isn't it good enough to say that everything exists,

> therefore we (i.e. people living in a lawful universe) must exist, and

> therefore we shouldn't be surprised that we exist. If the "Measure Problem"

> is a problem, then why isn't there also an analogous "Lottery Problem" for

> people who have won the lottery?

I don't have anything novel to say on the topic, but maybe if I

restate the existing arguments, that'll help you expand on your

counter-argument.

The "Lottery Problem" would be a problem if I kept winning the lottery

every day; I'd think something was fishy, and search for an

explanation besides "blind chance", wouldn't you?

Let's rank some classes of people, from chaotic (many rules) to lawful

(few rules):

1. An infinite number of people live in "an infinite universe that

obeys the Standard Model until November 1, 2007, and then adopts

completely new laws of physics." If you live here, we predict that

strange things will happen on November 1.

2. An infinite number of people live next-door in "an infinite

universe that obeys the Standard Model through all of 2007, and maybe

beyond." If you live here, expect nothing strange.

3. An infinite number of people live across the street in "a universe

that looks like it obeys the Standard Model through November 1, 2007

because we are in the middle of a thermodynamic fluctuation, but the

universe itself is extremely lawful, to the point where it's just a

homogeneous gas with thermal fluctuations." We predict that strange

things will happen on November 1.

Your observations to date are consistent with all three models. What

are the odds that you live in (2) but not (1) or (3)? Surely the

answer is "extremely high", but how do we justify it *mathematically*

(and philosophically)? If we can find mathematical solutions to

satisfy this "Measure Problem", we can perhaps see what else that

mathematical solution predicts, and test its predictions. Your UD+ASSA

is the best solution I've seen so far, so I'm surprised there's not

more interest in UD+ASSA (or some variant) as a "proto-science".

>From the view of a potential scientific theory (rather than a

philosophical "formalization of induction"), it's a *good* thing that

it predicts "no oracles exist", because that is a falsifiable (though

weak) prediction.

Bruno Marchal

Le 25-oct.-07, à 03:25, Wei Dai a écrit :

>

> Rolf Nelson wrote:

>> 1. Provides a possible explanation for the "Measure Problem" of why we

>> shouldn't be "extremely surprised" to find we live in a lawful

>> universe, rather than an extremely chaotic universe, or a homogeneous

>> cloud of gas.

>

> One thing I still don't understand, is in what sense exactly is the

> "Measure

> Problem" a problem? Why isn't it good enough to say that everything

> exists,

> therefore we (i.e. people living in a lawful universe) must exist, and

> therefore we shouldn't be surprised that we exist. If the "Measure

> Problem"

> is a problem, then why isn't there also an analogous "Lottery Problem"

> for

> people who have won the lottery?

>

> I admit that this "explanation" of why there is no problem doesn't seem

> satisfactory, but I also haven't been able to satisfactorily verbalize

> what

> is wrong with it.

Perhaps there can be a measure problem with the ASSA, or not. I have no

idea because I think the ASSA idea, before having a measure problem,

has a reference class problem. We don't know what is the set or class

on which the measure can bear. If we say "observer", "observer-moment",

"observer-life" etc... we have to define observer first, and each time

this is done, it looks like I should be a bacteria instead of a human,

or the measure cannot be well defined, or it presuppose a "physical

world", etc. (see my old critics on ASSA, or on the Doomsday Argument.

Now, with the COMP (and thus the RSSA), things change.The reference

class is utterly well defined. For example, in the WM-duplication, it

is the set {W,M}. In front of the UD, the reference class, although it

is a non constructive object, it is, thanks to Church Thesis, a

perfectly well defined mathematical object: it is the set of all

states, going through your current state, generated by the DU. And the

measure problem is made equivalent with the white rabbits problem (due

to the existence of consistent but aberrant computations/histories (an

history, I recall, is a computation as viewed from a first person

perspective).

If you disagress with this, it means you stop somewhere in between the

first seven step of the 8-steps version of the UDA as in the slides

http://iridia.ulb.ac.be/~marchal/publications/SANE2004Slide.pdf

with explanations in

http://iridia.ulb.ac.be/~marchal/publications/SANE2004MARCHAL.htm

(html document), or

http://iridia.ulb.ac.be/~marchal/publications/SANE2004MARCHAL.pdf

(pdf document).

I would be interested to know where.

>

>> Of course, I could solve the problem by deciding that I'd rather be

>> self-destructive and evil than be inconsistent; then I could consider

>> adopting UD+ASSA as a philosophy. But I think I'll pass on that

>> option. :-)

>

> I think our positions are pretty close on this issue, except that I do

> prefer to substitute 'counter-intuitive'. :-) The problem is, how can

> we be

> so certain that our intuitions are correct?

>

>> An example

>> that Yudowsky gave: you might spend resources on constructing a unique

>> arrow pointing at yourself, in order to increase your measure by

>> making it easier for a search algorithm to find you.

>

> While I no longer support UD+ASSA at this point (see my posts titled

> "against UD+ASSA"), I'm not sure this particular example is especially

> devastating. UD+ASSA perhaps implies an ethical theory in which all

> else

> being equal, you would prefer that there was a unique, easy to find

> arrow

> pointing at yourself. But it doesn't say that you should actually spend

> resources constructing it, since those resources might be better used

> in

> other ways, and it's not clear how much one's measure would actually be

> increased by such an arrow.

I am not sure who "reads" that arrow, or even what *is* that arrow.

Bruno

Wei Dai

> Your observations to date are consistent with all three models. What

> are the odds that you live in (2) but not (1) or (3)? Surely the

> answer is "extremely high", but how do we justify it *mathematically*

> (and philosophically)?

My current position is, forget the "odds". Let's say there is no odds,

likelihood, probability, degrees of confidence, what have you, that I live

in (2) but not (1) or (3). Instead, I'll consider myself as living in all of

(1), (2), and (3), and whenever I make any decisions, I will consider the

consequences of my choices on all of these universes. But the end result is

that I'll still act *as if* I only live in (2) because I simply do not care

very much about the consequences of my actions in (1) and (3). I don't care

about (1) and (3) because those universes are too arbitrary or random, and I

can defend that by pointing to their high algorithmic complexities. So this

example does not seem to support the notion that the "Measure Problem" needs

to be solved.

> The "Lottery Problem" would be a problem if I kept winning the lottery

> every day; I'd think something was fishy, and search for an

> explanation besides "blind chance", wouldn't you?

If I kept winning the lottery every day, I would have the following

thoughts: There are two types of universe where I've won the lottery every

day, those where there's a reason I've won (e.g., it's rigged to always let

one person win) and those where there's no reason (i.e. I won them fair and

square). I am living in universes of both types, but I care much more about

those of the first type because they have lower algorithmic complexities.

Therefore I should act as if I'm living in the first type of universe and

try to find out what the reason is that I've won.

But what if I've won the lottery only once? I'd still be tempted to ask "why

did I win instead of someone else?" But the above rationale for searching

for an answer doesn't work, because there is no simpler universe where a

reason for my winning exists. The "Measure Problem" seems more like this

situation. In both cases, there is no apparent rationale for asking "why",

but we are tempted (or even compelled) to do so nevertheless.

