Idea reviews: geometric multiplication, modulo multiplication groups, carousel models. Please respond with your thoughts!

Maria Droujkova

Please let us know what you think about ideas below.

Peter McLoughlin worked out a way to develop multiplication of real numbers rigorously without Cauchy sequences. He uses Euclid's axioms instead. We had a little "GeoGebra party" with teens and made applets based on Peter's article. Daniel Chiquito just blogged about it here: http://www.equalis.com/members/blog_view.asp?id=565749&post=125029

Kirby Utner blogs about modulo multiplication groups (with veggies) here: http://www.4dsolutions.net/ocn/flash/group.html

Mike South explores a similar idea, but instead of abstract multiplication table, his is based on combinations of transformations: http://fulcrum.org/

Levshin and Alexandrova published "The Black Mask from Al-Jabr" (in Russian) in 1967, and I translated a chapter from it about the carousel model. You can find (and edit, if you have time) the translation, and one parent's story of using it, here: http://naturalmath.wikispaces.com/Imaginary+numbers+for+young+kids

Raymond Faber sketched another rotation-based ("polar") model here: http://naturalmath.wikispaces.com/Multiply+signed+numbers

All these models have something small in common: they explain why negative times negative is positive really, really well.

And now I am going to paste everything into this email, for your convenience!

~*~*~*~*~*Daniel's review of Peter's system

The paper attempts (and succeeds) at defining the simple rules of multiplication in a simple way. Apparently, the conventional method invokes some complicated stuff, like Cauchy sequences and Dedenkind cuts, which quite frankly flies right over my head. Mr. McLoughlin's method uses only Euclid's axioms, which are arguably much simpler.

- Let the two numbers being multiplied be A and B. Let the answer (A*B) be C.

- Set up a triangle with vertices at (0, 0), (0, 1), (B, 0)

- Draw a line from point (0, A) parallel to the hypotenuse of the triangle.

- The X intercept of this line is equal to (A * B).

As an aside, this method works when multiplying two negative numbers as well:

That 1 still bothered me, though, so I included that in the formula as well (call it N). Turns out that C = AB/N. There is also provision for division in this wonderful construction!

Sadly, my contribution was completely misguided: Using similar triangles involves using multiplication, so my proof didn't contribute much. Still, It's comforting to know that I still knew what was going on up to that point. Credit, of course, goes to the author of the paper, Peter Mcloughlin, and Maria Droujkova, who introduced me to it. GeoGebra was used for the illustrations.~*~*~*~*~*Kirby's blog post (sans the flash interactive)

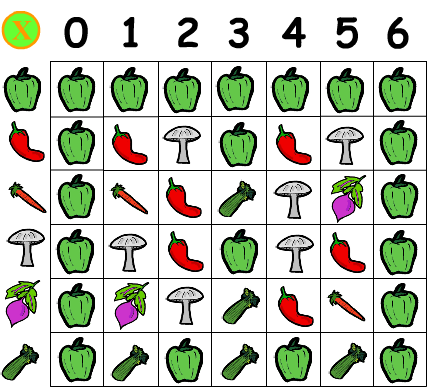

This vegetables table is isomorphic to the modulo multiplication group Z(6), i.e. the six totatives of 7 multiplied modulo 7. carrot x carrot = chili pepper just as (3 x 3) modulo 7 = 9 mod 7 = 2.

N's totatives are strangers to N, meaning they're relatively prime or coprime to N, in addition to being less than N. For two numbers to be relatively prime, their greatest common divisor must be 1, i.e. a,b are coprime (strangers) if gcd(a,b)=1.

Group properties: Closure, Associativity, Inverses, Neutral element or identity (CAIN), with Abelian groups, named for Niels Henrik Abel, being commutative as well.

Whenever multiplication is modulo N over N's totatives, group properties obtain. It's not required that N be a prime. However, if N is prime, and we add 0, the additive identity, to the set (pick another vegetable), and define addition modulo N as well, then we get full-fledged finite field properties, i.e. Z(p) will be a commutative group for both addition and multiplication, plus the distributive law will hold.

Euler's totient function, often symbolized by phi, returns the number of N's totatives. If N is any prime p, then all positives less than p will have no factors in common with p (that's what it means to be prime) and so totient(p) = (p-1) for any prime. Note that we include 1 as a totative. Since 7 is prime, it has six totatives 1-6, which map to bell pepper, chili pepper, carrot, mushroom, beet and celery respectively.

