Old Japanese Poems in Nihon Kōki

149 views

Skip to first unread message

Ross Bender

Oct 8, 2021, 12:07:55 PM10/8/21

to pmjs

There are twelve poems inscribed in Japanese in the court chronicle Nihon Kōki. An example is Emperor Kanmu's poem from Enryaku 20.1.4 (801). At a banquet after snow had fallen, the Emperor composed a Japanese poem. It is written in Man'yōgana. I am looking for any discussion in English of these poems.

宇米能渡那

胡飛都都隖黎叵

敷留庾岐尔

渡那可毛知流屠

於毛飛都留可毛

Ume no hana koitsutsu oreba furu yuki wo hanakamo

chiru to omoitsurukamo

Ross Bender

Or Porath

Oct 8, 2021, 1:02:33 PM10/8/21

to pm...@googlegroups.com

Dear Ross,

I haven't found much discussion of the poem, but there are several translations into English. This poem is mentioned by Jin'ichi Konishi's A History of Japanese Literature, Volume 2: The Early Middle Ages, on pages 60-61. His translation is as follows:

So Impatiently

Do I await the plum blossoms

That when snowflakes fall

I tend to mistake them for,

Petals scattering everywhere.

Konishi comments that the poem was written during a banquet and it was actually snowing that day. But that is already noted in the Nihon kōki entry. An alternative translation can be found in Sakamoto Taro's The Six National Histories of Japan. The poem is discussed from page 138 onwards:

The plum blossoms -

when in love,

I have mistaken

the fallen snow

for scattered plum blossoms

Another translation was produced in Helen Craig McCullough's Brocade by Night: ‘Kokin Wakashu’ and the Court Style in Japanese Classical Poetry, page 171:

When I broke a bough,

nostalgic for plum in bloom,

I almost thought them

flowers beginning to scatter –

those snowflakes fluttering down.

There is also a German translation in Rikkokushi, die amtlichen Reichannalen Japans Volume 1, by Horst Hammitzsch, on page 432.

I hope this is helpful.

Best,

Or Porath

--

PMJS is a forum dedicated to the study of premodern Japan.

To post to the list, email pm...@googlegroups.com

For the PMJS Terms of Use and more resources, please visit www.pmjs.org.

Contact the moderation team at mod...@pmjs.org

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "PMJS: Listserv" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to pmjs+uns...@googlegroups.com.

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/pmjs/CAMEQgpG9KRu%3DoXnpp-PbAjTu7hr07DPH16OCoGSJffPXkpDfoQ%40mail.gmail.com.

Or Porath, PhD

Postdoctoral Researcher and Instructor

Postdoctoral Researcher and Instructor

Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations

University of Chicago

University of Chicago

Alexander Vovin

Oct 8, 2021, 1:56:06 PM10/8/21

to pm...@googlegroups.com

Dear Ross et al.,

I am not aware of any English discussion, although i vaguely remember that i saw some translations.

Several notes on the man'yōgana script of the poem you presented.

1) I am not aware of other instances of the usage of

渡 for pa , and I can't think of any motivation for either ongana or kungana.

2)

黎 for re is attested only in the Nihonshoki (NS), while

叵 for pa (but never for ba, as far as I know) appears very rarely only in the MYS.

3)

庾for yu is again an exclusive NS graph

4) I trust you made a mistake on line three: it should be puru yuki ni, not puru yuki wo.

5)

屠 is yet another NS graph, not occurring normally in the man'yōgana A, and it is a graph for to, not tə.

6) the accuracy of kō-tsu distinctions is quite high: with two exceptions

屠 mentioned above, and the usage of

飛 for both pi and pï (should be only for the latter in kopï- on line two, but not for omopitutu, Naturally, I do not include

毛 for mo here, as the distinction between mo and mə was almost complete gone after the Kojiki, being only statistically preserved in the book five of the MYS.

7) The mixture of the man'yōgana A and B is a problem that cries for an explanation.

Hope this helps.