Tom Caylor

How about SAI (Super Intelligence)? Or God? Seriously, of course.

The problem with generic SAI is the one you brought up: how do you

know the SAI is good? This problem does not exist with a good God.

Also the problem of what is the arrow, how do you make it, does not

exist with the Christian God, since the Christian God (and no other

one) made the arrow himself.

Tom

Bruno Marchal

Le 25-oct.-07, à 18:22, Tom Caylor a écrit :

> How about SAI (Super Intelligence)? Or God? Seriously, of course.

> The problem with generic SAI is the one you brought up: how do you

> know the SAI is good? This problem does not exist with a good God.

> Also the problem of what is the arrow, how do you make it, does not

> exist with the Christian God, since the Christian God (and no other

> one) made the arrow himself.

Hmmm.... It seems to me you are quite quick here.

Especially after reading Vance novels, as linked by Marc.

Is God good? Well, according to Plato, accepting the rather natural

"theological" interpretation of the Parmenides (like Plotinus), there

is a sense to say that God is "good", but probably not in the Christian

sense (if that can be made precise). Indeed, Plato's God is just Truth.

And Truth is not good as such, but the awareness of truth, or simply

the search of truth, is, for a Platonist, a prerequisite for the

*possible* development of goodness.

Truth is necessary for justice, and justice is necessary for goodness.

That's the idea. It makes knowledge (and thus truth) a good thing, in

principle.

But Vance's novel rises a doubt. Actually, that doubt can rise through

the reading of the first Pythagorean writings, which insist so much on

hiding their knowledge to the non-initiated people, making them secret.

(according to the legend, their kill a disciple who dares to make

public the discovery of the irrationality of the square root of 2).

Maimonides also, in his "Guide for the perplexed" insists that

fundamental knowledge has to be reserved for the initiated or the elite

people.

Fundamentally I don't know. I know a lot of particular case where

knowledge can be bad. But this happens always in "human, too much

human" practical circumstances, like during war, illness, etc. (it is

not good that your enemies *knows* where are your missiles; it is not

good to tell a bad new to some old dying people, etc. But this never

concerns fundamental truth.

I guess it *is* a question of faith. Of course, something like complete

knowledge, would be bad, making life without any purpose (at least it

is natural to fear that), but in this case both lobianity, and well,

may be things like Christianity, remind us about our finiteness and

about the fact that complete knowledge is inconsistent (even for Gods,

but not for the Unnameable, making it above thinking (something

Plotinus understood, but I am not sure Christians, following here

Aristotle theology, take this seriously into account but then they do

have confuse temporal and spiritual power isn't it?).

Now, Tom, to come back to the present thread, i.e. Wei Dai's question

on the meaning of the measure problem with respect to the ASSA

philosophy, frankly I am not sure that saying that God is responsible

for the indexical "arrow" will put light. It looks a bit like closing

even the possibility of progressing, given that God can hardly be

invoked in any attempt to scientifically explains something (cf

"scientifically" means based on a clear and doubtable (if not

refutable) theory). So you would have to elaborate, but as we have

already discussed, to use God here would mean that you do have a

doubtable and clear theory of God. OK if you are using lobian theology

(which is cristal clear I think), but which cannot be related so easily

with any human religion without much work on both human and machine and

comp, etc. We would quickly been led to propositions far more

difficult, not to say controversial, than Wei Dai's original question.

Of course, here, those who take the primacy of a physical universe for

granted, somehow, makes the same mistake than those who take God or a

God for granted. Such moves hide the questions through incommunicable

(perhaps even false) "certitude".

Bruno

Rolf Nelson

separated from utilities. Is "how much you care about the consequences

of your actions" isomorphic to "odds", or is there some subtlety I'm

missing here?

One thing unclear is whether you're advocating "moral relativism", or

whether you simply want an "escape clause" in your formal decision

theory so that if you don't like what your decision theory tells you

to do, you can alter your decision theory on the spot on a case-by-

case basis.

Brent Meeker

...

>

> Is God good? Well, according to Plato, accepting the rather natural

> "theological" interpretation of the Parmenides (like Plotinus), there

> is a sense to say that God is "good", but probably not in the Christian

> sense (if that can be made precise). Indeed, Plato's God is just Truth.

> And Truth is not good as such, but the awareness of truth, or simply

> the search of truth, is, for a Platonist, a prerequisite for the

> *possible* development of goodness.

> Truth is necessary for justice, and justice is necessary for goodness.

> That's the idea. It makes knowledge (and thus truth) a good thing, in

> principle.

> But Vance's novel rises a doubt. Actually, that doubt can rise through

> the reading of the first Pythagorean writings, which insist so much on

> hiding their knowledge to the non-initiated people, making them secret.

> (according to the legend, their kill a disciple who dares to make

> public the discovery of the irrationality of the square root of 2).

> Maimonides also, in his "Guide for the perplexed" insists that

> fundamental knowledge has to be reserved for the initiated or the elite

> people.

>

> Fundamentally I don't know. I know a lot of particular case where

> knowledge can be bad. But this happens always in "human, too much

> human" practical circumstances, like during war, illness, etc. (it is

> not good that your enemies *knows* where are your missiles; it is not

> good to tell a bad new to some old dying people, etc. But this never

> concerns fundamental truth.

But what truth is "fundamental"? Quantum gravity seems like an esoteric game to most people and so you can say anything you want about it without any ethical implications. But when quantum gravity seems to provide a non-supernatural cosmogony, religions are threatened and suddenly it's like bad news to a dying man (and we're all dying).

Coincidentally, James Watson has just lost his job because he said some things that, while narrowly true, support a racist view of Africa. Were they "fundamental" or does "fundamental" = "of no import in society"?

Brent Meeker

Wei Dai

> In standard decision theory, "odds" (subjective probabilities) are

> separated from utilities. Is "how much you care about the consequences

> of your actions" isomorphic to "odds", or is there some subtlety I'm

> missing here?

Your question shows that someone finally understand what I've been trying to

say, I think.

"how much you care about the consequences of your actions" is almost

isomorphic to "odds", except that I've found a couple of cases where

thinking in terms of the former works (i.e. delivers intuitive results)

whereas the latter doesn't. The first I described in "against UD+ASSA, part

1" at

http://groups.google.com/group/everything-list/browse_frm/thread/dd21cbec7063215b.

The second one is, what if your preferences for two universes are not

independent? For example, suppose you have the following preferences, from

most preferred to least preferred:

1) eat an apple in universe A and eat an orange in universe B

2) eat an orange in universe A and eat an apple in universe B

3) eat an apple in both universes

4) eat an orange in both universes

I don't see why this kind of preference must be irrational if you believe

that both A and B exists. But in standard decision theory, this kind of

preference is not allowed.

To put it more generally, thinking in terms of "how much you care about the

consequences of your actions" *allows* you to have an overall preference

about A and B that can be expressed as an expected utility:

P(A) * U(A) + P(B) * U(B)

since P(A) and P(B) can denote how much you care about universes A and B,

but it doesn't *force* you to have a preference of this form. Standard

decision theory does force you to.

