Adobe is Bad for Open Government

Gabriela Schneider

I think this group, in particular, would have a lot to say about Adobe's recent Open Government PR campaign. (Are buses in your neighborhoods also wrapped in their ads? I cringe whenever I have to use the Metro Center metro stop in DC.) Clay Johnson of Sunlight has an insightful post on the Sunlight Labs blog. Curious to get your take.

http://sunlightlabs.com/blog/2009/adobe-bad-open-government/

--

Gabriela Schneider

Communications Director

Sunlight Foundation

1818 N Street, NW Suite 410

WDC 20036

p: 202/742-1520 x 236

c: 202/746-0439

gschn...@sunlightfoundation.com

http://sunlightfoundation.com

http://twitter.com/stereogab

Jones, Tom (Commerce)

I read this and I agree that the way that PDFs are disclosed is crappy. Earmark letters are my personal hobby horse.

What’s the solution or alternative though (at least for us up here on the hill.) There are a couple issues that I see as problematic and need thoughtful ways of being addressed.

Seems the consensus is that PDFs are hard to parse and get out.

I assume life would be easier with the XML. From what I understand from the guys in leg counsel is that whatever they use to draft in, generates an XML file which they then turn into a PDF and send to us. Would making that XML available with the PDF be helpful. Does that solve the problem for leg text that is not hand annotated?

One of the other issues that folks will raise – and it’s not an illegitimate issue – is that often times folks literally print out the bill and read through it and often initial changes or agreements or make handwritten corrections before the bill is rushed to the floor (ignoring for the time-being the huge problems with rushing bills to the floor) can you create a process where this is done electronically so that when folks change a dollar value in a bill they do it electronically and sign off on it electronically so that it’s out there in an easily and quickly digestible format, not a bunch of scanned pictures of pages?

I don’t really care one way or another about Adobe, but I would like to know how the process of making legislation available works in an ideal world.

Jon Henke

John Wonderlich

You could simulate the wiki you suggest by looking at any bill's progress through THOMAS, where each stage has a corresponding sponsor, or reporting committee, or amendment author.

(The exception to this are raises to the debt limit, which are automatically drafted in bill form by the Clerk of the House, and submitted without a sponsor, in a genius maneuvre of accountability evasion.)

Jones, Tom (Commerce)

Well - because that’s not how the process works. Nor really is it how it should work.

Often case staff is working on stuff as they go along, presenting options to their members and looking for their agreement on whether or not that’s the direction they want to go with the legislation. I’ve had any number of stupid ideas that we knocked down during the process. Members and staff need the flexibility to be able to draft stuff and present and discuss ideas without the whole world commenting on it.

There needs to be control and a high degree of security to the process. A wiki that everyone can tinker with isn’t really feasible when you’re talking about documents that will infringe on people’s life, liberty, and/or property.

kathy and ernie brandon

In a time of universal deceit, telling the truth becomes a revolutionary act.

-Orwell

Jones, Tom (Commerce)

What I want to know if how can we make that which is public – but opaque because of technological barriers or anachronistic traditions – more available to the public.

I’m interested in questions like:

Is it technologically feasible to do a mark-up without pens and paper and have laptops at every seat on the dais and have electronic versions of amendments before the members? If it is, it is presumably pretty easy to make that info available after disposition of the question. Are members votes tallied electronically? How do we authenticate the actions of the members? Is something like this being done somewhere already?

Jon Henke

John Wonderlich

This would be one thing to require of executive branch employees, in narrowly defined circumstances (like contract negotiations), but another for legislative deliberations.

Jon Henke

John Wonderlich

In what sense should amendments be publicly trackable that they aren't now?

Obviously there's room for improvement; the Senate's amendment tracking system should have a public component, and structured data like leg counsel's XML would go a long way too.

Beyond those incremental improvements, it still strikes me that there is either a) a clear requirement for publicness that accompanies real legislative acts, or b) an informal act that defies easy regulation.