The carrot would be equivalent to the number 3 and, as shown in the demo, has the distinction of being a generator of the group, meaning if you raise it to successive powers, you cycle through all the other vegetables. Do any of the other vegetables do that?

A useful exercise for students would be to create a table of powers, with the veggies down the left, and exponents 0 through 6 across the top. Define any vegetable to the 0th power to be the identity element, i.e. the bell pepper (the bell pepper times any element returns that element unchanged).

Veggie Power!: Veggies to Powers 0-6

When this powers table is complete, you will notice that all vegetables to the sixth power equal the bell pepper (identity element). This result is expected according to Euler's Theorem, which asserts that raising any base b to the power of N's totient, modulo N, returns 1, provided gcd(b,N)=1.

Also note that all rows in the powers table define cyclic subgroups, whether or not they cycle through all members of the original group. Powers of chili peppers times powers of chili peppers give powers of chili peppers -- closure. You'll find inverses and a bell pepper (identity element) in every row of the powers table as well -- necessary conditions for grouphood.

Fermat's Little Theorem is a special case of this, when N is prime, i.e. base b to the (p-1) power mod p = 1, provided gcd(b,p)=1, i.e. b is not a multiple of p.

However, Fermat's Little Theorem (not to be confused with his more famous "last" theorem), does not assert that only primes obey this rule, merely that primes, among others, must obey it.

Indeed, some composite numbers do work in place of p, such that b to the (c-1) mod c = 1. Sometimes this works for some bases and not others (a real prime would work for any relatively prime base), and some work for all bases, these latter being the so-called Carmichael Numbers, named for their discoverer. 561 is the lowest Carmichael number.

For more on totatives and totients in multiplicative groups, see: Jiving in J, Crypto with Python.

~*~*~*~*~*Mike's flippy thing and the imaginary carousel

| anthenya |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Carousel Model from "The Black Mask from Al-Jabr"

Maria Droujkova: The carousel idea comes from a Russian book called "The black mask from Al-Jabr" by Levshin and Alexandrova, first published in 1967. This is one of the books that I dearly wish were translated into English, so I could share it with friends who don't read Russian. Let me translate the relevant pieces for you, and maybe I will put it on the web somewhere for people to find. This is a rough draft, so if you find any grammar errors, please let me know. You are welcome to put it on your web pages, etc... The Russian book is here. Unfortunately, the good people who put it online did not scan the (very cute) pictures of characters working on diagrams. Here is the cover of the 1967 edition:

The book is written as a series of letters to a math club from Tanya, a girl traveling the magical land of Al-Jabr with her friends Oleg and Seva. Here are excerpts from three of several letters related to the carousel metaphor, based on the road metaphor for numbers. I hope they make enough sense without the rest of the context.

The park was full of people. There were numbers and letters walking around. Lately, we've been meeting a lot of letters. Some of them we saw before, but some are total strangers. Mother Two greeted a lot of them and called them by names: "Hello, Mr. Pi! How do you feel today, dear Lady Omega? Oh Epsilon, baby, it's been too long!" We wanted to learn more about all those new letters, but unfortunately, Mother Two stopped to chat with some rather plump Sigma. At this point, we noticed a building with a large "Automatic information station" sign. That's where we can get answers to all our questions! We ascended some stairs and found ourselves in a large well-lit room. It was full of large plastic machines, each with a microphone and a speaker. You approach a microphone, ask your questions and immediately get answers. Al-Jabr has no secrets. Everybody can listen to what the machine says to others. Next to us there was a strange little letter with a tiny red umbrella: i. We heard her sadly asking:

- Please tell me, will I ever find my place in life?

The machine thought for a while, and then replied:

- Even an Imaginary One is good for something.

Little Imaginary One gave a sigh of relief and ran out of the building. Do you understand what is going on? It was bad enough when we had negative ones, and now we get imaginary ones!

On our way we met our old acquaintance - the very same Little Imaginary One who asked the machine earlier if she has a place in life. We immediately recognized her by the little red umbrella.

- Hello, how are you?

- Excellent, - she replied. - The machine told me the truth: even an Imaginary One is good for something.

- You don't say you found a place for yourself on the monorail road?

- Of course, but not on the line where real numbers live. We Imaginary Ones have our own road. It crosses the monorail road exactly at the Zero station.

- How come we never noticed it? - asked Seva.