> One thing unclear is whether you're advocating "moral relativism", or

> whether you simply want an "escape clause" in your formal decision

> theory so that if you don't like what your decision theory tells you

> to do, you can alter your decision theory on the spot on a case-by-

> case basis.

That's a very good question. I think if someone were to show me an objective

decision procedure that actually makes sense, I think I would give up "moral

relativism". But in the mean time, I don't see how to avoid these

counterintuitive implications without it.

Rolf Nelson

similar problems. If your two examples were the only problems that

UDASSA had, I would have few qualms about adopting it over the other

decision models I've seen. Note that even if you adopt a decision

model, you still in practice (as a human being) can keep an all-

purpose "escape hatch" where you can go against your formal model if

there are edge cases where you dislike its results.

In other words, I would prioritize "UDASSA doesn't yet make many

falsifiable predictions" and "We don't see a total ordering of points

in spacetime, so UDASSA probably doesn't run on a typical Turing

Machine" as larger problems. But sure, if UDASSA can be improved to

solve the morality edge-cases that you gave, I'm all for the

improvements.

As far as our observations of the Universe, I don't quite follow: how

can you go from "in terms of morality, probability is imperfect" to

"there's no such thing as probability, therefore there's no measure

problem?"

Rolf Nelson

> consequences of your actions" *allows* you to have an overall preference

> about A and B that can be expressed as an expected utility:

>

> P(A) * U(A) + P(B) * U(B)

>

> since P(A) and P(B) can denote how much you care about universes A and B,

> but it doesn't *force* you to have a preference of this form. Standard

> decision theory does force you to.

True. So how would an alternative scheme work, formally? Perhaps

utility can be formally based on the "Measure" of "Qualia" (observer

moments). If you have a halting oracle, certain knowledge of a

Universal Prior, and infinite cognitive resources, you can choose your

action to maximize a utility function U(X); X is the sequence M(Q1),

M(Q2), ..., where the measures of all possible Qualia are enumerated.

In the typical case of everyday life decisions in 2007, M would often

reduce to an objective probability oP; and U(X) = U(M(Q1), M(Q2), ...)

maybe has an affine (in other words, a decision-theory-order-

preserving) transformation, for a typical 2007 human, to some function

U(how good life is expected to be for earthly observer O1, how good

life is expected to be for earthly observer O2, ...), (pretending for

now that you don't have any way of altering the "total measure" taken

up by a human being.)

"How good life is expected to be for observer O1" in turn perhaps

reduces, in typical life, to oP(O1 experiences Q1) * (desirableness of

Q1) + oP(O1 experiences Q2) * (desirableness of Q2) + ...

But now we have to say that no one actually has infinite cognitive

resources, let alone a halting Oracle. So, we probably still want a

"logical probability" lP to deal with things like "To what extent do I

currently believe that the Riemann Hypothesis is true." So you can't

choose an action to maximize U directly, instead you want to maximize

the expected utility, by maximizing the following: lP(X1) * U(X1) +

lP(X2) * U(X2) + ...

Humans would perceive, as "subjective probability", a combination of

the Measure-based "objective probability" and the logic-based "logical

probability".

Clear as mud, I'm sure. Plus the odds are that I got something wrong

in the details. But that's my take on it, anyway.

Günther Greindl

> One thing I still don't understand, is in what sense exactly is the "Measure

> Problem" a problem? Why isn't it good enough to say that everything exists,

> therefore we (i.e. people living in a lawful universe) must exist, and

> therefore we shouldn't be surprised that we exist. If the "Measure Problem"

> is a problem, then why isn't there also an analogous "Lottery Problem" for

> people who have won the lottery?

thank you Wei Dei, I have expressed something similar concerning the

Doomsday Argument which has the same reasoning flaw.

You can't reason about probabilities "inside" the system and be

surprised that you are in "location" A or B.

Example:

1) If I draw from an urn with 1 Million white balls and 1 black ball, I

should be pretty surprised if I draw the black one.

2) If I am a black ball in an urn (same distribution as above) and I

only become conscious if I am drawn and I suddenly "wake up" to find

myself drawn, I shouldn't be surprised at all - my being drawn was a

condition for being a perceptive being.

I think a mixing up of these two viewpoints underly much of "measure

problem", doomsday and other arguments of the same sort.

Regards,

Günther

--

Günther Greindl

Department of Philosophy of Science

University of Vienna

guenther...@univie.ac.at

http://www.univie.ac.at/Wissenschaftstheorie/

Blog: http://dao.complexitystudies.org/

Site: http://www.complexitystudies.org

Brent Meeker

> Hi all,

>

>> One thing I still don't understand, is in what sense exactly is the "Measure

>> Problem" a problem? Why isn't it good enough to say that everything exists,

>> therefore we (i.e. people living in a lawful universe) must exist, and

>> therefore we shouldn't be surprised that we exist. If the "Measure Problem"

>> is a problem, then why isn't there also an analogous "Lottery Problem" for

>> people who have won the lottery?

That's a good argument assuming some laws of physics. But as I understood it, the "measure problem" was to explain the law-like evolution of the universe as a opposed to a chaotic/random/white-rabbit universe. Is it your interpretation that, among all possible worlds, somebody has to live in law-like ones; so it might as well be us?

Brent Meeker

Wei Dai

> Wei, your examples are convincing, although other decision models have

> similar problems. If your two examples were the only problems that

> UDASSA had, I would have few qualms about adopting it over the other

> decision models I've seen. Note that even if you adopt a decision

> model, you still in practice (as a human being) can keep an all-

> purpose "escape hatch" where you can go against your formal model if

> there are edge cases where you dislike its results.

For me, this line of thought started with the question "what does

probability mean if everything exists?" (Actually, before that I had thought

about "what does probability mean if brain copying is possible?") I've

entertained many different possible answers. I looked at decision theories

not because I'm looking for a decision procedure to adopt, but because that

is one way probability is interpreted and justified. I'm actually more

interested in the philosophical issues rather than the practical ones.

Besides, if you program a decision procedure into an AI, it had better be

flawless because there may be no "escape hatches".

> In other words, I would prioritize "UDASSA doesn't yet make many

> falsifiable predictions" and "We don't see a total ordering of points

> in spacetime, so UDASSA probably doesn't run on a typical Turing

> Machine" as larger problems. But sure, if UDASSA can be improved to

> solve the morality edge-cases that you gave, I'm all for the

> improvements.

I consider UD+ASSA to be a theory of how people reason, or how they ought to

reason, and as such, it does make falsifiable predictions. In fact, as I

showed in several examples, the predictions have been falsified.

About your comment "We don't see a total ordering of points in spacetime, so

UDASSA probably doesn't run on a typical Turing Machine". I don't follow

your reasoning here as to why UD+ASSA+typical TM implies that we should see

a total ordering of points in spacetime. Isn't it possible that such an

ordering exists internal to the TM's program, but it's not visible to the

people inside the universe that the TM simulates?

> As far as our observations of the Universe, I don't quite follow: how

> can you go from "in terms of morality, probability is imperfect" to

> "there's no such thing as probability, therefore there's no measure

> problem?"

My reasoning goes like this:

1. We need to reinterpret probability, from "subjective degree of belief" to

"how much do I care about something" in order to fix counterintuitive

implications of decision theory.