It seems to me that all that's left between the two are incremental publishing improvements moving toward structured data published as soon as the official document is created.

Josh Tauberer

> I assume life would be easier with the XML. From what I understand

> from the guys in leg counsel is that whatever they use to draft in,

> generates an XML file which they then turn into a PDF and send to us.

> Would making that XML available with the PDF be helpful. Does that

> solve the problem for leg text that is not hand annotated?

For versions of bills printed through GPO that were originally drafted

as XML, we are already getting the XML.

When there are publicly and widely circulating unofficial drafts, as

there were for e.g. the stimulus bill a year ago, having the source XML

would be greatly beneficial over the PDF alone.

Government has a responsibility to issue print-ready documents in many

cases, so PDFs are an important part of an open government. I would

rather have PDFs over nothing electronic, over electronic image files,

and over other formats suitable for printing --- PDF is an open standard

(albeit proprietary).

I wouldn't want to get rid of PDFs. Docs need to either be published in

a second format, or --- more interesting --- we could get Adobe to

revise the PDF format so that it can encode the document in structured

form as well. That means govt publishes a single file that makes

everyone happy.

On 10/28/2009 03:36 PM, Jones, Tom (Commerce) wrote:

> What I want to know if how can we make that which is public – but

> opaque Is it technologically feasible to do a mark-up without pens

> and paper and have laptops at every seat on the dais and have

> electronic versions of amendments before the members?

It is certainly possible. Just think of Google Docs. Not for it being a

public thing, but that it supports multiple people editing a single

document with changes being tracked.

The tension between having private drafts and a public-facing system is

also solvable. The software that lets you make changes to drafts could

be made to operate in a "detached" mode so that the drafts are private

to an office --- but if you want to make any of the drafts public, e.g.

submitting them as an amendment to the clerk, the software would send

your internal draft into the clerk's system, and from there into the

public-facing system.

It's all doable, and for less than the cost of the recovery website, I'm

sure.

If a Member asks the community to build a demo system, I am sure someone

would try.

- Josh Tauberer

- CivicImpulse / GovTrack.us

http://razor.occams.info | http://www.govtrack.us |

http://www.civicimpulse.com

"Yields falsehood when preceded by its quotation! Yields

falsehood when preceded by its quotation!" Achilles to

Tortoise (in "Godel, Escher, Bach" by Douglas Hofstadter)

Michael Stern

I am not qualified to answer Tom’s questions, but I understand there is going to be an “e-Parliament” taking place on Capitol Hill next month, with representatives from legislatures around the world. Maybe that would be a good opportunity to glean best practices on these matters.

Mike Stern

Aron

pulled?

On Oct 28, 2:47 pm, Gabriela Schneider

> Hi everyone,

> I think this group, in particular, would have a lot to say about Adobe's

> recent Open Government PR campaign. (Are buses in your neighborhoods also

> wrapped in their ads? I cringe whenever I have to use the Metro Center metro

> stop in DC.) Clay Johnson of Sunlight has an insightful post on the Sunlight

> Labs blog. Curious to get your take.

>

> http://sunlightlabs.com/blog/2009/adobe-bad-open-government/

>

> --

> Gabriela Schneider

> Communications Director

> Sunlight Foundation

> 1818 N Street, NW Suite 410

> WDC 20036

> p: 202/742-1520 x 236

> c: 202/746-0439

Gabriela Schneider

yesterday--don't think this was pulled. Will look into this and post

back.

Gabriela Schneider

yesterday--don't think this was pulled. Will look into this and post

back.

On Thursday, October 29, 2009, Aron <aronpi...@gmail.com> wrote:

>

David James

Gabriela Schneider

I'm enjoying the conversation here!