- Obviously, because our road is imaginary and hard to pay attention to.

- Too bad! - blurted Seva angrily. - Now we have to go back to look at it.

- Sometimes going back to the old stuff is useful, - observed Little Imaginary One. - But you can explore a little piece of the imaginary line right here. There is a new attraction in the park. It's called, "Imaginary Carousel." I work there. Want to see?

As we walked toward the carousel, the advertisements were getting thicker:

WORLD'S FIRST IMAGINARY CAROUSEL! EXCLUSIVELY FOR IMAGINARY ONES! THE ONLY PLACE WHERE IMAGINARY ONES CAN BECOME REAL! JUST FOR YOU, IMAGINARY ONES!

Our handsome friend chattered all the way. She told us many interesting things. It turns out that imaginary one is simply a square root of negative one:

- But why can't you take a square root from minus one? - asked Seva.

- The square root of one is always equal to one, after all.

- Ouch! - exclaimed the horrified Little Imaginary One. - This only work for the positive one. For example, what does it mean to take the square root of, say, nine?

- It means to find such a number that will give you nine when you square it, - replied Oleg.

- This number is three.

- Right. Now try to find a number that gives you minus one when you square it!

Little Imaginary One laughed in her high-pitched voice. Seva ruffled his hair, puzzled.

- Mmmm... There is no such number! Whatever number you square, positive or negative, the answer's always positive. This I know for sure!

- You see! That's why the square root of minus one is called "imaginary one."

- This means imaginary ones are very special numbers. I guess your monorail line works in some special way, too.

- Not at all. Our line looks is very similar to the line where real numbers live, but perpendicular to it. It's the same sort of an infinite line with the center at the same Zero station.

- If you have the Zero station, then you must have positive and negative numbers?

- How could you! Imaginary numbers can never be positive or negative! Our road simply has two directions from zero, just like the road of real numbers. One of them is denoted by the plus sign and the other by the minus sign.

- But how can you tell imaginary numbers from real numbers?

- With some help from the letter i: 2i, 5i, - 8i, - 12i.

- Is that so? But then you must have coefficients, just like all the other letters of Al-Jabr?

- Of course. - And where is your coefficient? - blurted out Seva.

When will he ever learn any manners? Good thing well-bred Little Imaginary One pretended she did not notice his rudeness.

- My coefficient is one, and it's invisible, as usual.

But Seva was plowing right ahead. He can argue you to death.

- Here you are saying that the imaginary monorail road is like the real monorail road. But that means it has the same traffic rules. Right? Then what does it have to do with carousels? After all, the real monorail road is a straight line, and carousels go around!

- You are partially right, - replied Little Imaginary One. - Our traffic rules have more variety. When we add or subtract, our cars move in the straight line, by the same rules as real numbers:

2i + 3i = 5i

8i - 15i = - 7i

Or like this:

- 3i + 9i = 6i

And, of course:

5i - 5i=0.

Imaginary Ones with opposite signs and the same coefficients destroy each other at the Zero station. But multiplication, division, or powers - that's another story! Here Imaginary Ones move not only in straight lines. You'll see in a minute.

We entered a round building. It was full of Imaginary Ones. All of them were impatiently waiting their turn on the carousel.

- The seats here are in an amphitheater around the arena in the middle. It is intersected by two bars. One bar represents the monorail road of the real numbers. It has the +1 and the -1 signs on its ends. The other bar represents the road of the imaginary numbers. Here, you see the +i and -i signs. At the intersection of the roads in the middle of the arena is the Zero station. It has a rotating axis with a transparent plastic circle on it, like a record on a turntable. When we entered, the carousel stopped. An Imaginary One with a green umbrella lightly jumped off it. Taking her place, exactly next to the +i sign, an Imaginary One with a yellow umbrella entered. Our guide took a microphone and commanded:

- Get ready to be taken to powers!

A bell rang, and the circle started to move to the sounds of a rolling waltz. Except it wasn't moving clockwise, but in the opposite direction. And then wondrous things started to happen! Imaginary One with a yellow umbrella crossed the road of real numbers next to the -1 sign and turned into a real number, Negative One. At the next sign, she became Imaginary One again, but now with the minus sign. Then she crossed the real road again, and as she was next to the +1 sign, she miraculously transformed from Imaginary One to Real One again, with a plus sign yet! And then she approached the i sign and turned back into Imaginary One. The orchestra started to play the song, "You are what you are!" and everything repeated once more. The carousel was going around and around, and Imaginary One was transforming again and again.