2. Once we do that, we no longer seem to have a solution to the "measure

problem".

3. Let's look closer at the nature of the problem. It seems to consist of

two parts:

(A) Why am I living in an apparently lawful universe?

(B) Why should I expect the future to continue to be lawful?

4. I think (B) is the easier question, and I answered it in a previous post

in this thread. (A) is more problematic, but my tentative answer is that, as

Brent Meeker stated it, "among all possible worlds, somebody has to live in

law-like ones; so it might as well be us."

I'm out of time today, and will respond to your other post tomorrow.

Wei Dai

> That's a good argument assuming some laws of physics. But as I understood

> it, the "measure problem" was to explain the law-like evolution of the

> universe as a opposed to a chaotic/random/white-rabbit universe. Is it

> your interpretation that, among all possible worlds, somebody has to live

> in law-like ones; so it might as well be us?

Yes. See my other post today.

Rolf Nelson

> I don't care

> about (1) and (3) because those universes are too arbitrary or random, and I

> can defend that by pointing to their high algorithmic complexities.

In (3) the universe doesn't have a high aIgorithmic complexity.

Any theory that just says "we only care about universes with low

algorithmic complexity" leads to (3) (assuming that, by "the

universe", you have the usual meaning of "that vast space we seem to

live in" rather than "my immediate perceptions".) The specific reason

I like UDASSA is because it gives you a framework for saying, "the

universe, plus my index in the universe, has a low algorithmic

complexity."

Rolf Nelson

> UDASSA probably doesn't run on a typical Turing Machine". I don't follow

> your reasoning here as to why UD+ASSA+typical TM implies that we should see

> a total ordering of points in spacetime. Isn't it possible that such an

> ordering exists internal to the TM's program, but it's not visible to the

> people inside the universe that the TM simulates?

It definitely is possible, my only point is that the fact that most

UTM program outputs don't have an easily-observed homogeneous and

isotropic n-dimensional space in their output, *may* be Bayesian

evidence against the plain UDASSA. So if we consider 3 hypotheses:

1. plain UDASSA

2. UDASSA variants, such as the set-theory UDASSA you mentioned, or a

UDASSA on a UTM that can atomically implement higher-level operations

like "multiply two complex numbers to infinite precision" and "apply

an operation uniformly to an infinite manifold".

3. something else

Then the lack of ordering that we see probably gives me a "Bayesian

Shift" from (1) to (2) or (3). However, to demonstrate would probably

be difficult, and if we had something powerful enough to do this, we

might have a theory that allows UDASSA to make novel predictions about

the observed Universe.

Rolf Nelson

> be difficult, and if we had something powerful enough to do this, we

> might have a theory that allows UDASSA to make novel predictions about

> the observed Universe.

To give examples of how hard this is:

1. What is the probability that our Universe has existed since the Big

Bang, but will abruptly end tomorrow? There have been about 2^16 days

since the Big Bang, so we can get a lower bound of probability in

UDASSA with 1 / 2^((length of a binary program that runs a Universe

for x subjective time, then halts) + (about 16 bits)). I don't know

how to program any of the basic TM's, and can't personally estimate of

the complexity of the first term. And this is just to get an lower

bound, the actual probability is probably much higher.

2. Take a real-world example, like the Pioneer Anomaly; does "new laws

of physics caused the Pioneer Anomaly" have a higher or lower

complexity than "there is a mundane explanation for the Pioneer

Anomaly"? Good luck!

On the plus side, one wouldn't have to solve every problem to make

UDASSA into a science; one would just have to solve (successfully

predict) a handful of novel problems (that aren't solvable by other

methods) to demonstrate that is true and useful.

Wei Dai

> On Oct 25, 7:59 am, "Wei Dai" <wei...@weidai.com> wrote:

>> I don't care

>> about (1) and (3) because those universes are too arbitrary or random,

>> and I

>> can defend that by pointing to their high algorithmic complexities.

>

> In (3) the universe doesn't have a high aIgorithmic complexity.

I should have said that in (3) our decisions don't have any consequences, so

we disregard them even if we do care what happens in them. The end result is

the same: I'll act as if I only live in (2).

From your post yesterday:

> True. So how would an alternative scheme work, formally? Perhaps

> utility can be formally based on the "Measure" of "Qualia" (observer

> moments).

This is one of the possibilities I had considered and rejected, because it

also leads to counterintuitive consequences. For example, suppose someone

gives your the following offer:

I will throw a fair coin. If the coin lands heads up, you will be

instantaneously vaporized. If it lands tails up, I will exactly double your

measure (say by creating a copy of your brain and continuously keeping it

synchronized).

Given your "measure of qualia"-based formalization of utility, and assuming

that you're selfish so that you're only interested in the measure of the

qualia of your own future selves, you'd have to be indifferent between

accepting this offer and not accepting it.

Instead, here's my current approach for a formalization of decision theory.

Let a set S be the description of an agent's knowledge of the multiverse.

For example, for a Tegmarkian version of the multiverse, elements of S have

the form (s, t) where s is a statement of second-order logic, and t is

either "true" or "false". For simplicity, assume that the decision-making

agent is logically omniscient, which means he knows the truth value of all

statements of second-order logic, except those that depend on his own

decisions. We'll say that he prefers choice A to choice B if and only if he

prefers S U C(E,A) to S U C(E,B), where U is the union operator, C(x,y) is

the logical consequences of everyone having qualia x deciding to do y, and E

consists of all of his own memories and observations.

In this most basic version, there is not even a notion of "how much one

cares about a universe". I'm relatively confident that it doesn't lead to

any counterintuitive implications, but that's mainly because it is too weak

to lead to any kind of implications at all. So how do we explain what

probability is, and why the concept has been so useful?

Well, let's consider an agent who happens to have preferences of a special

form. It so happens that for him, the multiverse can be divided into several

"regions", the descriptions of which will be denoted S_1, S_2, S_3, etc.,

such that S_1 U S_2 U S_3 ... = S and his preferences over the whole

multiverse can be expressed as a linear combination of his preferences over

those "regions". That means, there exists functions P(.) and U(.) such that

he prefers the multiverse S to the multiverse T if and only if

P(S_1)*U(S_1) + P(S_2)*U(S_2) + P(S_3)*U(S_3) + ...

> P(T_1)*U(T_1) + P(T_2)*U(T_2) + P(T_3)*U(T_3) ...

I haven't worked out all of the details of this formalism, but I hope you

can see where I'm going with this...

Bruno Marchal

How do the UDASSA, or the UDISTASSA, people take the difference

between first person and third person into account? Do they?

With the RSSA (through the use of the UD) it should be clear that THIRD

person determinism and computability entails FIRST person indeterminacy

and "observable non computability" (like what we can "see" when

preparing many particles in the state 1/sqrt(2)(up+down) and looking

them in the base {up, down}.

Bruno

Bruno Marchal

Le 26-oct.-07, à 20:18, Brent Meeker a écrit :

OK. I should not have talk about "fundamental truth", but about

"fundamental question". By which I mean "where do I come from?", "what

can we hope", "what is the nature of matter", "is life a dream?" etc.