I just checked, and the blog post is still there :)

J.H. Snider

John and Jon, there is a rich intermediate position between informal and formal legislation: give individual members the option to make their informal legislation formal and public. Specifically, individual members as individual members often lack the option to make their informal legislation public as part of regular parliamentary procedure. Parliamentary procedure is controlled by the majority and the majority can shut out the minority from the formal, public record. (For example, closed rules can prevent amendments from being introduced on the floor.) In other words, we need to bring a First Amendment mindset to parliamentary procedure. The majority shouldn’t be able to close down the right of the minority to enter into the public record (and embarrass the majority) in an easily accessible way. This was tolerable when parliamentary procedure had to be conducted face-to-face and attention was scarce. (For example, floor time is very precious.) But with today’s asynchronous information technology, the violation of First Amendment norms, which is part-and-parcel of meaningful open government, should no longer be tolerable. This gets to the larger problem that our current parliamentary procedure (which determines what is said, written, voted upon, and part of the public record) is antediluvian and inappropriate to a semantic Web world.

--J.H. Snider

iSolon.org

Jones, Tom (Commerce)

As a member of the minority I hate closed rules and filling the tree as much - probably more - than the next guy. But if my boss wants to file an amendment to a bill he can and will do it. He'll talk on the floor about it as much as he wants. It'll be made part of the official record. I can't begin to recall all the amendments I've worked on. They all get a number and you can go read about and review all of them. House guys can file their amendments until the cows come home. Even if the rule doesn't make them in order they can take to the floor and speak about them at night. If anything youtube etc. Has made the opportunity to get the word out on a random issue even greater.

Will all our amendments get a vote? No. But that's because for a long time my party sucked and we lost the faith of the American people. Doesn't mean Harry Reid should fill the tree and cloture us out all the time -- but we'll fix that problem at the ballot box.

From: openhous...@googlegroups.com <openhous...@googlegroups.com>

To: openhous...@googlegroups.com <openhous...@googlegroups.com>

Sent: Thu Oct 29 20:53:01 2009

Subject: [openhouseproject] On the distinction between informal and formal legislation

J.H. Snider

Tom, I’d like to clarify four points.

First, by minority I don’t necessarily mean minority party; I simply mean any member in the minority. There are more protections for minority party than individual member speech rights. For example, a member who disagrees with both the majority and minority parties has very limited ability to speak on the floor when a particular bill is up for discussion. (Two useful books on the limits of minority legislative rights are Mann and Ornstein’s Broken Branch and Binder’s Minority Rights, Majority Rule. But like you, they focus on minority party rights rather than minority member rights more generally.)

Second, I was careful to qualify my comment by saying “in an easily accessible way.” Sure, members can use the floor to speak about what they want when barely anyone is listening. But this speech isn’t linked on Thomas to the official record of a bill. It thus suffers from a significant degree of practical obscurity. With today’s technology, it is easy to link these various parts of the legislative record into one seamless whole. But the Congressional interface to display this information doesn’t do that. An analogy about the importance of practical obscurity is the difference between making member votes available by individual member vs. bill. Sure, it’s possible to reconfigure voting records by bill into voting records by member, but it is a hassle to do. This hassle has great political salience, which is why the great majority of legislatures make voting records available by bill but strongly resist doing so by individual member.

Third, we seem to be in agreement that a minority cannot put votes on the official record, although I would clarify that I’m including individual members of both parties as part of my definition of a “minority.” Member X can introduce a bill or amendment, but he cannot get a vote on it unless the leadership allows him to. But as long as voting is voluntary, why shouldn’t he be able to get a vote and put it in the official record? For example, as long as the majority party or any other majority coalition is free to ignore a vote, why shouldn’t the minority party be able to vote on an amendment and put the result in the official legislative record? The point is that such voting would help public transparency and accountability, even if the legislation had no chance of passing.

Fourth, I would staunchly oppose the view that winners in democratic elections have a right to dictate the speech rights of minorities. Fear of such “tyranny of the majority” is why we have the First Amendment and why minority rights are embedded in the U.S. Constitution and in every liberal democracy. Currently, democratic practice makes an exception for legislative speech, where we give far too much power (although certainly not absolute power) to the majority. That was okay when the only practical form of speech was synchronous (face-to-face), but it is increasingly unacceptable in the emerging information environment, where asynchronous speech should be allowed to play an increasing part.