Alexander Vovin

Membre élu d'Academia Europaea

Directeur d'études, linguistique historique du Japon, de la Corée et de l'Asie centrale

ECOLE DES HAUTES ETUDES EN SCIENCES SOCIALES; Membre élu d'Academia Europaea

Directeur d'études, linguistique historique du Japon, de la Corée et de l'Asie centrale

Membre associé de CENTRE DE RECHERCHES SUR LE JAPON

Laureate of 2015 Japanese Institute for Humanities Prize for a Foreign Scholar

Editor-in-chief, series Languages of Asia, Brill

Co-editor, of International Journal of Eurasian Linguistics, Brill

PI of the ERC Advanced Project, AN ETYMOLOGICAL DICTIONARY OF THE JAPONIC LANGUAGES

105 Blvd Raspail, 75006 Parishttps://ehess.academia.edu/AlexanderVovin

Александр Запрягаев

Oct 8, 2021, 3:11:11 PM10/8/21

to PMJS: Listserv

Could 渡 be a transmission error for 波? They are quite similar graphically, and among the rapid forms of two there are many similar to each other.

Alexander Zapryagaev

пятница, 8 октября 2021 г. в 20:56:06 UTC+3, sasha...@gmail.com:

Ross Bender

Oct 8, 2021, 3:50:22 PM10/8/21

to pmjs

Well, this is all very interesting, and as Sasha comments, there is at least one problem crying for an explanation.

First of all, as Zapryagaev notes, what I transcribed as 渡 should indeed be 波. This resolves Sasha's point #1.

As to Sasha's point #4, both of my sources read this as "wo." These are Sakamoto 1970, Rikkokushi, p. 245, and Morita Tei's 2006, Nihon Kōki, Vol 1, p. 255. Both give the original with gloss.

Or Porath's three translations make me wonder if we're dealing with exactly the same poem here. The second version is actually from Brownlee's 2001 translation of Sakamoto, and it does seem a little odd -- "the plum blossoms - when in love I have mistaken." Both Morita and Sakamoto gloss "koitsutsu" as 恋いつつ, which I presume Brownlee gets his line from. But the other two versions -- "So impatiently do I await the plum blossoms" and "nostalgic for plum in bloom" make more sense to me.

The McCullough translation "When I broke a bough" makes me question whether this is a later version -- did this poem in fact make it into Kokinshū? And in this form? Because there's absolutely nothing in the poem or the preface to suggest that Kanmu broke a bough.

At any rate, what surprised me here was to find this and other Japanese poems in Nihon Kōki, which is inscribed in classical Chinese but includes a good number of OJ senmyō. But the Japanese poems, at least this one, are done in a weird form of Man'yōgana. So does this mark an important transition? Donald Keene, in Seeds in the Heart, has an entire chapter on "The Transition from the Man'yōshu to the Kokinshū." He comments "The ninth century has often been described as a 'dark age' of poetry in Japanese." (p.221) Keene discusses the Shinsen Man'yōshu from this period, noting that "The waka in the Shinsen Man'yōshu were transcribed in the archaic Man'yōgana, though this was done barely a dozen years before the compilation of the Kokinshū, in which the poems were all given in hiragana."

Interestingly the one poem Keene gives from the Shinsen MYS also concerns plum blossoms: "If only I had merely watched as they fell -- the plum blossoms -- but, alas, their fragrance lingers still on my sleeve."

Ross Bender

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/pmjs/aed14796-a52f-4e55-b529-facbf8d894a2n%40googlegroups.com.

Chris Kern

Oct 8, 2021, 4:23:22 PM10/8/21

to pm...@googlegroups.com

Dear Ross,

I just searched the 新編国歌大観 and could not find any other sources for this poem (although there could be textual variations). My guess is that McCullough interpreted

隖黎叵 as 折れば rather than 居れば. There's often uncertainty in the commentary tradition about whether there is a play on words between these two, or which one it is when おれば or をれば appears in hiragana.