None of those question are really addressed by today's science which

focuses on the physical aspect of reality without really tackling

seriously (in the doubting way) its metaphysical aspect and its psycho

or theo logical aspect.

> Quantum gravity seems like an esoteric game to most people and so you

> can say anything you want about it without any ethical implications.

> But when quantum gravity seems to provide a non-supernatural

> cosmogony, religions are threatened and suddenly it's like bad news to

> a dying man (and we're all dying).

If a religion is threatened by science, it means it is build on bad

faith. At least with comp science has to be a part of theology. If

theology does not extend science, it means it is wrong. Now sometimes

some scientist talk like if they were priest, and that is two times

more wrong than usual priest talk. Religion, like science, is

threatened by bad science, and even more by bad religion (religion

based on "blind" faith or authoritative argument).

Now, don't tell me that a theory like quantum gravity provides a non

supernatural cosmogony given that quantum gravity study quantum gravity

and perhaps the physical universe, but not the mind, nor the soul, the

person or consciousness. It is not its subject a priori. To look at

quantum gravity as a cosmogony is a confusion between subject like

physics and theology. This threatens theology, because without making

some very strong physicalist assumption, which are incompatible with

the mechanist thesis, it consists to make physics a religion without

saying! This is just dishonest. Such a physical universe is worst than

a white male God, because it looks scientific (unlike the male God),

but it isn't.

It looks that in winter, people forget all about the 1/3 distinction.

In Quantum gravity this 1/3 distinction is a bit hidden. You have to

postulate comp, and thus Everett before. (Well, as you know, you have

to derive Everett but it is not the point here).

>

> Coincidentally, James Watson has just lost his job because he said

> some things that, while narrowly true, support a racist view of

> Africa. Were they "fundamental" or does "fundamental" = "of no

> import in society"?

I love Watson because I discover "the math of computer science" by

myself in his book "Molecular Biology of the Gene". This book has

played a so big role in my youth that I have been using for years the

word "Watson" as a synonym of "Bible".

But J. Watson has become the worst materialist I have ever heard about.

According to a talk I have followed some years ago (I should search for

the reference) Watson seems to believe only in ATOMS". Someone told him

"Surely you believe in molecules M. Watson". And James Watson would

have answered: "No, I don't, there are only atoms!".

Weird ....

By "fundamental" I really mean the same as in "fundamental science".

Unless in company of theological hypothesis, it has no more impact on

society other than its technical products.

Einstein discovered the relation between matter and energy only through

a deep motivation for fundamental question: what is matter, what is the

nature of light, how could resemble the universe when seen by a

photon, etc.

But of course, its questioning led him to the discovery of precise and

refutable empirical statements, most of them did have incredible

impacts of our live today.

Bruno

Rolf Nelson

>

> I should have said that in (3) our decisions don't have any consequences, so

> we disregard them even if we do care what happens in them. The end result is

> the same: I'll act as if I only live in (2).

In the (3) I gave, you're indexed so that the thermal fluctuation

doesn't dissolve until November 1, so your actions still have

consequences.

> I will throw a fair coin. If the coin lands heads up, you will be

> instantaneously vaporized. If it lands tails up, I will exactly double your

> measure (say by creating a copy of your brain and continuously keeping it

> synchronized).

This is one of a larger class of problems related to volition, and the

coupling of my qualia to an external reality, that I don't currently

have an answer for. I want to live on in the current Universe, I don't

to die and have a duplicate of myself created in a different Universe.

I want to eat a real ice cream cone, I don't want you to stimulate my

neurons to make me imagine I'm eating an ice cream cone. I would argue

that a world where I can interact with real people is, in some sense,

better than a world where I interact with imaginary people who I

believe are real.

> Well, let's consider an agent who happens to have preferences of a special

> form. It so happens that for him, the multiverse can be divided into several

> "regions", the descriptions of which will be denoted S_1, S_2, S_3, etc.,

> such that S_1 U S_2 U S_3 ... = S and his preferences over the whole

> multiverse can be expressed as a linear combination of his preferences over

> those "regions". That means, there exists functions P(.) and U(.) such that

> he prefers the multiverse S to the multiverse T if and only if

>

> P(S_1)*U(S_1) + P(S_2)*U(S_2) + P(S_3)*U(S_3) + ...

>

> > P(T_1)*U(T_1) + P(T_2)*U(T_2) + P(T_3)*U(T_3) ...

>

> I haven't worked out all of the details of this formalism, but I hope you

> can see where I'm going with this...

You have a general model, which can encompass classical decision

theory, but can also encompass other models as well. It's not

immediately clear to me what benefit, if any, we get from such a

general model.

Wei Dai

> In the (3) I gave, you're indexed so that the thermal fluctuation

> doesn't dissolve until November 1, so your actions still have

> consequences.

Still not a problem: the space-time region that I can affect in (3) is too

small (i.e., its measure is too small, complexity too large) for me to care

much about the consequences of my actions on it.

> This is one of a larger class of problems related to volition, and the

> coupling of my qualia to an external reality, that I don't currently

> have an answer for. I want to live on in the current Universe, I don't

> to die and have a duplicate of myself created in a different Universe.

> I want to eat a real ice cream cone, I don't want you to stimulate my

> neurons to make me imagine I'm eating an ice cream cone. I would argue

> that a world where I can interact with real people is, in some sense,

> better than a world where I interact with imaginary people who I

> believe are real.

To me, these examples show that we do not care just about qualia, but also

about attributes and features of the multiverse that can not be classified

as qualia, and therefore we should rule out decision theories that cannot

incorporate preferences over non-qualia.

> You have a general model, which can encompass classical decision

> theory, but can also encompass other models as well. It's not

> immediately clear to me what benefit, if any, we get from such a

> general model.

Fair question. I'll summarize:

1. We are forced into considering such a general model because we don't have

a more specific one that doesn't lead to counterintuitive implications.

2. It shows us what probabilities really are. For someone whose preferences

over the multiverse can be expressed as a linear combination of preferences

over regions of the multiverse, a probability function can be interpreted as

a representation of how much he cares about each region. I would argue that

most of us in fact have preferences of this form, at least approximately,

which explains why probability theory has been useful for us.

3. It gives us a useful framework for considering anthropic reasoning

problems such as the Doomsday Argument and the Simulation Argument. We can

now recast these questions into "Do we prefer a multiverse where people in

our situation act as if doom is near?" and "Do we prefer a multiverse where

people in our situation act as if they are in simulations?" I argue that its

easier for us to consider these questions in this form.

4. For someone on a practical mission to write an AI that makes sensible

decisions, perhaps the model can serve as a starting point and as

illustration of how far away we still are from that goal.

Brent Meeker

This seems to just reverse the decision theoretic meaning of probability. Usually one cares more about probables outcome and ignores the very improbable ones. For example I prefer a region in which I'm rich, handsome, and loved by all beautiful women - but I don't assign much probability to it.

>

> 3. It gives us a useful framework for considering anthropic reasoning

> problems such as the Doomsday Argument and the Simulation Argument. We can

> now recast these questions into "Do we prefer a multiverse where people in

> our situation act as if doom is near?" and "Do we prefer a multiverse where

> people in our situation act as if they are in simulations?" I argue that its

> easier for us to consider these questions in this form.