- I don't get it, - said Seva. - Imaginary One turns into Real One, and Real One turns back into Imaginary One... How does it happen?!

- That's how powers work! - replied Little Imaginary One. - After all, Imaginary One is equal to the square root of minus one:

But if you square a square root of any number, what do you get?

- Whatever number was under the square root, - replied Oleg. - Oh, we saw it recently. One local guy kept squaring either square root of three, or square root of two for an hour... And every time he got whatever number was under the square root sign.

- The same happens to Imaginary One:

- This I understand. But how does a real number, minus one, transform into an imaginary number?

- This happens when Imaginary One is not squared, but cubed, that is, taken to the third power:

This is the same as multiplying -1 by i:

- 1 * i = - i.

- Now, - said Oleg, - it's easy to understand how Imaginary One with the minus, -i, turns into Real One with the plus, +1. It is taken to the fourth power:

You can also imagine it like this:

- 1 * - 1 = + 1

- Wonderful! - Little Imaginary One exclaimed. - The only thing left to do is to figure out how Real One becomes imaginary.

Indeed, how? Even Oleg had no idea. But it turned out you need to raise Imaginary One to the fifth power.

- It's impossible!

- What does it mean?

- Nothing special:

To get

1*i=i

- What a puzzle! Imaginary One does not work with powers over four? - wondered Oleg.

- Why not! - said Little Imaginary One. - You can raise it to sixth, seventh, or one hundred twenty first power... Any whole power. You just won't get anything new. That's why it's a carousel.

At this point, Seva demanded to know what is i to the seventeenth power.

- It's really easy. i to the fifth power is i, - said Little Imaginary One. - It means that i to the ninth power is also i...

- I get it! - interrupted Seva. - You just add four to the power: thirteenth power is equal to i, and then seventeenth power is also equal to i.

Here is a good problem. Try to figure out what's i to the twenty-fourth power. To make it easier, look at the picture of the carousel.

This picture is from an English web page from BetterExplained:

Marta Calvo's Story: Rotation Groups with Miran (7)

We started by making out own rotating around a point triangle (a triangle of one color attached with a tack and secured with a piece of eraser to sheet of paper of contrasting color) marking its original position and naming all 3 rotations. Then, after a couple of initial questions (about the angles of rotation which Miran happily computed; commutation, invers) we filled out the first part of the multiplication table. Next, we cut out another triangle and attached different colored straws to mark the axes for flips. Miran refused to describe them, as he considered color coding sufficient.

Then, before we started filling out the multiplication table, I asked him to predict if the product is going to be rotation around the point or a flip. At that point he started looking for patterns in the table and we filled the rest of the table very quickly. Afterward, he initiated a game of finding out the product of three rotations and tried to give me tricky ones (we were taking turns). And, only after Miran did it hands-on with his paper triangles, I showed him 'the flippy thing' program, and the main part of playing was figuring out how it works, looking for patterns, and comparing with what we did ourselves.

That week we proceeded with the rotation group of the rectangle (which Miran said was too easy) and the square which was initially too overwhelming due to the number of rotation axes. Miran did the square in two steps, first the rotations around the point and the next day the rotations around the axes. Again, what helped was looking for patterns in the multiplication table and a guessing game (predict first, check later).

During that week we kept talking about the Abelian groups and the four conditions that such a group has to meet. Miran was fine with that more abstract part as long as I was giving solid examples, showing connections between what he knows and new ideas, and playing games that allowed him to be a partner in this activity and challenge his mom, too.

~*~*~*~*~*Raymond's "polar" model and Madison's cartoon about it

The complex answer

by Raymond FaberThis might seem too abstract for some:

On the left panel, I show the numbers in different colors. Zero is in the middle.

From the middle, moving to the right (Yellow) are the positive real numbers.

From the middle, moving to the left (Blue) are the negative real numbers.

From the middle, moving up(Red) are the positive multiples of i, the square root of -1. And down(Green) are the negative multiples of i.

The two panels on the right, show where each number ends up after you square it. As you can see, the negative Blues end up on the positive side (right) after you square them.

I could explain why exactly the right side has two panel instead of one... but I'll leave it at this.

An explanation of angle correspondences by Madison Cross Sugg. Color-coding (reg goes to red and so on) is separate from the above pictures.

Cheers,

Maria Droujkova

Make math your own, to make your own math.