I suspect that many others share your perspectives. Thank you for offering me the opportunity to engage in this discussion.

Soren Dayton

Imagine a blog run by the conference that just had statements on bills. It could have tags for the bill # and the member and maybe the state. Any decent off-the-shelf CMS would provide a feed to match the tag(s).

I should point out House history. Prior to the 1890s (I think) the main difference in debate between the House and the Senate were germaineness rules and the 5 minute rule versus the Senate's unlimited speaking time. During the 1890s, they introduced structured rules, which became the precedent that led to closed rules.

But the House operated for over 100 years with face-to-face interactions and no closed rules.

This is just tyranny of the majority. That's all it is. They don't want to be embarrassed.

Jones, Tom (Commerce)

At the risk of belabor this issue – I’ll respond to a couple things here

Point one – great - draw minority any way you want. I’m a member of the minority party and in my work on earmarks a member of a minority view. Re: right to speak….In the Senate again, you’re just plain wrong. My boss can and has repeatedly gone to the floor and spoken on earmarks. He’s never needed the permission of the leadership and I’m fairly confident we’ve not made a lot of friends fighting earmarks…at least within the chamber. We’ve lost repeatedly, but them the lumps.

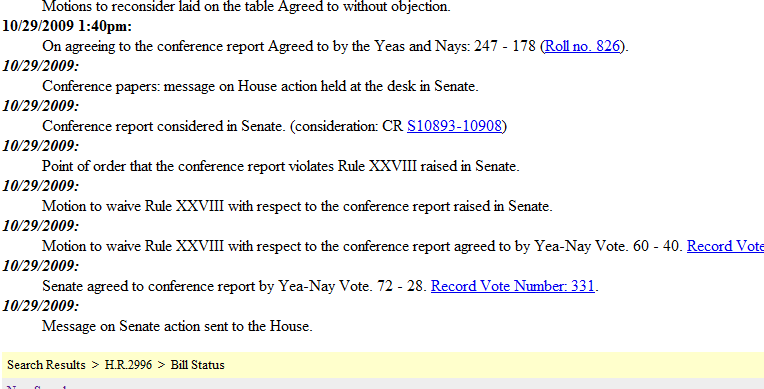

Re: linked to Thomas: I find Thomas very easy to use. Finding

this link to the CR/Interior bill we were considering yesterday took me less

than 2 minutes.

Your third point doesn’t make any sense. Yes there are closed rules. I don’t like them, but they’re a function of a vote.

This statement makes no sense to me “But as long as voting is voluntary, why shouldn’t he be able to get a vote and put it in the official record? For example, as long as the majority party or any other majority coalition is free to ignore a vote, why shouldn’t the minority party be able to vote on an amendment and put the result in the official legislative record? “ Voting is how we make laws it has consequences. It’s not there to make a point, its there to change the law of the land. If someone wants to show support for something they can cosponsor it or just submit a nice comment for the record about it.

Your fourth point is just stupid. No one is infringing anyone’s free speech right. Every knucklehead holding public office or otherwise can mouth off for as long as they want on whatever idiocy they want. If they hold an election certificate they can do it on the floor of the House or Senate (watch the house floor at about 10 pm on a weeknight – love me some special orders) . They can speak all they want. If they’re persuasive, they might win a vote.

J.H. Snider

I don’t think we’re quite at the point of belaboring the issue because some of these issues are subtle and run contrary to widely held perceptions.

First, much of my argument rests on the distinction between public information and what is meaningfully public—or, more generally, what the ideal for open government should be. This, for example, is at the core of the debate we have been having about Adobe’s endorsement of pdfs as an open government standard. Yes, public documents online in a pdf format are better than no documents online. But we shouldn’t settle for that because providing the data in a downloadable structured format (as well as in a slick report format) can do a much better job of enhancing democracy. From my perspective, then, your listing below of roll call votes on legislation is akin to posting data in a pdf format. Roll call votes in Thomas have historically been made easily accessible by bill, not by member—and we should be very careful not to conflate the two formats. Similarly, the right to speak on the record is very different when it is linked to the legislation. In my research of Congress and the 99 state legislative branches, I didn’t see a single legislative website where the bill tracking systems were explicitly linked to member statements about the bills. It’s as if member statements and bills live in two different universes. Technically, this is a trivial problem to solve. Legislatures haven’t solved it, in my opinion, because legislators want maximum control over how their statements are made accessible just as they want maximum control over how their votes are made accessible.

From my perspective, closed rules cannot be justified per se just because the majority votes for them. To me, that’s like saying that a legitimate, majority elected government should be able to shut down a newspaper or an assembly of citizens that disagrees with the government. In that context, we would all recognize the critical importance of protecting the media’s and the citizenry’s free speech rights. There is a cost/benefit equation to estimate when designing free speech rights, and I would argue that new technology is rapidly changing that equation and that those changes should be recognized in parliamentary procedure. Specifically, I would argue that a majority has very reasonable grounds to control symmetric/face-to-face type speech but not asymmetric speech. The CRS has a report on parliamentary procedure that explains why the majority has to be able to control and censor minority speech if a parliamentary body is to operate efficiently. But the CRS report also assumes that parliamentary procedure has to be based on face-to-face communications and the use of scarce floor time. In a digital world, floor time needn’t be scarce and thus should be freer of majority control. Let’s the users do the filtering of what they don’t want to hear.

You say: “Voting is how we make laws it has consequences. It’s not there to make a point, its there to change the law of the land. If someone wants to show support for something they can cosponsor it or just submit a nice comment for the record about it.” I would agree that the ostensible function of voting is to make laws. But I would argue—and I cannot understand how any student of legislative procedure would find this controversial—that a major function of voting is for communications. Indeed, a primary reason why majorities don’t let minorities introduce legislation for a vote is that the majorities don’t want to have to take a vote on a controversial position. And the reason minorities like to seek votes on legislation which has no chance of passing is for exactly the same reason. Votes, then, intrinsically convey a lot of accountability forcing information whether or not the bills to which they refer have any chance of passing. Indeed, the very reason we have votes at the deepest level, from the standpoint of democratic theory, is to convey information so we can hold elected officials accountable. We should design parliamentary procedure so there were fewer crappy votes that convey virtually no accountability forcing information. And the best way to do this, in my opinion, is to enhance minority members’ right to enter votes into the public record. Note that I’m not suggesting that majorities should have to vote on minority introduced legislation, only that the minority should be able to enter whatever votes they can get in the official legislative record. If the voters aren’t interested in such votes, leave it up to them to filte4r them out.

Lastly, every knucklehead (to use your phrase) can speak on the public record at designated times, but every knucklehead cannot speak on the public record at the critical time when speech would be most effective and politically costly (e.g., a floor speech at 4pm before the evening TV news may be much more valuable than a floor speech at 10pm when the day’s news reports have all been written). Nor, as I argued above, should all forms of public speech be conflated because the nature of public access to that speech is crucial. Consider markup hearings. That speech is officially public (the public is generally allowed to attend the hearings), but I once had my laptop confiscated by a guard when I attempted to use it to record this type of so-called public hearing speech. Why? Because Congress doesn’t want this type of speech to be too easily accessible. Again, we’re back to the political logic of practical obscurity. There are different degrees of public, and the distinctions matter a lot.

Josh Tauberer

Kevin Lyons, who works for the Nebraska legislature, wrote up some

guidelines for PDF in government, which seemed relevant:

http://wiki.opengovdata.org/index.php?title=The_good_and_the_bad_of_PDFs

Josh