But it seems the answer might depend on whether the premise were true - which makes the problem harder.

Brent Meeker

marc....@gmail.com

On Oct 31, 3:28 pm, "Wei Dai" <wei...@weidai.com> wrote:

>

> 4. For someone on a practical mission to write an AI that makes sensible

> decisions, perhaps the model can serve as a starting point and as

> illustration of how far away we still are from that goal.

Heh. Yes, very interesting indeed. But a huge body of knowledge and

a great deal of smartness is needed to even begin to grasp all that

stuff ;)

As regards AI I gotta wonder whether that 'Decision Theory' stuff is

really 'the heart of the matter' - perhaps its the wrong level of

abstraction for the problem. That is it say, it would be great if the

AI could work out all the decision theory for itself, rather than

having us trying to program it in (and probably failing miserably).

Certainly, I'm sure as hell not smart enough to come up with a working

model of decisions. So, rather than trying to do the impossible,

better to search for a higher level of abstraction. Look for the

answers in communication theory/ontology, rather than decision

theory. Decision theory would be derivative of an effective ontology

- that saves me the bother of trying to work it out ;)

Brent Meeker

Decisions require some value structure. To get values from an ontology you'd have to get around the Naturalistic fallacy.

Brent Meeker

marc....@gmail.com

On Oct 31, 7:40 pm, Brent Meeker <meeke...@dslextreme.com> wrote:

>

> Decisions require some value structure. To get values from an ontology you'd have to get around the Naturalistic fallacy.

>

> Brent Meeker- Hide quoted text -

>

> - Show quoted text -

Decision theory has this same problem. Decision theory doesn't

require values. The preferences (values) are plugged in from outside

the theory. Decision theory is merely a way of computing the best way

to achieve the desired outcomes. It doesn't say what we should desire

though.

Decision theory is too hard for me and too complex. What I'm

suspecting is that it's not the final word. I'm looking for a higher

level theory capable of deriving the results in decision theory

indirectly without me having to directly work them out.

My suspicion currently focuses on communication theory, knowledge

representation and data modelling (ontology). Rather than 'getting

values out' I think values are most likely somehow implicitly built

into the structure of ontology itself.

George Levy

measure of a given observer? High measure corresponds to a small

universe and conversely, low measure to a large one. For the observer

the decrease in his measure would be caused by all the possible mode of

decay of all the nuclear particles necessary for his consciousness.

Corresponding to this decrease, the radius of the observable universe

increases to make the universe less likely.

This would provide an experimental way to measure absolute measure.

I am not a proponent of ASSA, rather I believe in RSSA and in a

cosmological principle for measure: that measure is independent of when

or where the observer makes an observation. However, I thought that

tying cosmic expansion to measure may be an interesting avenue of inquiry.

George Levy

Rolf Nelson wrote:

>(Warning: This post assumes an familiarity with UD+ASSA and with the

>cosmological Measure Problem.)

>

>Observational Consequences:

>

>1. Provides a possible explanation for the "Measure Problem" of why we

>shouldn't be "extremely surprised" to find we live in a lawful

>universe, rather than an extremely chaotic universe, or a homogeneous

>cloud of gas.

>

>2. May help solve the Doomsday Argument in a finite universe, since

>you probably have at least a little more "measure" than a typical

>specific individual in the middle of a Galactic Empire, since you are

>"easier to find" with a small search algorithm than someone surrounded

>by enormous numbers of people.

>

>3. For similar reasons, may help solve a variant of the Doomsday

>Argument where the universe is infinite. This variant DA asks, "if

>there's currently a Galactic Empire 10000 Hubble Volumes away with an

>immensely large number of people, why wasn't I born there instead of

>here?"

>

>4. May help solve the Simulation Argument, again because a search

>algorithm to find a particular simulation among all the adjacent

>computations in a Galactic Empire is longer (and therefore, by UD

>+ASSA, has less measure) than a search algorithm to find you.

>

>5. In basic UD+ASSA (on a typical Turing Machine), there is a probably

>a strict linear ordering corresponding to when the events at each

>point in spacetime were calculated; I would argue that we should

>expect to see evidence of this in our observations if basic UD+ASSA is

>true. However, we do not see any total ordering in the physical

>Universe; quite the reverse: we see a homogeneous, isotropic Universe.

>This is evidence (but not proof) that either UD+ASSA is completely

>wrong, or that if UD+ASSA is true, then it's run on something other

>than a typical linear Turing Machine. (However, if you still want use

>a different machine to solve the "Measure Problem", then feel free,

>but you first need to show that your non-Turing-machine variant still

>solves the "Measure Problem.")

>

>

>Decision Theory Consequences (Including Moral Consequences):

>

>Every decision algorithm that I've ever seen is prey to paradoxes

>where the decision theory either crashes (fails to produce a

>decision), or requires an agent to do things that are bizarre, self-

>destructive, and evil. (If you like, substitute 'counter-intuitive'

>for 'bizarre, self-destructive, and evil.') For example: UD+ASSA,

>"Accepting the Simulation Argument", Utilitarianism without

>discounting, and Utilitarianism with time and space discounting all

>have places where they seem to fail.

>

>UD+ASSA, like the Simulation Argument, has the following additional

>problem: while some forms of Utilitarianism may only fail in

>hypothetical future situations (by which point maybe we'll have come

>up with a better theory), UD+ASSA seems to fail *right here and now*.

>That is, UD+ASSA, like the Simulation Argument, seems to call on you

>to do bizarre, self-destructive, and evil things today. An example

>that Yudowsky gave: you might spend resources on constructing a unique

>arrow pointing at yourself, in order to increase your measure by

>making it easier for a search algorithm to find you.

>

>Of course, I could solve the problem by deciding that I'd rather be

>self-destructive and evil than be inconsistent; then I could consider

>adopting UD+ASSA as a philosophy. But I think I'll pass on that

>option. :-)

>

>So, more work would have to be done the morality of UD+ASSA before any

>variant of UD+ASSA can becomes a realistically palatable part of a

>moral philosophy.

>

>-Rolf

>

>

>>

>

>

>

>

Russell Standish

>

> Could we relate the expansion of the universe to the decrease in

> measure of a given observer? High measure corresponds to a small

> universe and conversely, low measure to a large one. For the observer

> the decrease in his measure would be caused by all the possible mode of

> decay of all the nuclear particles necessary for his consciousness.

> Corresponding to this decrease, the radius of the observable universe

> increases to make the universe less likely.

>

> This would provide an experimental way to measure absolute measure.

>

> I am not a proponent of ASSA, rather I believe in RSSA and in a

> cosmological principle for measure: that measure is independent of when

> or where the observer makes an observation. However, I thought that

> tying cosmic expansion to measure may be an interesting avenue of inquiry.

>

> George Levy

>

There is a relationship, though perhaps not quite what you think. The

measure of an OM will be 2^{-C_O}, where C_O is the amount of

information about the universe you know at that point in time

(measured in bits). The physical complexity C of the universe at a point

in time is in some sense the limit of all that is possible to know

about the universe, ie C_O <= C.

