“An advice,” “a good news”: Errors of Pluralization in Nigerian English

Farooq A. Kperogi

By Farooq A. Kperogi, Ph.D.

Twitter: @farooqkperogi

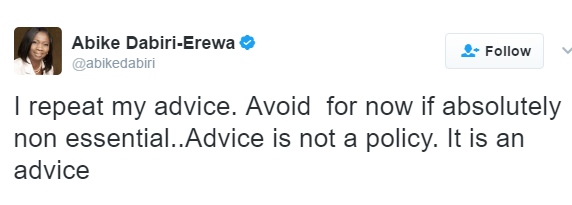

Many people called my attention to a tweet by Abike Dabiri-Erewa, President Muhammadu Buhari’s Senior Special Assistant on Foreign Affairs and Diaspora, who wrote that her travel warning to Nigerians to not travel to the US was just “an advice.”

That is, of course, grammatically incorrect. “Advice” is a non-count noun, which does not admit of the conventional singular and plural forms of regular nouns. In other words, there is neither “advices” nor “an advice.” The singular form of “advice” is expressed as “a piece of advice” (or just “advice”) and the plural form is expressed as “pieces of advice.”

Dabiri-Erewa, who is incidentally a graduate of English from the Obafemi Awolowo University, is not alone in the practice of unconventionally singularizing and pluralizing uncountable nouns.

In an April 14, 2010 article titled “Common Errors of Pluralization in Nigerian English,” I pointed out that, “One notable feature of Nigerian English is the predilection for adding plural forms to nouns that don’t normally admit of them in Standard English. This is certainly a consequence of the inability of many Nigerian speakers and writers of the English language to keep up with the quirky, illogical irregularities that are so annoyingly typical of the conventions of English grammar.”

How English Plurals Are Formed

It’s common knowledge that the plural form of most nouns in English is created by adding the letter “s” to the end of nouns. But sometimes it requires adding “es” to nouns that end in “ch,” “x,” “s,” or s-like sounds, such as “inches,” “axes,” “lashes,” etc. There are also, of course, irregular forms like “children” as the plural of “child,” “oxen as the plural of “ox,” etc.

Then you have uncountable—or, if you will, “non-count”— nouns, which cannot be modified or combined with the indefinite articles “a” or “an.” This is precisely where Nigerians fall foul of standard usage norms.

Irregular noun plurals

Most educated Nigerians generally know that nouns like equipment, furniture, information (except in the expression “criminal informations,” or “an information,” which is used in the US and Canada to mean formal accusation of a crime, akin to indictments), advice, news, luggage, baggage, faithful (i.e., loyal and steadfast following, as in, “millions of Christian and Muslim faithful”), offspring, personnel, etc. remain unchanged even when they are expressed in a plural sense. But few know of many other nouns that have this characteristic.

Unconventional noun singularizations in Nigerian English

Although most educated Nigerians would never say “newses” or “advices” or “informations” to express the plural forms of these nouns, they tend to burden the words with singular forms that are not grammatical. For instance, they would say something like “that’s a good news” or “it’s just an advice” or “it’s an information for you.”

Well, since these nouns don’t have a plural form, they also can’t have a singular variant, that is, they cannot be combined with the definite articles “a” or “an.” So the correct way to render the sentences above would be “that’s a good piece of news” (or simply “that’s good news”), “it’s just a piece of advice” (or “it’s just advice), and “it’s information for you.”

Other nouns that are habitually pluralized wrongly in Nigerian English are:

“Legislations.” Nigerians inflect the word “legislation” for grammatical number by adding “s” to it. The sense of the word that denotes “law” (such as was used in this Punch headline: “Nigerians need legislations that will ease their problems –Cleric”) does not take an “s” even if it’s used in the plural sense. In Standard English, the word’s plural form is usually expressed with the phrase “pieces of,” or such other “measure word” (as grammarians call such expressions).

So the headline should correctly read: “Nigerians need pieces of legislation…” or simply “Nigerians need legislation….” However, the sense of the word that means “the act of making laws” may admit of an “s,” although it’s rare to encounter the world “legislations” in educated speech in Britain or America.

“Rubbles.” Another noun that Nigerians commonly add “s” to in error is “rubble,” that is, the remains of something that has been destroyed or broken up. This word is never inflected for plural. It’s customary to indicate its plural form with the measure word “piles of,” as in, “piles of rubble.” (Grammarians call words that are invariably singular in form “singulare tantum”).

“Vermins.” Similarly, the word “vermin,” which means pests (e.g. cockroaches or rats) — or an irritating or obnoxious person— is invariably singular and therefore does not require an “s” or the indefinite article “a.” But in Nigerian English it’s common to encounter sentences like “they are vermins” or “he is a vermin.”

“Footages/aircrafts.” “Footage” and “aircraft” are also invariably singular. So it’s nonstandard to either say or write, as many Nigerian do, “a footage” or “footages,” “an aircraft” or “aircrafts.” Dispense with the “s” at the end of the nouns and the indefinite articles “a” and “an” at the beginning.

“Heydays.” There is nothing like “heydays” in Standard English. It remains “heyday” even if the sense of the word is plural.

“Yesteryears.” Yesteryear is also invariably singular and does not change form when it expresses a plural sense. Only Nigerian English speakers and perhaps other non-native English speakers pluralize “yesteryear.”

“Cutleries.” Cutlery always remains “cutlery” even if you’re talking of millions of eating utensils.

“An overkill.” In Standard English, “overkill” is usually uninflected for number. So, where Nigerian English speakers would say “it’s an overkill,” people who speak standard varieties of English simply say “it’s overkill.”

“Slangs.” Nigerian English speakers habitually pluralize slang as “slangs” and singularize it as “a slang.” That’s unconventional. The Standard English plural forms of “slang” can be just “slang” (as in, “he speaks a lot of slang”) or “slang words,” or “slang terms,” or “slang expressions.” The singular form is simply “slang” (as in, “that was slang”).

“Invectives.” The word’s plural form is expressed by saying “a stream of invective,” not “invectives.”

“Beehive of activities.” The expression “beehive of activities,” which is common in Nigerian English, is nonstandard. It is usually rendered as “a beehive of activity” (also “a hive of activity). Its plural form is “beehives of activity” (or “hives of activity”). When “activity” means a “situation in which something is happening or a lot of things are being done,” it is usually uncountable.

So, it should be “a lot of economic activity,” not “a lot of economic activities.” It should be “physical activity,” not “physical activities.”

The only sense of “activity” that is pluralized is the sense that means “a thing that you do for interest or pleasure, or in order to achieve a particular aim,” such as “outdoor activities,” “leisure activities,” “criminal activities,” etc.

“Potentials.” It is usual in Nigerian English, even educated Nigerian English, to pluralize “potential” as “potentials,” particularly in the expression “Nigeria has great potentials.” In Standard English, however, “potential” is often uninflected for number, that is, it remains “potential” even if its sense is plural.

Why Native Speakers Don’t Pluralize These Nouns

As I’ve observed and chewed over these admittedly vexatious English plural forms over the years, I have been struck by the fact that I’ve never encountered any native speaker of the English language who has flouted these rules in speech or in writing. Not even my American college students who can be lax and slipshod with their grammar.

I think this is a consequence of the force of example. When people grow up not hearing older people say “an advice,” “a good news,” “legislations,” “vermins,” etc., they unconsciously internalize and make peace with the illogical irregularities that these exceptions truly are.

Related Articles:

School of Communication & Media

Kennesaw State University

Cell: (+1) 404-573-9697

Personal website: www.farooqkperogi.com

"The nice thing about pessimism is that you are constantly being either proven right or pleasantly surprised." G. F. Will

Cornelius Hamelberg

Corrected:

Another link from my last posting that got lost in transition : Besserwisser

I'm impressed by the very correct English spoken by the Democratic Republic of the Congo's Moïse Katumbi .The British English besserwisser grammarians who genuflect in the direction of their qibla which is Buckingham Palace, can judge for themselves this his spoken performance . I for one understood him perfectly and his performance, in my view, was flawless. I wish that I could speak Mandarin Chinese or French or Lingala or Nigerian English at something like that level.

I don't suppose that the kinds of people who subscribe to the USA-Africa Forum are in need of these kind of language columns, but of course, the English Language scholar could have chosen to be doing it as a do-good social service , a kind of Pied Piper to his English language disciples

It would be far too tedious and almost meaningless to take it item by item, but just this one on advice should suffice. As for the other one, you kick his ass and he says, "I don't understand"

According to The Devil's Dictionary : Advice

"Many people " called his attention (Professor Farooq Kperogi's) to the tweet by Abike Daiquiri-Erewa. To be as precise as he would like everybody to be when observing the changing rules and regulations and laws of strangulation drafted by Her Majesty's Language still undergoing evolution, I should like to ask, " Exactly how many people, drew his attention to what in my personal opinion was an al- right tweet or telegram either as an official or an unofficial communiqué (and I would be prepared to put my head under the guillotine for it) :

I have always assumed that the language employed by the various ministries of foreign affairs the world over is aimed at communicating with fellow citizens and diverse members of the international community and that just like the newsreaders in English in several countries that do not have English as the mother tongue, concessions are made to local accents, language usage, in fact often to accents approximating the national English accent. So in Radio Sweden this is what you hear.

However, strictly speaking, when it comes to grammar or the precise meanings embedded in legalese , foreign ministries had better be extra careful ! The example that comes to mind immediately is UN Resolution 242 which up to today is still experiencing all kinds of twists and arrows of outrageous fortune, all based on differences in opinions about the meaning/s of "occupied territories" and "the occupied territories". Ultimately, the judges as to the implications of the legal meanings are international jurists who insist that the differences cannot be merely local, partisan understandings or interpretations of the English Language as used in international documents / agreements.

In the case under Prof Kperogi's magnifying glass, first and foremost everybody understands the advice that's being given.

Hopefully, the creative writers, poets, dramatists, songsters, will regularise some of what the language police and Her Majesty’s "Linguistic sanitary inspector" believe to be highly irregular as used by members of the Naija English Club - the latter a phrase that I got from cousin Kayode Robbin-Coker, himself an HMS ( in Her Majesty's Service) "language sanitary inspector " and a former inspector of schools. (I was infinitely more familiar with our elder, Adeneka Lincoln Robbin-Coker, in his day, a diamond miner...)

This too is cultural :

Rogie: Advice to Schoolgirls

Olayinka Agbetuyi

Listserv moderated by Toyin Falola, University of Texas at Austin

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfric...@googlegroups.com

To subscribe to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDial...@googlegroups.com

Current archives at http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

Early archives at http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "USA Africa Dialogue Series" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to usaafricadialo...@googlegroups.com.

For more options, visit https://groups.google.com/d/optout.

Assensoh, Akwasi B.

Dear Brothers & Sisters:

The "Errors of Pluralization" debate did remind me of my old Nigerian mentor: In the mid-1960s, my old and legendary mentor, Baba Ijebu ("Ajebu") used to share with me some of the intellectual arguments among Nigerian scholars published in such Nigerian newspapers as DAILY TIMES, SUNDAY TIMES, LAGOS WEEKEND, TRIBUNE, SKETCH, etc. He would end by telling me: "The problems we have in Nigeria keep on multiplying because of people with book long qualifications."

Baba Ijebu often added his amazement that when he was in school, coming home with "D" grade on any class assignment was unacceptable. He exclaimed often about the fact that, in our day, important academic and professional degrees were riddled with "D", icluding: DDS; Ph.D.; DSC; MD; EDD; OD or DO; etc.

Baba Ijebu would have looked at the argument(s) and said: "Baba Ghana, na good grammar we dey chop?" He would, instead, praise the good looks of our sister (Abike Dabiri-Erewa), and probsbly add: "Be satisfied with whatever she says!" I echo that; also, I suggest that in West Africa, we should start identifying or thinking about having African Languages as the lingua franca for our various nations; we can learn from East Africa, where Ki-Swahili plays a major role. In that way, the pro-Queen's English debate among West African intellectuals may cease! Abi?

A.B. Assensoh.

Sent: Sunday, March 12, 2017 7:40 PM

To: usaafric...@googlegroups.com

Subject: Re: USA Africa Dialogue Series - Re: “An advice,” “a good news”: Errors of Pluralization in Nigerian English

Kenneth Harrow

“(I know that the typical ivory tower grammarian looks down on the communicative success of the ' drop outs ' but the world outside the ivory towers is the litmus test of reality and prescriptive grammars versus the continual evolution of language.”

Upon what is this claim based? Do you know what is taught at American universities, ola?

Or are you imagining it?

Do you know how many classes or seminars are offered in hip hop or rap? How many dissertations now are based on it?

Ken harrow

Kenneth Harrow

Dept of English and Film Studies

http://www.english.msu.edu/people/faculty/kenneth-harrow/

Farooq A. Kperogi

School of Communication & Media

Kennesaw State University

Cell: (+1) 404-573-9697

Personal website: www.farooqkperogi.com

"The nice thing about pessimism is that you are constantly being either proven right or pleasantly surprised." G. F. Will

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue@googlegroups.com

To subscribe to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue+subscribe@googlegroups.com

Current archives at http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

Early archives at http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "USA Africa Dialogue Series" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to usaafricadialogue+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

For more options, visit https://groups.google.com/d/optout.

--

Listserv moderated by Toyin Falola, University of Texas at Austin

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue@googlegroups.com

To subscribe to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue+subscribe@googlegroups.com

Current archives at http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

Early archives at http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "USA Africa Dialogue Series" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to usaafricadialogue+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

Cornelius Hamelberg

Cornelius Hamelberg

We have discussed "faithfuls" before

N.B. One does not need to invoke anything like "poetic license" to say "Beehive of activities"

In my opinion and in the opinion of some other native speakers it's absolutely kosher but maybe not halal for the Nigerian masses.

Hopefully, we don't have to argue about potentials...

Good song : Englishman in New York

On Sunday, 12 March 2017 18:31:03 UTC+1, Farooq A. Kperogi wrote:

Farooq A. Kperogi

School of Communication & Media

Kennesaw State University

Cell: (+1) 404-573-9697

Personal website: www.farooqkperogi.com

"The nice thing about pessimism is that you are constantly being either proven right or pleasantly surprised." G. F. Will

Maybe, because I reminise a lot I say Yesteryears although I am absolutely a native speaker and absolutely correct every time I say YESTERYEARS. I visited Izzy Young today, he reminisced a lot about New York etc about two hours, and I reminisced a lot about the Stockholm of yesteryears...

Cornelius Hamelberg

On Monday, 13 March 2017 22:20:55 UTC+1, Farooq A. Kperogi wrote:

Being a "native English speaker" isn't the same thing as being a speaker of Standard English. They are different. Many native speakers don't speak Standard English; they speak their regional varieties. With education, they learn Standard English. There is, strictly speaking, no native speaker of Standard English.It's a consciously learned variety of English, although it is true that it is made up of parts from different native regional varieties."Yesteryears" is demonstrably solecistic in Standard English. I don't know the regional native English variety you speak that countenances "yesteryears." My own research tells me "yesteryears" is used mostly by non-native English speakers. Standard English speakers say "days of yesteryear" to pluralize "yesteryear." In fact, all the regional native varieties I am familiar with never say "yesteryears."Farooq

Farooq A. Kperogi, Ph.D.Associate ProfessorJournalism & Emerging Media

School of Communication & MediaSocial Science BuildingRoom 5092 MD 2207402 Bartow Avenue

Kennesaw State UniversityKennesaw, Georgia, USA 30144

Cell: (+1) 404-573-9697

Personal website: www.farooqkperogi.comTwitter: @farooqkperogAuthor of Glocal English: The Changing Face and Forms of Nigerian English in a Global World

"The nice thing about pessimism is that you are constantly being either proven right or pleasantly surprised." G. F. Will

On Mon, Mar 13, 2017 at 2:52 PM, Cornelius Hamelberg <cornelius...@gmail.com> wrote:

Maybe, because I reminise a lot I say Yesteryears although I am absolutely a native speaker and absolutely correct every time I say YESTERYEARS. I visited Izzy Young today, he reminisced a lot about New York etc about two hours, and I reminisced a lot about the Stockholm of yesteryears...

--

Listserv moderated by Toyin Falola, University of Texas at Austin

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfric...@googlegroups.com

To subscribe to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDial...@googlegroups.com

Current archives at http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

Early archives at http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "USA Africa Dialogue Series" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to usaafricadialo...@googlegroups.com.

Cornelius Hamelberg

I have also been reading continuously since I was six years old. I think that Patrick White is a great novelist. My wife is a native speaker of "standard Swedish" from which she sometimes translates ( also speaks Spanish, French, Italian, and of course English and is very much a grammarian...

On Monday, 13 March 2017 22:20:55 UTC+1, Farooq A. Kperogi wrote:

Being a "native English speaker" isn't the same thing as being a speaker of Standard English. They are different. Many native speakers don't speak Standard English; they speak their regional varieties. With education, they learn Standard English. There is, strictly speaking, no native speaker of Standard English.It's a consciously learned variety of English, although it is true that it is made up of parts from different native regional varieties."Yesteryears" is demonstrably solecistic in Standard English. I don't know the regional native English variety you speak that countenances "yesteryears." My own research tells me "yesteryears" is used mostly by non-native English speakers. Standard English speakers say "days of yesteryear" to pluralize "yesteryear." In fact, all the regional native varieties I am familiar with never say "yesteryears."Farooq

Farooq A. Kperogi, Ph.D.Associate ProfessorJournalism & Emerging Media

School of Communication & MediaSocial Science BuildingRoom 5092 MD 2207402 Bartow Avenue

Kennesaw State UniversityKennesaw, Georgia, USA 30144

Cell: (+1) 404-573-9697

Personal website: www.farooqkperogi.comTwitter: @farooqkperogAuthor of Glocal English: The Changing Face and Forms of Nigerian English in a Global World

"The nice thing about pessimism is that you are constantly being either proven right or pleasantly surprised." G. F. Will

On Mon, Mar 13, 2017 at 2:52 PM, Cornelius Hamelberg <cornelius...@gmail.com> wrote:

Maybe, because I reminise a lot I say Yesteryears although I am absolutely a native speaker and absolutely correct every time I say YESTERYEARS. I visited Izzy Young today, he reminisced a lot about New York etc about two hours, and I reminisced a lot about the Stockholm of yesteryears...

--

Listserv moderated by Toyin Falola, University of Texas at Austin

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfric...@googlegroups.com

To subscribe to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDial...@googlegroups.com

Current archives at http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

Early archives at http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "USA Africa Dialogue Series" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to usaafricadialo...@googlegroups.com.

Farooq A. Kperogi

School of Communication & Media

Kennesaw State University

Cell: (+1) 404-573-9697

Personal website: www.farooqkperogi.com

"The nice thing about pessimism is that you are constantly being either proven right or pleasantly surprised." G. F. Will

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue@googlegroups.com

To subscribe to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue+subscribe@googlegroups.com

Current archives at http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

Early archives at http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "USA Africa Dialogue Series" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to usaafricadialogue+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

Kenneth Harrow

I certainly do not want to get in the middle of this, so consider my remarks on the side, and not trying to take sides.

I learned English by hearing it spoken,-- by my parents, and people around me.

I learned to say, it’s me, if someone said, who’s there

I learned to say, he knows more than me.

And many more constructions, that happen to be wrong. It was very difficult for me to learn, in high school and more likely in college, that these ways of speaking were incorrect since they felt completely right. After all, my parents spoke that way, and so did everyone else.

Now when I answer the phone I say, it’s I, not it’s me. I say, he knows more than I. I practically cannot say it otherwise since I corrected my students for making those errors for 50 years. You can say my spoken English is now deformed by the training to use correct, but not idiomatically normal speech in my pedagogy.

I think the answer to the question who is a “native speaker” is one who learns a language by speaking it, whether it is the first or nth language. What we learn in school is correct, but not necessarily normally spoken. And that’s the French I learned, and which at times makes it harder for me to understand the spoken language.

I’ll give an example of weirdness in this. when I moved to Michigan I learned that the store we shopped in for groceries was called meijer’s. that’s what everyone here called it. But the sign on the store is Meijer. I recently learned that Michigan is the only place in the country where the norm is to add ‘s to company names. It dates back, apparently, to when Ford opened a factory here, and people called it Ford’s. since then other establishments came to be assigned the possessive, for no good reason. Now outsiders who move to Michigan, and don’t have that pattern in their speech, say Meijer, where others like me, who learned to say it differently, continue with the inherited misuse.

Language usage is truly weird, and very fascinating.

ken

Kenneth Harrow

Dept of English and Film Studies

http://www.english.msu.edu/people/faculty/kenneth-harrow/

Cornelius Hamelberg

"A hotbed of intrigue/ intrigues"

Indeed, familiarity does breed contempt. And indeed just as this year's Polar Prize winner Sting sang some time ago,

"If "Manners maketh man" as someone said

Then

he's the hero of the day

It takes a man to suffer ignorance and

smile

Be yourself no matter what they say"

(Englishman

in New York)

Whose permission do I need to be or not to be, to think or not to think, to dream or not to dream the impossible dream in your beloved universal or Buckingham palace "standard English"? And exactly what is it? Is that what you speak? Is that what Sheikh Speare wrote or spoke ? Apart from a few gross grammatical errors in that little colloquial BBC blip, you sound like my friend who has never been overseas and is still rooted in Kumasi. You want to teach me English?

Pathetic.

Methinks that thou shouldst better stick to thine own comfort zone :

"Nigerian English" where you actually feel most at home.

I did not, nor do I need to proclaim my "native speakerness". I mentioned it just this once and in this discussion that you instigated. I know that you are distraught at the very thought that you are not and therefore cannot boast of the so called "native speakerness". Sorry about that. My honest opinion is that if it's your ambition to make standard English speakers out of Nigerians, you had better start with yourself. Then you could be a role model.

In my case, and ever so accidentally, it's a natural part of me, it's my language, it's what I do when I open my mouth and when somebody impolitely tells me to shut up, even when I close it, it's the language of the thoughts that run around in my head - as natural as Hausa or whatever it is that you speak and that is natural to you. There are over a hundred million such speakers. It’s nothing special - it's as special as a billion Chinese who speak Chinese - they don't have to quote Wole Soyinka about "Tigritude" pouncing, nor do I in order to demonstrate by formally/informally kicking somebody's ass in the lingo which you respect so much or want to glorify or sing hallelujah about. I don't.

It's just the colonial complex that is so feverishly at work in you, bristling at the whiskers

and at the pubic hairs going up those public stairs

sometimes I feel word-drunk like Eliot

"If you remember me, my Lord, at your prayers,

I'll remember you at kissing-time below the stairs".

And just who made Farooq Kperogi an expert on "Standard English"? You're not British or English or Scottish or Irish or Welsh, at least you don't sound like one. You don't want to become a living caricature or the butt end of cruel jokes about Her Majesty the Queen's " Standard English "do you? That Nigerian or first generation Baga-Nigerian American guy who wants to set himself up as an authority over the English speaking Empire? In that case I could take apart / disembowel your little blip on the BBC or anything that you write/ have written, formally/ informally. Trust me. ( I have looked at the diction in chapter one of Chigozie Obioma's "The Fishermen" a fantastic tragedy - why he chooses one word and not the other that's more conveniently at hand (about ten examples) but what purpose other than futility would it serve to write a fulsome article/ essay on that and forward it to some relevant outlet for such thoughts?)

Farooq, I'm going to be short here - by which I don't mean that I'm going to be impolite or rude to you. I just woke up of from a dream in which I was in Cochin and speaking English. I just told my Better Half about it. I should have written the details down. Shalom, my Sephardic friend - I think he was a Kabbalist, could remember and narrate in great detail dreams he had decades ago. How? I asked him, the second to last time I met him in this life. Just grab any detail of the dream that you remember - hold on to it, grasp it, meditate on it, try to remember and like a thread it should lead you back to the beginning of the dream and voilà with a little concentrated effort you achieve total recall. That's what he told me. Total recall of a long story that - as dreams go - probably only lasted a few seconds - or like the Prophet of Islam's miraj - a billionth of a second! The second thing I noticed (I won't tell you the first) was that most of the dreams he told me sounded like didactic stories (sort of) . I understand that one of the factors contributing to the dream I had this morning was reading Vik Bahl's posting The World Wildlife Fund, Trophy Hunters and Donald Trump Jr. and at the time and exactly just now, and from my yesteryears, from way back in 1977 in India, my own fond memory of Ganesh, the elephant at Shree Gurudev ashram at Gansehpuri at the time known as Shree Gurudev Siddha Peeth which is 47 miles away from Mumbai - in those days (yesteryears) known as Bombay, which is in Maharashtra state, where they speak the Marathi language, but Baba communicated with us in Hindi which was translated into English by Malti, now known as Gurumayi Chidvilasananda. There's a picture of Diana Ross riding that elephant - in Time magazine - when she visited at exactly the same time I was there. Apart from its fabled memory one more thing that we should know about the elephant - not just in Sanskrit lore, is its immense sense of touch.

All of the above is a short specimen of written English - in which there are several types of English/ Englishes - " kick your ass " cowboy-speak etc., but no particular features of your Nigerian English - but you should know better, since I am neither a native speaker nor a speaker of your Nigerian English - although, as an actor I can imitate any kind of spoken English that you would demand of me - Prince Charles, Forrest Whitaker ( approximately) ,Lady Macbeth, slightly more difficult , Wole Soyinka....I'll tell you a 419 story a little later , this week...

I hope that you are not about to disqualify George Orwell / Eric Blair who you quote - disqualify him from speaking any of the forms of standard English - because he was born in India or the impious Salman Rushdie, on the same grounds, for having been born in Bombay, the headquarters of Bollywood.

I attended primary school in Fulham, where I acquired the accent of that area and some of the culture that goes with it, Charlotte and I (I was one class ahead of her) being brought up by her parents ( my guardians) John Jeffrey-Coker and Aunt Nelly at 144 Sinclair Road where we lived, 1952-1955. Aunt Nelly (Charlotte’s mother - from Holland and indeed her brother Nigel) and Uncle Jeff instilled good manners in us - for example we distinguished between fibs and lies, said yes please and no thank you, wielded our knives and forks correctly, knew how to use our handkerchiefs

I had a Scottish step-father (John Patrick Johnson, Dundee, Glasgow, Edinburgh a decorated WW2 Naval Officer ) and of course, I speak and can write a very correct English and be a perfect gentleman when I so desire - have no qualms about meeting royalty and apart from periods of travel have mostly lived within an English language community, all of my life. There's also a culture , customs, traditions even a sense of humour, music/ musicality, dance, poetry, that comes with the language that you’re talking about. In 1963 - along with Violetta Luke and William Fitzjohn the other winners of an oral English prize awarded by the British council for our "O" level English performance, I read the evening news on SLBS a couple of times shortly thereafter - couldn't recognise my own voice ( people complained it was too British) but the same hypocrites never complained about Hannah Bright-Taylor or my first cousin Martin Williams who were news readers around that time. Much later, the drummer in our band Gipu Felix-George became the director of the SLBS.

Dear Farooq, when we sat for our "A "levels in English I smiled at little when I looked at the unseen piece of poetry ( piece of advice?) it was Ted Hughes' On the Move about the ton-up boys and no stranger to me in connection with D.H. Lawrence's "Sons of Lovers" I had gone past the oedipus complex. I think that I killed that paper. I must have. I must correct a mistake I made yesterday: My Better Half does not translate from Swedish, she translates from British/ American / New Zealand English into her mother tongue which is Swedish. She also studied English at the University of Washington which is in Seattle. Among the books that she has translated is Bruno Bettelheim's The Empty Fortress // Den tomma fästningen: infantil autism - symtom och behandling ( 516 pages ) which she mostly translated when we were in Nigeria). Last week she was teaching Ph.D. students Swedish as a foreign language. She speaks perfect English and I am of course one of her best students, all languages.

What do you make of the marginal man theory?

Before you dare reply to this - so that I may really pounce on you like a Bengal tiger and without any warning - in non-standard English if you please - remember what King Solomon said: All is vanity...

Now I must be off to see IZZY!!!!

Farooq A. Kperogi

School of Communication & Media

Kennesaw State University

Cell: (+1) 404-573-9697

Personal website: www.farooqkperogi.com

"The nice thing about pessimism is that you are constantly being either proven right or pleasantly surprised." G. F. Will

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue@googlegroups.com

To subscribe to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue+subscribe@googlegroups.com

Current archives at http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

Early archives at http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "USA Africa Dialogue Series" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to usaafricadialogue+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

Cornelius Hamelberg

Correction : Grammar (typographical) :Dear Farooq, when we sat for our "A "levels in English I smiled a little when I looked at the unseen piece of poetry..

Other corrections : my first cousin EDDIE Williams who was an SLBS news reader ( later on, for many years until recently, he ran a radio station on St: Martin , an island in the Caribbean )

In our time in secondary school we had great teachers - our art teacher Guy Massie-Taylor, in French Mr. White ( Canadian) and A.W. Rogers (Belgian) in English Mrs Fewry, Mr. Chapman (MA. Cantab) , Mr. Davies, in the fourth form Major A T von S Bradshaw ( a great admirer of China) in lower six Michael Brunson (who gave spoken life to the written word - he had read theology at Oxford where he was active in amateur theatre) and in upper six Bankole Thompson (affectionately known as "Banky" ( then a Wordsworth freak) an dof great importance at that time, The British Council

Cornelius Hamelberg

Dear Farooq,

What a boor you are!

I would say that "I am a native speaker" and I speak an educated, what you or your employers would call "standard English"

Emeagwali, Gloria (History)

"Shakespeare did not write Standard English because there was no Standard English when he lived. "Standard English"

started life only in the 18th century,"

?????

Sent: Tuesday, March 14, 2017 11:16 AM

To: USA Africa Dialogue Series

Kenneth Harrow

Shakespeare wrote in Elizabethan English. If you don’t thinkthat is different from standard English of today, just try reading some of his plays!!

They are just on the cusp of becoming incomprehensible to today’s speakers.

Furthermore, there were no institutions to standardize it. The spellings were completely up to publishers who made up different spellings as they saw fit.

Lastly, if you move from lansing Michigan to new York, you can say we use different words for different things, like pop vs soda etc. imagine living in a country without tv or radio to give a common language. Moving from one town to another would have created problems; and if you just try to understand the speech of northern English people now, you’ll get the point. Farooq is right: people who know English can read this message and understand it, but at home the speech in one place will certainly differ from that of another place.

ken

Kenneth Harrow

Dept of English and Film Studies

http://www.english.msu.edu/people/faculty/kenneth-harrow/

Cornelius Hamelberg

God created the universe with the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet

Long after the tower of babel , where the babble began

These opening lines so many beginners remember

Some lucky ones started even earlier

Today I look for this spell-checker

Others search desperately for Zimbabwe. Fact is

Man Friday has to adjust to the local conditions of wanderlust :

For better, for worse, when in Rome do as Rome does

If necessary Harrow, sings like a sparrow...

Olayinka Agbetuyi

Kenneth Harrow

Dear olayinka

I agree there are different “standard” englishes. One way to see it clearly is the language we teach. In Europe, a good number of years ago, they began to distinguish between the British and American variety by actually calling them English and American, or American English . when you signed up to learn the language, they made that distinction. We had a French boy, studying English, living with us here in Michigan, and he would correct our American English, or else simply not use it, for his homework assignments where he had learned the british variety.

Still, we do teach standard English—no doubt about it. Only we teach different varieties, and Nigerian English has to be taught in Nigeria or else some other variety will come to prevail.

(lots of jokes about the difference, especially when it comes to underwear, or whatever they call it in England and Nigeria)

also consider India with its enormous population learning a different variety there as well.

All this not to mention the really greatest difference, which is accent. That part is fascinating.

ken

Kenneth Harrow

Dept of English and Film Studies

http://www.english.msu.edu/people/faculty/kenneth-harrow/

Olayinka Agbetuyi

Cornelius Hamelberg

Dear Ken,

I wish that I could write this in Standard French or in Haitian French...

If the word is still free, I should like to clear the air, somewhat. This, after visiting John Andrews, my friend from California, this afternoon. A tear nearly came to his eye when he started singing in praise of the weather the year round, in California ...

This is part of a diary. I'm taking notes. If ever I touch this or any other topic about Naija or any place else it’s mainly to promote/ participate in or even be at the tail end of some kind of discussion.

This too, the lines in this posting are purely theatre from my point of view and you are one of many charterers in this drama, sometimes an avuncular overseer and patron to chaps like Ikhide, Adesanmi, Ochonu, Mbaku. Personally, I love, admire and respect the principles, honesty, forthrightness and dedication of, obviously, e.g. Ogbeni Kadiri, Chidi, IBK, Samuel Zalanga, Sabella Ogbobode Abidde.

There is also the impeccable - Oga Falola - sacrosanct , alone and all by himself in the special category...

(My friend says that the monotheists are those who believe in a highly centralised government - One God - whereas the polytheists believe in decentralisation, deregulation, relegation of powers (angels and messiahs, bishops, pastors, priests) and regional autonomy. As you can see, I'm strictly monotheist. Slightly on the other plane but not parallel with the Oga of Ogas - sort of on the level of the archangels, Chief Bolaji Aluko, Ayo Olukotun, and on the spiritual and angelic level - on the spiritual slope, like a lullaby , Funmiara, Jibrin Ibrahim, Rasfanjani. Then there are the rebels, like Gloria in excelsis Emeagwali and Toyin Vincent Adepoju. You may notice that I haver left the literati out of this judgement.

Happily, there are no demons in this forum. There is sometimes ignorance, yes, as one Rabbi prayed, "Father forgive them for they know nothing!", there are a couple of islamophobes and arrogance, yes, but not on the same level as Iblis...

I have no respect for those empty buckets who don't know Shakespeare and want to preach about him to those who were and are still his students, long before the empty bucket could begin to grasp the rudimentary Arabic alphabet. To tell you the truth, I enjoyed reading Amos Tutuola and fully understand and enjoy Nigerian Broken but I really don't give a damn about Nigerian English really, especially not some of the pretentious , highfalutin pontificating about it, some of which is as absurd as the same mutha something trying to correct Ebonics, saying it is out of line and trying to align it with (some quaint notions of) the state of the English Language in the last century when his Pa Blair was still alive. It's equally absurd trying to "correct" a rap dictionary - who di hell be he?

In Sweden we mostly speak Swenglish and nearly all of the examples I can give of malapropism etc. are hilarious. There are quite a few words that Swedish and Scottish have in common due to yesteryears' relations between the Scots and the Scandinavian Vikings, words such as barn (child) kyrka (church). Outside of Scandinavia, Germans learn Swedish more easily than e.g. Americans...

Fresh from Ghana, Cornelius Ignoramus' first teaching job in Sweden was at TBV (one of the leading language school of that era.) In the spring of 1972, I was employed by David Austin who said that I had a "British" type of accent and that seemed to additionally qualify me to run a course in "Advanced Conversation". Twice a week in the evenings ( after the first meeting the students suggested that)the rest of the classes were held alternately in students homes - to get away from the boring institutional atmosphere / environment - we put it to the vote (mostly young to middle aged ladies) who also, eventually, occasionally took out the china and so we had nice cups of tea in between talking about Big Ben, Buckingham Palace, Westminster Abbey, the Houses of Parliament, Hyde Park, au pair girls, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, underwear, Women's Liberation.

In teaching English in Sweden and in Nigeria the same set of teething problems, namely home language interference - in the Swedish case mostly prepositions and in the case of Nigeria quite a different cultural environment and some of the hangups of its post-colonial culture going back to since the days of slavery (calling me Sir for example) pidgin being so close to the British English language thing, indeed a part of it , a close cousin, brother, other , of course localisms which serve their creative/communicative functions - expressions such as " 'Ow now / Ow weder (weather) - How are you..."the man is not on seat" ( out of the office) she has just put to bed ( she just gave birth to ...)

There was Chairman Mao's Paper Tiger ...

Fast forward, the situation we are in is akin to the first few paragraphs of Aravinda Adiga's The White Tiger which won the Booker Prize in 2008:::

"The First Night

For the Desk of:

His Excellency Wen Jiabao

The Premier's Office

Beijing

Capital of the Freedom-loving Nation of China

From the Desk of:

The White Tiger"

A Thinking Man

And an Entrepreneur

Living in the world's center of Technology and Outsourcing

Electronics City Phase 1 (just off Hosur Main Road)

Bangalore, India

Mr. Premier,

Sir.

Neither you nor I speak English, but there are some things that can be said only in English. "

Except of course if such a novel of the imagination were to be peopled by at least one outstanding character with a sense of humour and the action were to be situated in Nigeria and given the title "The Black Tiger", I for one could imagine the president’s little besserwisser speechifying speech-writer , professor wet chicken feather or professor chicken wings trying to write/ imitate the immaculate British English which I teach, or the American/Austr-alien/New Zealand/ Canadian/South Africa/ Zimbabwe English varieties with which we are so deeply familiar through their literature of both the written and the spoken word oft-times through direct contact, referred to as the oral tradition , I imagine that the little besserwisser who really doesn't know any better,would preface his letter thus:

"As someone or the other once suggested, a tiger does not proclaim his Negritude; he pounces but I must confess that BTW, I had better say it out , I'm black and proud and that's why I believe that in the national interest there are some things that can only be said in Nigerian English - and that the rest had been better left unsaid..."

Best Regards,

etc. etc. etc.

Cornelius

On Tuesday, 14 March 2017 22:29:24 UTC+1, Kenneth Harrow wrote:

Emeagwali, Gloria (History)

Thanks for the clarification.

So Standard English has a shelf life. Right?

Elizabethan English was standard in its day but fell out of fashion, somewhat.

Sorry Ken but I don't understand your last sentence:

"people who know English can read this message and understand it,

but at home the speech in one place will certainly differ from that of another place."

Are you talking about coding and the fact that speakers of the language switch codes to suit

the audience - or what? Kindly clarify.

Sent: Tuesday, March 14, 2017 5:18 PM

To: usaafricadialogue

Cornelius Hamelberg

Sir,

"Here I go, deep type flow

Jacques Cousteau could

never get this low"

(Wu-Tang Clan – Da Mystery of Chessboxin' )

I didn't mean to demean myself ( me)

May I also take the opportunity to say that by no means would I like to ruin or rain on your intelligent/ enlightened discussion with Oga Harrow and the other serious intellectuals like yourself.

I admit that your sensitivity filter /sense of intolerance for strong words is much greater than mine, but don't you think that revulsion in this instance is too strong a word ? I shudder at what you should think about Kperogi's venom and invective that he usually hurls at those with whom he disagrees; in my lexicon such invectives are nothing as kind as the rime in this lullaby - and I do hope that I'm speaking the kind of English that both of you understand, maybe, ever so slightly, differently. I do love rap and poetry.

But I have taken note of your disgust:

Every man has his own and it's exactly the way that I feel about certain kinds of pernicious corruption, carrion flesh.

The idea of eating pork fills me

with revulsion.

As Jesus of Nazareth told some of his people (the Pharisees) who I'm sure were 100% keeping kosher, "it's not what goes into your mouth but what comes out that (also) defiles us" - i.e. evil speech.

Of course what comes out of the anus

does not defile us... (good riddance)

I don't know which words Jesus was writing in the dust when some chaps were gathering to stone to death a woman who had been "caught" in adultery.

You don't have to indulge me.

About contributing to the "enlightened debate" I did say - like an Englishman, that it is my language that you are making this great fuss about. Now if e.g. Theresa May said on the BBC "I am a native speaker of standard English "- or some other kinds of English I'm sure that there would be no fuss about that. If she had asked, "Don't you understand me? Am I not speaking good Nigerian English" - she would have probably been accused of arrogance and racism. I myself speak good English, Swenglish and many other kinds of English as some occasions demand and I'm a master of them all. A master of my own speech, my own lines - Without your permission, I proclaim here and now, like Jelly Roll Morton who said that he "invented jazz "just wait and see. I myself can be exceedingly polite - good manners were instilled in me and the rule of thumb is respect begets respect. As far as respect goes, there is nobody in this forum that I fear more than Biko Agozino - because I know (special mystical knowledge) that should I trespass against him, he can - because he has the absolute potential to repay me in kind. As Imam Ali (alaihi salaam) said , so too I'm not afraid of anyone who is not afraid of me. Why should I be? But I'm taking your objection seriously; I had thought that from henceforth I would approach Kperogi's future essays with all the vicious critical acumen that I can muster (as a wikid critic who can deep-fry any bugger) - but in spite of it all he is as much a friend as the guy in the oval office...

Here’s John Oliver going on about Obamacare

I apologise. No longer will I disturb your peace of mind. If you see me less often in this forum it's because I'm (a) studying Torah , (b) working on a story and (c) spending more time with my Spanish guitar ...

Forgive me

Now I'm outta here

Sincerely Yours,

Cornelius

Olayinka Agbetuyi

Farooq A. Kperogi

So Standard English has a shelf life. Right?

Elizabethan English was standard in its day but fell out of fashion, somewhat.

Kenneth Harrow

There’s one more factor I’d like to have farooq’s opinion about here. I had learned, way back, that the evolution of latin into the romance languages—that is the change from a single language into many different ones, passing through different dialects to languages—came about because the local regional variants became increasingly distant from each other over time. That made great sense in the past because people didn’t travel very much, they remained close to home throughout their lives, and thus as language changed locally, the neighbor’s language became increasingly remote, to the point where, I’ve been told, as late as the 19th c, if you traveled from one village to another in Italy people couldn’t understand each other.

I was born in 1943, and I can tell you the accents in the different boroughs of new York were pretty different, esp Brooklyn, which we used to imitate to make fun of it. My family was mostly the Bronx, also w strong accents

Now it’s all gone. Not only the new York accent is all flattened out, not only are there millions of non-new Yorkers who have come and amalgamated into some kind of very mild accent, the differences between the boroughs is gone.

Same here in Michigan. A trace of Midwest accent, that’s what we have. But the shift into dialects and new languages is disappearing because we all move, our kids move, and most of all there is that one accent on the radio and tv or in the movies which is very close to the same thing.

In Africa, at least in the 70s, one had the impression again that regional differences, the wolof of Dakar (called frolof) vs the village was radically different. How many variants of hausa or Yoruba were spoken in Nigeria or across the region? And now, as more people move, as the media have become more accessible, has this process of a language splitting into many different dialects and then different languages begun to abate? I know small languages disappear, but I wonder if the creation of new languages is dying.

Which takes me to English: “world” English should become a zillion different languages, so that something like pidgin should become incomprehensible to “standard” Nigerian English speakers. But is this happening? And is Nigerian English moving away from british or American English? Or does standard English, taught in the schools, published in our books, flatten out the differences and impose a uniformity on the speech and language around the world? Will indian English become radically different from Nigerian English, or will the pressures of globalization impose a uniformity on them, keeping them mutually comprehensible and merely regional variants, or even close to the same language? And I wonder whose pronunciation will win over the long run, and why?

ken

Kenneth Harrow

Dept of English and Film Studies

http://www.english.msu.edu/people/faculty/kenneth-harrow/

From: usaafricadialogue <usaafric...@googlegroups.com> on behalf of "Farooq A. Kperogi" <farooq...@gmail.com>

Reply-To: usaafricadialogue <usaafric...@googlegroups.com>

Date: Thursday 16 March 2017 at 09:48

To: usaafricadialogue <usaafric...@googlegroups.com>

Subject: Re: USA Africa Dialogue Series - “An advice, ” “a good news”: Errors of Pluralization in Nigerian English

On Thu, Mar 16, 2017 at 1:16 AM, Emeagwali, Gloria (History) <emea...@ccsu.edu> wrote:

--

Samuel Zalanga

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue@googlegroups.com

To subscribe to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue+subscribe@googlegroups.com

Current archives at http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

Early archives at http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "USA Africa Dialogue Series" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to usaafricadialogue+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

For more options, visit https://groups.google.com/d/optout.

--

Listserv moderated by Toyin Falola, University of Texas at Austin

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue@googlegroups.com

To subscribe to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue+subscribe@googlegroups.com

Current archives at http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

Early archives at http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "USA Africa Dialogue Series" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to usaafricadialogue+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

Olayinka Agbetuyi

Olayinka Agbetuyi

Kenneth Harrow

Hi Gloria

We share a common language, like Arabic, when we read it. But if someone from far off heard me, they’d quite like not understand a word I said

Cornelius Hamelberg

Dear Olayinka Agbetuyi,

Many thanks for your first intervention and more especially these your latest, very gracious comments, about which we are in complete agreement. I have just asked my mentor Ogbeni Kadiri about Ęyin l'ohùn' which he explains is like eggs, when you drop an egg you cannot re-collect / re-assemble it as a whole. The Rabbis say the same about Lashon Hara - that some words leave one's mouth or keyboard, like an arrow and when you shoot words like an arrow, you cannot recall them. According to the Talmud, "the tongue is an instrument so dangerous that it must be kept hidden from view, behind two protective walls (the mouth and teeth) to prevent its misuse."

Apart from my main man Ogbeni Kadiri I also have my grand repository of Yoruba ethics in the form of Oga Toyin Falola and Aderonke Adesola Adesanya's ETCHES ON FRESH WATER in some ways a sort of Ethics of the Fathers // Pirkei Avot

It's 16/3/2017 and you get me reminiscing some more, perhaps of some sociological significance - on the spot right here in my computer room in Enskede.

Re - concerning the many possible instances of "an African native English speaker born and raised in Africa " -

1. As was once forcefully brought to my attention by one Desmond Mcdermott an old friend in the 70's Stockholm - a Whitey from South Africa beating his chest and shouting " My Country!" - forced into exile. I was on the phone just now talking to Farooq (a South African Indian Farooq) who was explaining a little about the state of Anglo-Saxon South Africans , some of whom were bi-lingual since the Apartheid Boers had imposed their Afrikaans language on them and that there are twenty five official languages in South Africa. So, there are a lot of African native English speakers born and raised in Africa, not just Alan Paton and Brother Ezekiel Mphahlele our Nadine Gordimer and J. M. Coetzee (Afrikaaner parents) or Andre Brink - and many bilingual South Africans , jazz musicians, artists, revolutionaries whose company I have kept over many, many years...

2. As a speech analyst I can identify many kinds of diverse African accents - plus American - from Texas to Maine, various English, Australian - of course - Irish, Scottish etc. But this takes the biscuit : my friend's son Sundiata - born and raised in the South of Sweden almost shocked me out of my skin when he told me that he had not been living in the states (he sounded like Chuck D) how come , I asked him. Well , he had been listening to Cartoon Networks since he was about two days old...

3. Enter the biographical. In my case - an African born and partly raised in Africa where until the age of six, as I have said, many times, beating my chest proudly, I had acquired Fullah/ Fulani/ Peul language as my first language until the age of six when I was unceremoniously whisked off to Merry England - and to this day an eternal mystery to me how - tabula rasa - my knowledge of Fullani was completed erased from my memory, consciousness, everyday life, I believe because I no longer had any companions with whom I could speak it. I am angry about this. One of those things in life. It was only as late as 1990 something that my mother who had permanently emigrated to the UK in 1969 with my step father and my brothers Patrick and Michael - ( at which time my brother Harold had been sent packing to New York ) - and my Better Half and I had decided to continue our honeymoon in Ghana - it was only as late as that that my mother Adekumbi told me at length about the first six years of my life and a lot of other things. About the possibility of fully reacquiring Fulani apart from learning it - I have toyed with the idea of regression therapy - although I am a little apprehensive of its clinical associations and of possibly unearthing what could possibly be best not remembered. Sometimes, it's better to let sleeping dogs lie..

What is even more mysterious is how - and when - at which point I

acquired the English Language - and simultaneously at the same age

- at six - began to read, not just Winnie

the Pooh and Tales

of Sherwood Forest , but Aunt Nelly's " Woman’s

Own " (magazine) and anything else that I could lay hands

on. Aunt Nelly's women’s magazines gave me a precocious insight

into the inner workings and machinations and thought processes of the

Oyibo female mind as - much more experienced now, I understand them

even better - indeed that early childhood period coincided with my

falling in love with Miss Walsh, our school mistress (I have a faded

black and white school photograph with her standing besides us and

me sitting next to Jimmy Mannix who was my best friend then - I

remember how my heart used to beat with jealousy when the bloke who I

assumed was Miss Walsh's boyfriend, used to come to pick her up after

school and I could not understand or account for this feeling of

wanting to kick him in the shins, a feeling that almost overwhelmed

me. Charlotte and I were the only dark skinned people in the whole

school - and the rest of the school - almost the whole school (just

kidding ) - but in late winter a bunch of our classmates would be

waiting for us armed with snowballs with which to pelt us when school

was over, so we had to negotiate our way out of school, which

alternate exits to take. This was an almost daily occurrence. It was

all clean fun and of course we didn't know anything about racism

then, not even when a road worker ( repairing he road) once asked me,

" What time is it?" and I told him that I didn't know and

he asked me whether it wasn't it true that "darkies

"( Dark skinned people) could just take one look at the sun and

tell exactly what time it was ! Aunt Nelly was a stickler when it came to pronunciation - I should say paint box and not "pint box" - like an East ender - I heard that after they moved to Ikoyi - when they relocated to Nigeria, that she became personal secretary to Sir Abubakr ( could someone please confirm that?

At school - we went by bus - some of the kids used to tease Charlotte by calling her "Charlotte Cocoa". Once - the only time we set foot in a church is when some of the church people off Sinclair Road came to borrow me to play the part of one of the three wise men from the east - in the nativity play in the church. That's when In started feeling more important. About this racism thing I still vividly remember looking out of the window of the second floor of 144 and what did I see on the other side of the road but a young hooligan pulling at Charlotte's hair trying to snatch her school satchel from her ! I remember my heart pounding as I raced down the stairs crossed over the street and gave the boy the beating of his life - some karate sparks, kicks and punches. After which I think I was reported to Uncle Jess and Aunt Nelly as the greatest hooligan in the neighbourhood. It was something like Sonny's Lettah :

"soh me chuk him in the eye

and him started to cry

mi

thump one in him mout

an him started to shout

mi kick him

pan him shin

an him started to spin

mi thump him pan him

chin

an him drop pan a bin..."

Back in Sierra Leone, some transitions but simultaneously half living within the colonial expatriate community of mostly Brits, in the first form I remember it was at the morning assembly, the principal was giving his morning speech when he asked the assembly for the meaning of the word yoke - - I was in the front row so my hand shot up and I answered the question - for which the senior prefect congratulated me later - but it really wasn't a big deal - in form one we were then reading "Lorna Doone". One of my classmates was Omodele Wariboko, also Nestor-Cummings John, Richard Fairweather (English boy his father was a captain in the army) Leonard Gordon-Harris, Fowell Whitfield, Sylvester Young, Akintola Wyse (the wise) Cyril "Bamy" Sawyer, Desmond Easmon, George Morgan, Abisodun Wilson, Raymond Coulson, Ronald Dove, about ten classmates more. It was the brightest constellation of stars in the universe fully at home in the English language sphere and I doubt that any of us would be sending questions to the Kperogi column about the use of adjectives, word order, prepositions of the placing of adverbs not even in Latin at which we were all soon adepts ( in the first form Winston Forde - then in Upper sixth was giving me private lessons in Latin (said to be one of the backbones/ building bricks of the English Language - so to my consternation years later I could read articles about Islam in Latin, without much difficulty!)

It's 2102 and time for my late dinner. If You were from the Naija Delta I would be saying,

See you later alligator...

and many thanks if you were courteous enough to read this far.

As we say in Standard Swedish, Tusen tack

Cornelius

Olayinka Agbetuyi

M Buba

Prof Malami Buba

Olayinka Agbetuyi

Kenneth Harrow

Hi malami

I don’t agree with “de-linking” from English. I do agree with privileging local knowledge, but the mistake is to regard English as anchored in the cultural values of the west or the u.s. I know that is ngugi’s claim, but it is wrong. It takes languages as frozen.

Not only is English now global, delinking from the global tool that is now available to all is to delink from the body of knowledges being produced in English. That is to cut off your nose to spite your face.

I’d prefer the tutuola solution, or the pidgin solution: take possession of English and make it your own, do with it what you will, embrace the differences (which are not errors, except to those wishing to impose a dominant variety on all), and transform it. All great literatures, including English! Including irish! Including American even!! have done just that.

And so have African varieties unabashedly.

The notion that zulu or xhosa might give mda a greater, more “authentic” voice is totally wrong.

Why do I say that? Read glissant if you must ask.

Or ask nza the bird why he isn’t perching

Toyin Falola

Sent from my iPhone

Olayinka Agbetuyi

Assensoh, Akwasi B.

SIR Toyin:

Have safe and blessed travels in South Africa!

Your English is never mediocre. instead, it is very much

uncomplicated and smooth! I totally agree with what you told the people of the Sokoto Caliphate: to use Hausa; we need different forms of lingua franca all over Africa, something that Professor Wole Soyinka and other Pan-African Writers suggested years ago.

Enjoy the precolonial catalytic conference. Baba Ijebu (one of my legendary mentors) would laugh heartily at the description, "precolonial catalytic conference". To him, that would be book long! He would have asked you, SIR Toyin, if he (Baba Ijebu) needed an encyclopedia to use, to understand the title of the conference!😊

A.B. Assensoh.

Sent: Friday, March 17, 2017 12:45 PM

To: usaafric...@googlegroups.com

Olayinka Agbetuyi

Kenneth Harrow

Hi olayinka

I remember hearing/reading a long time ago that kids learn better in the mother tongues. It seems counterintuitive for any place on earth to educate their children in a foreign language. By high school age, in a country like Nigeria, or Senegal, I would make sure all kids had enough English or French instruction to be able to get jobs in those languages.

As far as a foreign country paying for instruction in another country, that is not reasonable. If you want an idealistic world, change the unequal distributions of wealth instead of asking for things that no one would do…..

On the other hand (isn’t there always another hand), the French emphasize la francophonie and pay for it in lots of ways. No one needs to pay for English, it is more desired than anything; and I noticed the Chinese are now building those Chinese studies and language centers. Lots of religions do the same, with Hebrew school, greek (for the orthodox) and Arabic.

I prefer being realistic, not idealistic, when it comes to language instruction. I would want my kid to be enabled by his or her education, meaning, let them get the languages they need.

ken

Kenneth Harrow

Dept of English and Film Studies

http://www.english.msu.edu/people/faculty/kenneth-harrow/

Farooq A. Kperogi

My own take, which I argued in Sokoto where I told them to use Hausa to teach all disciplines at the university level, is not about the ability or otherwise to use correct English but how best to access and use knowledge.

Salimonu Kadiri

I agree with you Malami Buba, that our future in Nigeria should be de-linked with English language. Nigerians speak and write standard English but, for instance, we don't have a standard hospital where our President can get treated when he is sick as it has recently been proved. Yet we have sixteen University Teaching Hospitals with personells that are verse in spoken and written standard English in Nigeria. Here follows the list of the University Teaching Hospitals in Nigeria and their appropriated budgets for 2016.

1. University of Lagos Teaching Hospital N212, 539,245

2.Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital N230, 904,995

3.University College Hospital Ibadan N230, 904,795

4.University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Enugu N218, 335,908

5.University of Benin Teaching Hospital N212, 886,502

6. Obafemi Awolowo Teaching Hospital Ile Ife N162, 622,221

7. University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital N166, 802,164

8.University of Jos Teaching Hospital N228, 717,880

9.University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital N169, 498,392

10.University of Calabar Teaching Hospital N201, 082,446

11.University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital N215, 151,873

12.Usman Dan Fodio University Teaching Hospital Sokoto N279, 000,000

13.Aminu Kano University Teaching Hospital N210, 380,376

14.Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Nnewi N166,188,931

15.University of Abuja Teaching Hospital N198,715,702

16.Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Teaching Hospital N229,005,992

Beside the above University Teaching Hospitals, there is a State House Medical Centre in Abuja which is popularly called Presidential Hospital because it is specially designed and equipped to provide medical cares for the President, Vice President, their families, staff of the State House and other entitled public servants. Total budget for Abuja's State House Medical Centre in 2016 was $16 million or N3.87billion. The standard English speaking and writing physicians at our Teaching Hospitals cannot treat our sick president not to talk of ordinary Nigerians, in spite of the money budgeted for them. The quality and usefulness of spoken and written standard English in Nigeria are seen on our roads, waterworks, Oil refineries, iron & steel industry, animal breeding, electric generation and distribution and agriculture. Standard English my foot!!

S. Kadiri

Skickat: den 17 mars 2017 10:51

Till: usaafric...@googlegroups.com

Ämne: Re: USA Africa Dialogue Series - “An advice, ” “a good news”: Errors of Pluralization in Nigerian English

M Buba

Prof Malami Buba

Farooq A. Kperogi

School of Communication & Media

Kennesaw State University

Cell: (+1) 404-573-9697

Personal website: www.farooqkperogi.com

"The nice thing about pessimism is that you are constantly being either proven right or pleasantly surprised." G. F. Will

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue@googlegroups.com

To subscribe to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue+subscribe@googlegroups.com

Current archives at http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

Early archives at http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "USA Africa Dialogue Series" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to usaafricadialogue+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

For more options, visit https://groups.google.com/d/optout.

--

Listserv moderated by Toyin Falola, University of Texas at Austin

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue@googlegroups.com

To subscribe to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue+subscribe@googlegroups.com

Current archives at http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

Early archives at http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "USA Africa Dialogue Series" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to usaafricadialogue+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

For more options, visit https://groups.google.com/d/optout.

--

Listserv moderated by Toyin Falola, University of Texas at Austin

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue@googlegroups.com

To subscribe to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue+subscribe@googlegroups.com

Current archives at http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

Early archives at http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "USA Africa Dialogue Series" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to usaafricadialogue+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

For more options, visit https://groups.google.com/d/optout.

--

Listserv moderated by Toyin Falola, University of Texas at Austin

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue@googlegroups.com

To subscribe to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue+subscribe@googlegroups.com

Current archives at http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

Early archives at http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "USA Africa Dialogue Series" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to usaafricadialogue+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

For more options, visit https://groups.google.com/d/optout.

--

Listserv moderated by Toyin Falola, University of Texas at Austin

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue@googlegroups.com

To subscribe to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue+subscribe@googlegroups.com

Current archives at http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

Early archives at http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "USA Africa Dialogue Series" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to usaafricadialogue+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

For more options, visit https://groups.google.com/d/optout.

--

Listserv moderated by Toyin Falola, University of Texas at Austin

To post to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue@googlegroups.com

To subscribe to this group, send an email to USAAfricaDialogue+subscribe@googlegroups.com

Current archives at http://groups.google.com/group/USAAfricaDialogue

Early archives at http://www.utexas.edu/conferences/africa/ads/index.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "USA Africa Dialogue Series" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to usaafricadialogue+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

Kenneth Harrow

Dear malami

There is an element of agreement perhaps we can share. I think much more important than the language is the perspective. European/western perspectives assume they are universal, and were totally autochthonous. Wrong on both counts. I don’t use the term afrocentric, but an afro-perspective is indispensable to counter the dominance of the European. Not the language.nigeria has many languages, a great advantage. You want to give up one of the key ones; instead, I’d want to take possession of it, make it Nigerian, keep it Nigerian, teach it Nigerian. Use Nigeria as the center for the language and the teaching. That’s legitimate, and positive.

The other thing is we each speak in and through the other. Europeans no less than anyone else. The more isolated we are, the less the Other is present to us, the more monotone, singular, limited, inhibited, and ignorant we become. I am dead set against notions of authenticity for that reason. The real authentic exists only with and through the Other.

Not hybridity or mixture, but a subjectivity that is partial and marked by many locations, many sites of enunciation. We inhabit multiple subjectivities. Perhaps we are ashamed of some, thing we are inferior in some regards; perhaps others make us feel superior, larger, more powerful. We deny some, are blind to some.

But I would hope we could come to accept our multiple subjectivities, and see them in more than one way.

Olayinka Agbetuyi

Olayinka Agbetuyi

Emeagwali, Gloria (History)

As far as I know, there are lots of Hausa language tapes and grammar texts, available for people to learn the language - not to mention numerous Hausa speakers.

Pedagogical exclusivism, epistemic isolationism and educational apartheid take place when you prioritize English as being the only possible language on the planet for instruction. Add to these wonderful concepts, linguistic imperialism and hegemony - of a former colonizer.

You don't have to be Hausa to speak the language, no more than you have to be Chinese to speak Chinese, as your post implies, somewhat. The same applies for all local languages. Professor Buba can choose to specialize in English- but that does not negate the essential fact that local languages, including Hausa, can be effective and desirable vehicles of instruction at various levels, along with, or, instead of, English. It is not about you or me, but about foundations for the future in terms of development and communication strategy.