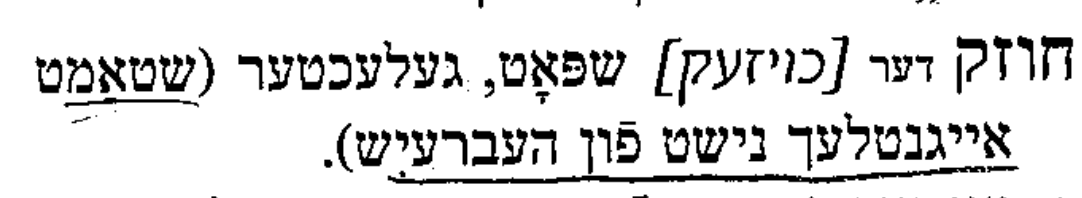

Making Chozek

RCK

Zei Gezunt & Kol Tuv,

Reuven Chaim Klein

Beitar Illit, Israel

Author of: God versus Gods: Judaism in the Age of Idolatry & Lashon HaKodesh: History, Holiness, & Hebrew

ORCiD | LinkedIN | Google Scholar | Amazon

From: RC Klein <yesh...@gmail.com>

Date: Wed, Sep 9, 2020 at 8:34 PM

Subject: The Strong Ones

To: <whats-i...@googlegroups.com>

As Moses passed the torch of leadership to his protégé and successor Joshua, he said to the younger padawan, Chazak V’Ematz — “Be strong and be strong” (Deut. 31:7, 31:23). After Moses’ passing, G-d Himself reiterated that messaging, using this expression four more times when speaking to Joshua (Josh. 1:6–18). Generations later, when King David gave a pep talk to his son and future successor Solomon, he too said, Chazak V’Ematz (I Chron. 22:13, 28:20). What is the deeper meaning of this seemingly redundant expression that uses two words for “strength” — chozek (chizzuk) and ometz (imutz)? What other words in Hebrew mean “strength” or “power,” and how do they differ from the words that opened our discussion?

Rabbi Avraham Bedersi HaPenini (a 13th century Spanish sage) and Rabbi Shlomo Aharon Wertheimer (1866–1935) explain that ometz refers to an above-normal amount of “strength,” while chozek remains the standard term for “strength.” For example, if a person grew especially weak, but was then nursed back to health and was now “strengethened” to be as strong as a normal person, the word chozek is appropriate. In such a case, the term ometz cannot be applied, because the “strength” in question is not more than that which a regular person possess.

The Vilna Gaon (to Josh. 1:7, Prov. 24:5) explains that chozek refers to outer “physical strength,” while ometz denotes strength “in the heart.” This explanation is echoed by the Malbim in his work Yair Ohr on synonyms in the Hebrew language; but, elsewhere, the Malbim (to Isa. 28:2) seems to take a different approach. There, he explains that chozek refers to a sort of temporary strength. With time, such strength tends to atrophy, slowly, but surely, losing its potency. On the other hand, ometz refers to a more resilient form of strength that constantly recharges itself and never weakens or falters.

In his work HaRechasim LeVikah (Gen. 25:23), Rabbi Yehuda Leib Shapira-Frankfurter (1743–1826) departs from this model and speaks about three types of “strength.” In his assessment, gevurah refers to “physical strength,” ometz refers to the “strength in one’ heart” (i.e. one's spiritual resolve), and chozek refers to the “strength of will” (i.e. courage). To illustrate the difference between the latter two, he explains that chozek is necessary to enter a battle or any dangerous situation without being scared, while ometz is the courage to remain in battle and not run away when things heat up.

The Talmud (Brachos 32b) explains that when G-d told Joshua Chazak V’Ematz, He meant to encourage Joshua in two specific areas. With the word chazak, He intended to motivate Joshua to strengthen himself in Torah Study, while with the word ematz, He meant to encourage Joshua in the performance of good deeds. How does this fit with what we have learned? Rabbi Wertheimer explains that the greater a Torah Scholar one becomes, the more effort he must exert into being able to perform good deeds. Such a person must harness super-human efforts to fortify his will to make sure he continues performing good deeds and does not simply lose himself in the more theoretical world of study. In light of the above, the strength of will required to do this is most appropriately termed ometz.

Rabbi Shlomo Pappenheim of Breslau (1740–1814) traces the word ometz to the two-letter root MEM-TZADI, which means “sucking” or “squeezing.” Other derivatives of this root include mitz (“juice”) and metzitzah (“sucking”). Ometz relates back to this root’s core meaning because it refers to a person mustering all his strength and “squeezing” out every last ounce of energy. Red horses are described as amutzim (Zech. 6:3) because they exert so much effort that their blood rises to the surface of their skin as if it was “squeezed out,” and this causes even their hairs to be colored red.