C is related to the size of the universe by the equation H = C + S,

where S is the entropy of the universe (measured in bits), and H is

the maximum possible entropy that would pertain if the universe were

in equilibrium. H is a monotonically increasing function of the size

of the universe - something like propertional to the volume (or

similar - I forget the details). S is also an increasing function (due

to the second law), but doesn't increase as fast as H. Consequently C

increases as a function of universe age, and so C_O can be larger now

than earlier in the universe, implying smaller OM measures.

However, it remains to be seen whether the anthropic reasons for

experiencing a universe 10^9 years and of large complexity we

currently see is necessary...

--

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

A/Prof Russell Standish Phone 0425 253119 (mobile)

Mathematics

UNSW SYDNEY 2052 hpc...@hpcoders.com.au

Australia http://www.hpcoders.com.au

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

John Mikes

So you want to supersede the Archimede-Einstein wisdom ('gimme a fixed point"...to: total relativity) - which is OK with me. I like the way you approach questions (big deal for you<G>).

Main topic: Reverse Hubble? do we go towards a ;Big Bang', which is indeed a slow fade-out into a zero-point? (a slow No-Bang, indeed).

I had questions about that expansionary idea, ingenious as it was. Brent did not like my skepticism, but I am no physicist and can take a physicist-put down.

I was missing the 'objective' (forgive me for this adjective) - all encompassing study to "exclude" ALL other possibilities for a redshift. (a topical impossibility). I had two little questions (never got answers):

1. do the 'atomic measures' (hypothetical as they may be) like distance "between" nucleus and electrons (calculational fairytale) also expand? or

2. does the physical story of today's intrinsic measures stay put and only the biggies expand?

In the first case nothing really happens, we just believe in a narrative.

So as much as I applaud your shrinking idea, it is still part of the narrative.

But it is a great idea. Thanks.

John M

George Levy

We are trying to related the expansion of the universe to decreasing measure. You have presented the interesting equation:

H = C + S

1) Recently an article appeared in New Scientist stating that we may be living "inside" a black hole, with the event horizon being located at the limit of what we can observe ie the radius of the current observable universe.

2) Stephen Hawking showed that the entropy of a black hole is proportional to its surface area.

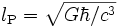

is the Planck

length.

is the Planck

length.Thus we can say that a change in the Universe's radius corresponds to a change in entropy dS. Therefore, dS/dt is proportional to dA/dt and to 8PR(dR/dt) R being the radius of the Universe and P = Pi. Let's assume that dR/dt = c

Therefore

dS/dt = (k/4 L^2) 8PRc = 2kPRc/ L^2

Since Hubble constant is 71 ± 4 (km/s)/Mpc

which gives a size of the Universe from the Earth to the edge of the visible universe. Thus R = 46.5 billion light-years in any direction; this is the comoving radius of the visible universe. (Not the same as the age of the Universe because of Relativity considerations)

Now I have trouble relating these facts to your equation H = C + S or maybe to the differential version dH = dC + dS. What do you think? Can we push this further?

George

Russell Standish

> Russel,

>

> We are trying to related the expansion of the universe to decreasing

> measure. You have presented the interesting equation:

>

> H = C + S

>

> Let's try to assign some numbers.

> 1) Recently an article

> hole, with the event horizon being located at the limit of what we can

> observe ie the radius of the current observable universe.

> 2) Stephen Hawking

>

>

> where where k is Boltzmann's constant

>

> Thus we can say that a change in the Universe's radius corresponds to a

> change in entropy dS. Therefore, dS/dt is proportional to dA/dt and to

> 8PR(dR/dt) R being the radius of the Universe and P = Pi. Let's assume

> that dR/dt = c

> Therefore

>

> dS/dt = (k/4 L^2) 8PRc = 2kPRc/ L^2

>

> 71 ą 4 (km <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kilometer>/s

> <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second>)/Mpc

> <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Megaparsec>

>

> which gives a size of the Universe

> direction; this is the comoving radius

>

> Now I have trouble relating these facts to your equation H = C + S or

> maybe to the differential version dH = dC + dS. What do you think? Can

> we push this further?

>

> George

>

I think that the formula you have above for S_{BH} is the value that

should be taken for the H above. It is the maximum value that entropy

can take for a volume the size of the universe.

The internal observed entropy S, will of course, be much lower. I

don't have a formula for it off-hand, but it probably involves the

microwave background temperature.

Cheers

George Levy

George

Russell Standish wrote:

is 71 ± 4 (km <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kilometer>/s

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second>)/Mpc <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Megaparsec> which gives a size of the Universe <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Observable_universe> from the Earth to the edge of the visible universe. Thus R = 46.5 billion light-years in any direction; this is the comoving radius <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radius> of the visible universe. (Not the same as the age of the Universe because of Relativity considerations) Now I have trouble relating these facts to your equation H = C + S or maybe to the differential version dH = dC + dS. What do you think? Can we push this further? George

Russell Standish

notation which is a defacto standard for mathematical notation in

email.

Until someone figures out a way of getting all email clients to read

and write mathML (which will probably be never), this is as good as it

gets.

Cheers

--

Bruno Marchal

I have almost finished the posts on the lobian machine I have promised.

I have to make minor changes and to look a bit the spelling. I cannot

do that this week, so I will send it next week. Thanks for your

patience. I give you the plan, though, which I will actually also

follow for the beginning (and the end) of the ULB-saturday course this

year:

1) Cantor's diagonal

2) Does the universal digital machine exist?

3) Lobian machines, who and what are they?

4) The 1-person and the 3- machine.

5) Lobian machines' theology

6) Lobian machines' physics

7) Lobian machines' ethics

BTW, if some people are near Belgium, I have been invited for doing a

talk on the UDA at a colloquium on "Logic and Reality" at Namur/Louvain

in BELGIUM. The other talks seems quite interesting (too, if I may say

:). Most will be done in english. Program and informations can be found

here:

http://www.logic-center.be/acts/logrea.html

Best regards to David, and all of you

Bruno

David Nyman

> I have almost finished the posts on the lobian machine I have promised.

> I have to make minor changes and to look a bit the spelling. I cannot

> do that this week, so I will send it next week. Thanks for your

> patience.

Thanks - I'll keep an eye out.

David

John Mikes

John

Bruno Marchal

Le 11-nov.-07, à 23:33, John Mikes a écrit :

> Bruno, I hope it will be accessible to me, too, by simple computerese

> software.

Normally there should be no difficulties. My goal is not to explain all

the technics, but the minimal things which I estimate to be necessary

for having a basic general idea of what is going on.

My first goal, perhaps my main goal, is to explain Church Thesis CT.

To explain why CT is a very strong hypothesis, with a uniform deep

impact on everything, and mainly on "theories of everything".

I want also to explain more clearly the difference between Tegmark,

Schmidhuber, and "comp", etc.

But this needs a minimal amount of "modern math", so as to make clear

Cantor's role, and then Church, Kleene.

Not really the time today, but hopefully (normally) I will have more

time tomorrow,

Thanks for letting me know your interest, and your patience,

Best,

Bruno

Bruno Marchal

OK, here is a first try. Let me know if this is too easy, too

difficult, or something in between. The path is not so long, so it is

useful to take time on the very beginning.