Sincerely,

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/pmjs/CAMEQgpHrXYzdw5%3D_1gDDVMFtqPZy4Qha%2B06dR-ydoCoY2GwYWw%40mail.gmail.com.

Richard Bowring

Oct 8, 2021, 4:23:31 PM10/8/21

to pm...@googlegroups.com

Ross.

McCullouch is quoting an example from Michizane’s Ruijū Kokushi.

But I am perplexed. If “oreba” does not mean break off, what do you think it means?

Richard Bowring

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/pmjs/CAMEQgpHrXYzdw5%3D_1gDDVMFtqPZy4Qha%2B06dR-ydoCoY2GwYWw%40mail.gmail.com.

Alexander Vovin

Oct 9, 2021, 3:27:49 PM10/9/21

to pm...@googlegroups.com

Theoretically, everything is possible. You might be right, but I see the following obstacles:

1. Official histories, as far as I know, were written in the 楷書, but not in 草書 or 行書 (Ross pls correct me if I am wrong), therefore it is more difficult to confuse 波 with 渡.

2. Scribal substitution errors normally occur in the direction graphically more complex > graphically simpler. Not the other way around.

3. Substitution is the weakest possible explanation. Therefore, it should be the last resort.

This should answer Ross's point #1.

About the point #2:

尔 always stands for /ni/, never for /wo/. One of your secondary sources made a mistake, and it was perpetuated by others.

On woreba/oreba problem. As Richard pointed out the context calls for oreba being written

隖黎叵

. But we have another problem here. 隖 must be a man'yōgana B sign, cf. 嗚 or 塢, but it is not attested per se in the Nihonshoki and appears to be unique. The only solution that I can think of at the moment is the merger of /o/ with /wo/ = /wo/. But 800 is still too early for that. Ross, what is the date of the first Nihon kōki manuscript.

Alexander Vovin

Membre élu d'Academia Europaea

Directeur d'études, linguistique historique du Japon, de la Corée et de l'Asie centrale

ECOLE DES HAUTES ETUDES EN SCIENCES SOCIALES; Membre élu d'Academia Europaea

Directeur d'études, linguistique historique du Japon, de la Corée et de l'Asie centrale

CENTRE DE RECHERCHES LINGUISTIQUES SUR L'ASIE ORIENTALE

Membre associé de CENTRE DE RECHERCHES SUR LE JAPON

Laureate of 2015 Japanese Institute for Humanities Prize for a Foreign Scholar

Editor-in-chief, series Languages of Asia, Brill

Co-editor, of International Journal of Eurasian Linguistics, Brill

PI of the ERC Advanced Project, AN ETYMOLOGICAL DICTIONARY OF THE JAPONIC LANGUAGES

105 Blvd Raspail, 75006 ParisTo view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/pmjs/aed14796-a52f-4e55-b529-facbf8d894a2n%40googlegroups.com.

Robert Borgen

Oct 9, 2021, 3:27:56 PM10/9/21

to 'kktroost@me.com' via PMJS: Listserv

Ross,

You mention that Nihon Kōki includes twelve poems in Japanese. Does this mean poems only from the surviving chapters? At least one waka, presumably from one of the lost chapters, is preserved in Nihon Kiryaku. You can a translation of it in my article, "The Japanese Mission to China 801-806 (MN 37, Spring 1982). Like the one you cite, it was by Kanmu himself. A hurried search of online sources didn't produce an examples of kanshi by Kanmu. Maybe compilers of Nihon Kōki included some of his waka because he wasn't very good at composing kanshi?

Robert Borgen

> To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/pmjs/4E1C9647-CE67-40B4-B9E9-E79D3EBB9B68%40cam.ac.uk.

You mention that Nihon Kōki includes twelve poems in Japanese. Does this mean poems only from the surviving chapters? At least one waka, presumably from one of the lost chapters, is preserved in Nihon Kiryaku. You can a translation of it in my article, "The Japanese Mission to China 801-806 (MN 37, Spring 1982). Like the one you cite, it was by Kanmu himself. A hurried search of online sources didn't produce an examples of kanshi by Kanmu. Maybe compilers of Nihon Kōki included some of his waka because he wasn't very good at composing kanshi?

Robert Borgen

Ross Bender

Oct 9, 2021, 9:07:22 PM10/9/21

to pmjs

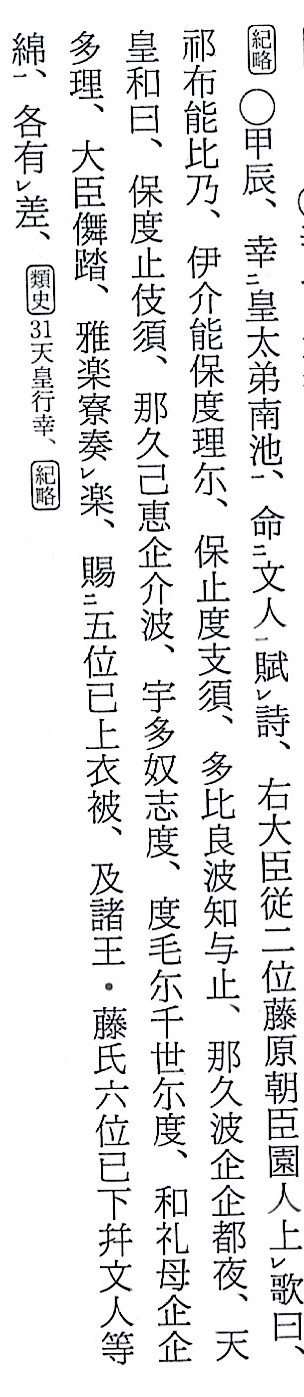

I am enclosing/attaching the poem in its context, from Morita Tei's edition of Nihon Kōki, p. 254. Hopefully this will settle some of the issues being raised. My mistake was in transcribing 尔. As seen in the original it is /wo/. Also in the original /pa/ is 波.

A major problem with Nihon Kōki is that only ten volumes of the original survived, and in modern editions they are supplemented with Ruijū Kokushi and Nihon Kiryaku to make the complete 40 volumes. In the image attached we see that both are cited for this poem. The conventional date for Ruijū Kokushi is 892; it was an immense topical compilation of the Six National Histories by Sugawara no Michizane.Nihon Kiryaku apparently dates from the late eleventh century, although details of its compilation are still hazy.

IMHO the Konishi translation provided by Porath is the best. The banquet was held in the winter, January of 801, and there was snow, but no reference to plum boughs or breaking branches.

Again, I think Donald Keene's comments are most helpful here. We are obviously in a transition period where waka are being inscribed in Man'yōgana. Whether this was truly a 'dark age' for Japanese poetry is questionable. BTW the Shinsen Man'yōshu includes poems both in Man'yōgana and in Chinese -- thus waka and kanshi both. Another question, and this is for Sasha, is whether this poem is Old Japanese, Early Middle Japanese, or something else.

If I have time, I will provide two more examples of this type of waka from Nihon Kōki.

Ross Bender

Ross Bender

Oct 9, 2021, 9:08:58 PM10/9/21

to pmjs

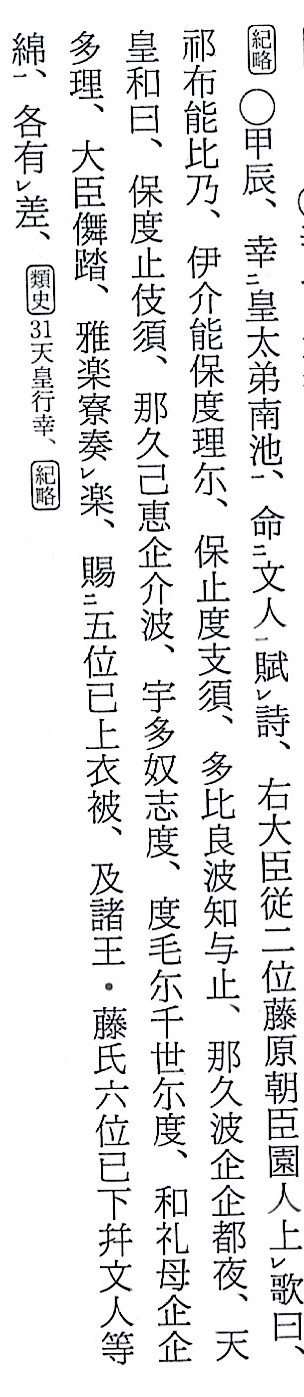

Here are two more waka from Nihon Kōki (Morita Tei, 2006, vol.2) - pp. 312-13. The date is Kōnin 4.4.22 (May 25, 813).. Emperor Saga commanded the literati to compose Chinese poems. However, Fujiwara no Sonohito (Sonondo) presented a waka, and the Emperor responded.

Transliteration from Brownlee's translation of Sakamoto 2001, p. 138:

Kyo no hi no ike no hotori ni hototogisu taira no chiyo to naku kikitsuya.

Hototogisu naku koe kikeba utanushi to tomo ni chiyo ni to ware mo kikitari.

Ross Bender

Or Porath

Oct 9, 2021, 10:26:39 PM10/9/21

to pm...@googlegroups.com

Dear Ross,

For the two poems you've just raised there are also translations and transliterations by Konishi:

Kyō no hi no on this very day

Ike no hotori ni As we gather by the lake,

Hototogisu Hototogisu sing,

Taira no chiyo to "A peaceful rule forever more!"—

Naku wa kikitsu ya. Did this reach our sovereign's ear?

Saga's reply is as follows:

Hototogisu The Hototogisu—

Naku koe kikeba As I listened to its song,

Utanushi to I heard this as well:

Tomo ni chiyo ni to "May the poet's line sustain

ware mo kikitari. The sovereign's rule forevermore!"

Note that these translations are from Ruijū Kokushi, 31:172.

Best,

--

PMJS is a forum dedicated to the study of premodern Japan.

To post to the list, email pm...@googlegroups.com

For the PMJS Terms of Use and more resources, please visit www.pmjs.org.

Contact the moderation team at mod...@pmjs.org

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "PMJS: Listserv" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to pmjs+uns...@googlegroups.com.

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/pmjs/CAMEQgpHdXm%3DztfjT7amakzj5OGUVThgmeLkFLZ1R-VBBVaD8bA%40mail.gmail.com.

Richard Bowring

Oct 10, 2021, 12:28:14 PM10/10/21

to pm...@googlegroups.com

Dear Ross.

Just to note that, strictly speaking, the translations are not by Konishi but by the translator(s) of the book, Nicholas Teele?.

I don’t think it matters that there was no reference to breaking branches in the prose. This is not a

kotobagaki in a chokusenshū, and in any case breaking off plum blossoms was such a common topos, it hardly needs mentioning. Note that Shinsen Man’yōshū is rather special because the

kanshi and waka are linked pairs (and extremely interesting in their own right).

The man’yōgana usage is presumably that of the

Nihon kiryaku scribe, so it is not surprising that Sasha would notice some oddities.

Richard Bowring

On 10 Oct 2021, at 00:31, Ross Bender <rosslyn...@gmail.com> wrote:

I am enclosing/attaching the poem in its context, from Morita Tei's edition of Nihon Kōki, p. 254. Hopefully this will settle some of the issues being raised. My mistake was in transcribing 尔. As seen in the original it is /wo/. Also in the original /pa/ is 波.

A major problem with Nihon Kōki is that only ten volumes of the original survived, and in modern editions they are supplemented with Ruijū Kokushi and Nihon Kiryaku to make the complete 40 volumes. In the image attached we see that both are cited for this poem. The conventional date for Ruijū Kokushi is 892; it was an immense topical compilation of the Six National Histories by Sugawara no Michizane.Nihon Kiryaku apparently dates from the late eleventh century, although details of its compilation are still hazy.

IMHO the Konishi translation provided by Porath is the best. The banquet was held in the winter, January of 801, and there was snow, but no reference to plum boughs or breaking branches.

Again, I think Donald Keene's comments are most helpful here. We are obviously in a transition period where waka are being inscribed in Man'yōgana. Whether this was truly a 'dark age' for Japanese poetry is questionable. BTW the Shinsen Man'yōshu includes poems both in Man'yōgana and in Chinese -- thus waka and kanshi both. Another question, and this is for Sasha, is whether this poem is Old Japanese, Early Middle Japanese, or something else.

If I have time, I will provide two more examples of this type of waka from Nihon Kōki.

<OJ poem in Nihon Koki.jpg>

Ross Bender

On Sat, Oct 9, 2021 at 3:27 PM 'Robert Borgen' via PMJS: Listserv <pm...@googlegroups.com> wrote:

Ross,

You mention that Nihon Kōki includes twelve poems in Japanese. Does this mean poems only from the surviving chapters? At least one waka, presumably from one of the lost chapters, is preserved in Nihon Kiryaku. You can a translation of it in my article, "The Japanese Mission to China 801-806 (MN 37, Spring 1982). Like the one you cite, it was by Kanmu himself. A hurried search of online sources didn't produce an examples of kanshi by Kanmu. Maybe compilers of Nihon Kōki included some of his waka because he wasn't very good at composing kanshi?

Robert Borgen

--

PMJS is a forum dedicated to the study of premodern Japan.

To post to the list, email pm...@googlegroups.com

For the PMJS Terms of Use and more resources, please visit www.pmjs.org.

Contact the moderation team at mod...@pmjs.org

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "PMJS: Listserv" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to pmjs+uns...@googlegroups.com.

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/pmjs/CAMEQgpGisQeD%2BOqN1Ps8TUM%3DvE2xHWKWVy1iib76XS_3pod8_A%40mail.gmail.com.

Alexander Vovin

Oct 10, 2021, 12:29:47 PM10/10/21

to pm...@googlegroups.com

Dear Ross,

So you were the bad scribe who made these mistakes!🙂

As for your question, since the merger of initial /o/ and /wo/ has already occurred (and 892 AD is about the time), it should be Middle Japanese (never happens in WOJ). But we do not see other typical MJ developments like -p- > -w-, for example, so it must be transitional. But the data are limited. In addition, poetry tends to be conservative. Kokinwakashū, for example, still has a lot of OJ morphosyntactic features, but its phonology is almost completely MJ (with the exception of the preservation of kō-otsu just for ko and kə - normally blissfully ignored in modern editions, but you still can see it in some old manuscripts). Hope this helps,

Sasha

Alexander Vovin

Membre élu d'Academia Europaea

Directeur d'études, linguistique historique du Japon, de la Corée et de l'Asie centrale

Membre associé de CENTRE DE RECHERCHES SUR LE JAPON

Laureate of 2015 Japanese Institute for Humanities Prize for a Foreign Scholar

Editor-in-chief, series Languages of Asia, Brill

Co-editor, of International Journal of Eurasian Linguistics, Brill

PI of the ERC Advanced Project, AN ETYMOLOGICAL DICTIONARY OF THE JAPONIC LANGUAGES

105 Blvd Raspail, 75006 Parishttps://ehess.academia.edu/AlexanderVovin

--

PMJS is a forum dedicated to the study of premodern Japan.

To post to the list, email pm...@googlegroups.com

For the PMJS Terms of Use and more resources, please visit www.pmjs.org.

Contact the moderation team at mod...@pmjs.org

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "PMJS: Listserv" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to pmjs+uns...@googlegroups.com.

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/pmjs/CAMEQgpGisQeD%2BOqN1Ps8TUM%3DvE2xHWKWVy1iib76XS_3pod8_A%40mail.gmail.com.

Reply all

Reply to author

Forward

0 new messages