Rabbi Dr. Asher Weiser (editor of the Mossad HaRav Kook edition of Ibn Ezra’s commentary to the Pentateuch) argues that the word ometz is related to the similar word otzem (“strength”). He establishes this connection by noting that the ALEPH of ometz is interchangeable with the AYIN of otzem, and the other two consonants switch places by way of metathesis.

How does otzem mean “strength”? Rabbi Yehuda Leib Edel (1760–1828) explains that otzem/etzem refers to growth in the sense of added quantity (see Ex. 1:8, 1:20, Deut. 7:1, Joel 2:2, Ps. 35:18). In other words, otzem refers to “strength through numbers.” From that import, the word expanded to refer also to “inherent strength,” i.e. added quality, not just quantity. Alternatively, he explains that otzem in the sense of “strength” is borrowed from the word etzem (“bone”) because the bone is physically the strongest component of one’s anatomy.

Rabbi Moshe Shapiro (1935–2017) notices a common theme among all words that contain the two-letter string AYIN-TZADI. The word eitz denotes a “tree,” which contains within itself everything that will be created from it. In fact, this relates to the self-referential word etzem (“self”), which contains the sum total of all of one’s potential. We encounter this idea again in the word atzuv (“sad”), which describes a person who retreats into himself and fails to expand outwards; the same is true of the atzel/atzlan (“lazy” or “indolent” person) who keeps all his potential bottled up inside of him and does not bother to act on it. Otzer (“stop”) similarly refers to holding something back from further expanding, thus keeping its potential for growth locked up inside. The Hebrew word for “advice” (eitzah/yoetz) similarly uses this two-letter combination because an honest advisor can only offer his counsel to the extent that he grasps the entirety of the situation—the etzem of what is being considered. In line with this, Rabbi Shapiro explains that otzem refers to one’s potential strength that is pent-up within him but has not yet been outwardly expressed. [Rabbi Pappenheim offers a similar exposition on the biliteral root AYIN-TZADI.]

Rabbi Aharon Marcus (1843–1916) writes that a tree is called eitz because of its “hard” or “strong” trunk. He further writes that atzuv is related to eitz in the sense of “wood,” because it is a “dry” emotional state in which one is bereft of life and happiness. In a fascinating twist, Rabbi Marcus connects the words otzem and eitz to oz — all of which mean “strong/hard”— by noting the interchangeability of TZADI and ZAYIN.

Rabbi Wertheimer compares the word oz/izuz in the sense of “strong” to the word az, which also means “strong” or “bold.” He explains that the AYIN-ZAYIN combination refers to the strength of one’s spirit/resolve in that he cannot be easily dissuaded or deterred by others. A person's oz is so palpable that it can be physically reflected in his face (see Ecc. 8:1), and it is therefore poetically called a “garment” in which a person dresses (see Prov. 31:24).

When Moses sent spies to scout out the Holy Land before the Jews’ attempt at conquest, he asked them to examine whether the Canaanites were “strong (chazak) or weak” (Num. 13:18). But, when the spies returned, they said that the Canaanites were “strong” (Num. 13:28) using a different word—az. Rabbi Wertheimer accounts for this word-switch by explaining that the spies were originally charged with determining whether or not the Canaanites were physically strong (chazak). Instead of doing this, they decided to examine the Canaanites’ psychological resolve, concluding that they were so strong-willed and motivated to fight, that their determination could be seen on their faces (az/oz).

Interestingly, Rabbi Naftali Hertz (Wessely) Weisel (1725–1805) writes that the primary meaning of oz always refers to Divine supernatural powers/abilities (in contrast to gevurah, which can also refer to powers/abilities within the normal course of nature). Rabbi Yehuda Edel cites Weisel, and adds that this is what it means when it says, “G-d gives oz to His nation” (Ps. 28:11). In other words, He elevates the Jewish People above the rules of nature to the realm of the supernatural. According to this, it only in a borrowed sense that oz can refer to anything that is “strong” or “powerful.”

When the Psalmist exhorts the reader to “Give oz to G-d” (Ps. 68:35), this does not literally mean that a mere mortal can actually strengthen G-d. Rather, it means that when the Jewish People follow G-d’s will, then He showers them with more abundance, as if they had given Him more energy (see Eichah Rabbah §1:33). Rabbi Yerucham Levovitz (1873–1936) offers a powerful insight related to this idea. Obviously, we cannot actually power G-d; yet, He gives us the opportunity to feel like we are doing so in order to teach us a lesson. When you do a favor for somebody, then you should allow him to do something else for you in return, just so that the beneficiary of your favor does not feel forever indebted to you for doing him that favor. In the same way, when G-d does us the ultimate favor of giving life and sustaining us, He also gives us a chance to feel like we can do something for Him in return by following the Torah and giving Him oz.

The word takif is the standard Aramaic translation for chozek and oz in the Targumim. It is also a Hebrew word that appears in the Bible (see Est. 9:29, 10:2, Ecc. 4:12, Dan. 4:27). Rabbi Pappenheim traces the word takif to the two-letter root KUF-PEH, which means “complete circle.” Other words derived from this root include hakafah/haikef (“circumference,” “encircle”) and kafah/kafui (“frozen,” because first the outer perimeter that surrounds the liquid freezes first, and only afterwards does the rest of it freeze over). Interestingly, Rabbi Pappenheim relates the word kof (“monkey”) to this two-letter root, but admits that he does not know how to explain the connection.

Rabbi Pappenheim further explains that chozek refers to strength in one’s ability to withstand being overpowered by another, while tokef refers to strength in the sense of one’s ability to actually overpower others.

Rabbi Pappenheim’s etymology of the word takif is reminiscent of his explanation of the word chayil (“strength”), which he similarly traces to the two-letter root CHET-LAMMED (“circular motion”). Accordingly, tokef/takif refers to a level of strength/potency whereby one can totally surround and overpower another.

Rabbi Edel explains that when we describe God as takif, this invokes His all-encompassing (i.e. all-around) power/sovereignty. The Aramaic expression matkif commonly found in the Talmud refers to one sage “attacking” or “overpowering” another sage’s position with a persuasive argument.

Rabbi Shlomo of Urbino (a late 15th century Italian scholar) writes in Ohel Moed (his lexicon of synonyms) that there are 36 words in Biblical Hebrew for “strength” or “power”! Although Yonah Wilheimer (1830–1913) — the Viennese publisher of the 1881 edition of Ohel Moed — notes that this is somewhat of an exaggeration, it remains true that we have only scratched the surface of this topic…

To be continued…

Kesivah V'Chasimah Tov!

May all of Kllal Yisroel have a Good and Blessed Year!

Reuven Chaim Klein

Beitar Illit, Israel

Author of: God versus Gods: Judaism in the Age of Idolatry & Lashon HaKodesh: History, Holiness, & Hebrew ORCiD | LinkedIN | Google Scholar | Amazon

Binah T. Gordon

- To begin with, the kumets vowels historically shift to /o/ (or /u/ in my variety).

- There is also the stress shift, followed by reduction of unstressed vowels.

- The spelling with <e> is simply a common way of transliterating unstressed vowels. (I prefer to symbolize the underlying value and add a breve accent for clarity.) It is underlyingly still kumets.

Sarah Benor

--

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "Jewish Languages" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to jewish-languag...@googlegroups.com.

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/jewish-languages/e4896ddc-f35c-4416-b0c4-6af45d9a1bdan%40googlegroups.com.

Alexandre Beider

[1] Weinreich (WG 3:322) points to the 19th century reference, but considers the earliest reference to be present in a dictionary of “German-Jewish” language (actually describing SWY) where it appears as cheisik and is translated to German as “Belustigung” ‘amusement’ (PhilogLottus 1733:15). Note that (1) the root does not use the diphthong /ou/ (that in the Yiddish dialect in question corresponds to StY oy), but either /aj/, or /ej/; (2) the meaning in StY is different. As a result, this reference can be unrelated to StY khoyzek, but represent a variant (possibly, errroneous) of StY kheyshek ‘desire’ (from Hebrew חֵשֶׁק), that appears in the same book as cheischik “Lust” ‘desire’ (PhilogLottus 1733:36).

Alexandre Beider

Isaac L. Bleaman

Isaac L. Bleaman

Assistant Professor, Department of Linguistics

University of California, Berkeley

https://www.isaacbleaman.com

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/jewish-languages/CAOpx48uBz0cAaZuUCBDs_n3QBgm6%2BpSt8g3oztV3hpGHqNTwTQ%40mail.gmail.com.

Isaac L. Bleaman

Assistant Professor, Department of Linguistics

University of California, Berkeley

https://www.isaacbleaman.com

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/jewish-languages/1708648251.5399832.1599754620689%40mail.yahoo.com.