I end up with some exercice. I will give the solutions, but please try

to be aware if you can or cannot do them, so as not missing the train.

John, if you have never done what has been called "modern math", you

could have slight notation problem, please ask any question. I guess

for some other the first posts in this thread could look too much

simple. Be careful when we will go from this to the computability

matter.

I recall the plan, where I have added the bijection thread:

Plan

0) Bijections

1) Cantor's diagonal

2) Does the universal digital machine exist?

And for much later, if people are interested or ask question:

3) Lobian machines, who and/or what are they?

4) The 1-person and the 3- machine.

5) Lobian machines' theology

6) Lobian machines' physics

7) Lobian machines' ethics

But my main goal first is to explain that Church thesis is a very

strong postulate. I need first to be sure you have no trouble with the

notion of bijection.

================

0) Bijections

Suppose you have a flock of sheep. Your neighbor too. You want to know

if you have more, less or the same number of sheep, but the trouble is

that neither you nor your neighbor can count (nor anyone around).

Amazingly enough, perhaps, it is still possible to answer that

question, at least if you have enough pieces of rope. The idea consists

in attaching one extremity of a rope to one of your sheep and the other

extremity to one of the neighbor's sheep, and then to continue. You are

not allow to attach two ropes to one sheep, never.

In the case you and your neighbor have a different number of sheep,

some sheep will lack a corresponding sheep at the extremity of their

rope, so that their ropes will not be attached to some other sheep.

Exemple (your flock of sheep = {s, r, t, u}, and the sheep of the

neighborgh = {a, b, c, d, e, f}.

s --------- a

r ---------- d

u --------- c

t ----------- f

------------e

------------b

and we see that the neighbor has more sheep than you, because b and e

have their ropes unable to be attached to any remaining sheep you have,

and this because there are no more sheep left in your flock. You have

definitely less sheep.

In case all ropes attached in that way have a sheep well attached at

both extremities, we can say that your flock and your neighbor's flock

have the same number of elements, or same cardinality. In that case,

the ropes represent a so called one-one function, or bijection, between

the two flocks. If you have less sheep than your neighbor, then there

is a bijection between your flock and a subset of your neighbor's

flock.

If those flocks constitute a finite set, the existence of a bijection

between the two flocks means that both flocks have the same number of

sheep, and this is the idea that Cantor will generalize to get a notion

of "same number of element" or "same cardinality" for couples of

infinite sets.

Given that it is not clear, indeed, if we can count the number of

element of an infinite set, Cantor will have the idea of generalizing

the notion of "same number of elements", or "same cardinality" by the

existence of such one-one function. The term "bijection" denotes

"one-one function".

Definition: A and B have same cardinality (size, number of elements)

when there is a bijection from A to B.

Now, at first sight, we could think that all *infinite* sets have the

same cardinality, indeed the "cardinality" of the infinite set N. By N,

I mean of course the set {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ...}

By E, I mean the set of even number {0, 2, 4, 6, 8, ...}

Galileo is the first, to my knowledge to realize that N and E have the

"same number of elements", in Cantor's sense. By this I mean that

Galileo realized that there is a bijection between N and E. For

example, the function which sends x on 2*x, for each x in N is such a

bijection.

Now, instead of taking this at face value like Cantor, Galileo will

instead take this as a warning against the use of the infinite in math

or calculus.

Confronted to more complex analytical problems of convergence of

Fourier series, Cantor knew that throwing away infinite sets was too

pricy, and on the contrary, will consider such problems as a motivation

for its "set theory". Dedekind will even define an infinite set by a

set which is such that there is a bijection between itself and some

proper subset of himself.

By Z, I mean the set of integers {..., -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, ...}

Again there is a bijection between N and Z. For example,

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ....

0 -1 1 -2 2 -3 3 -4 4 -5 5 ...

or perhaps more clearly (especially if the mail does not respect the

"blank" uniformely; the bijection, like all function, is better

represented as set of couples:

bijection from N to Z = {(0,0) (1, -1) (2, 1) (3 -2) (4, 2) (5, -3) (6,

3) ... }. Because everyone know the sequence 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, ... we

can also describe a bijection between N and Z (say) just by the

sequence of images:

0 -1 1 -2 2 -3 3 -4 4 -5 5 ...

That bijection can also be given by a rule: send even number x on x/2,

and send odd numbers on x -((x+1)/2). But it is not necessary to get

those rules to be convinced, the drawing is enough once you interpret

it genuinely.

By AXB, I mean the set of couples (x, y) with x in A and y in B. It is

natural to put them in a cartesian plane. For exemple, if A = {0, 1}

and B = {a, b, c}, then AXB = {(0, a) (1, a) (0, b) (1, b) (0, c) (1,

c)}, and is best represented by

(0, c) (1, c)

(0, b) (1, b)

(0, a) (1, a)

You see that if A is finite and has n elements and if B is finite and

has m elements, then AXB is finite and has m*n elements. Yet, again,

NXN "has the same number of elements" that N.

NXN is obviously the infinite extension of the following 4X4

approximation:

...

(0,3) (1,3) (2,3) (3,3)...

(0,2) (1,2) (2,2) (3,2)...

(0,1) (1,1) (2,1) (3,1)...

(0,0) (1,0) (2,0) (3,0)...

Do you see a bijection between N and NXN ?

Here is one, which I will call the zigzagger (draw the picture above

and draw the link between the couples, a bit like in little children

drawing puzzles, so as to see the zigzag clearly).

(0,0) (0,1) (1,0) (2,0) (1,1) (0,2) (0,3) (1,2) (2,1) (3,0) (4,0) (3,1)

(2,2) (1,3) (0,4) ...

Here is another one, due to Cantor, I think. To draw it you will have

to raise the pen.

(0,0) (0,1) (1,0) (0,2) (1,1) (2,0) (0,3) (1,2) (2,1) (3,0) (0,4) (1,3)

(2,2) (3,1) (4,0) ...

The inverse of that bijection, which exists and is of course a

bijection from NXN to N has a nice quasi polynomial presentation. (x,

y) is send on the half of (x+y)^2 + 3x + y.

You see that (4,0) is send to 14 (ok ?, it is not 13 because we start

from zero), and indeed the half of (4+0)^2 + 3*4 +0 is 14.

And ZXZ extends in a similar way :

...

... (-3, 3) (-2, 3) (-1,3) (0,3) (1,3) (2,3) (3,3)...

... (-3, 2) (-2, 2) (-1,2) (0,2) (1,2) (2,2) (3,2)...

... (-3, 1) (-2, 1) (-1,1) (0,1) (1,1) (2,1) (3,1)...

... (-3,0) (-2, 0) (-1,0) (0,0) (1,0) (2,0) (3,0)...

... (-3,-1) (-2,-1)(-1,-1) (0,-1) (1,-1) (2,-1) (3,-1)...

... (-3,-2) (-2,-2)(-1,-2) (0,-2) (1,-2) (2,-1) (3,-2)...

... (-3,-3) (-2,-3)(-1,-3) (0,-3) (1,-3) (2,-1) (3,-3)...

...

Do you see a bijection between N and ZXZ ? Here is the

spiral-bijection, or spiraler: