Musings on Markets

0 views

Skip to first unread message

Rishi Chourasia

Oct 22, 2015, 8:17:55 AM10/22/15

to

Musings on Markets |

|

Dream Big or Stay Focused? Lyft's Counter to Uber! Posted: 19 Oct 2015 04:04 PM PDT This is the second in a series of three posts on the ride sharing business. In my first, published in both TechCrunch and my blog, I valued Uber, trying to incorporate the news that has come out about the company and its competition in the last year. In this one, I first turn to valuing Lyft, which is telling a narrower, more focused story to investors than Uber and also look at how the pricing ladder in ride sharing companies has pushed up prices across the board. In the last post, due out on Wednesday, I will look at the ride sharing market as a business. In my last post, I valued Uber and admitted that the company has made its way to my list of obsessions. My focus on Uber, though, has meant that I have not paid any attention to the other ride sharing company in the US, Lyft, and I don’t think I have been alone in this process. An unscientific analysis of news stories on ride-sharing companies in the last couple of years suggests that Uber has dominated the coverage of this business. Rather than view this as a slight on Lyft, I would argue that this is at least partially by design, and that it is part of both companies' strategies. Uber is viewed as the hands-down winner of this battle right now, but this is just one battle in a long war and investors define winners differently from corporate strategists. Valuing Lyft To value Lyft, I will employ the same template that I used for Uber, though the choices I will make in terms of total market, market share, operating margins and risk will all be different, reflecting both Lyft’s smaller scale and more limited ambitions (for the moment). The Leaked NumbersThe place to start this assessment is by comparing the ride sharing reach of Lyft with Uber and that comparison is in the table below:

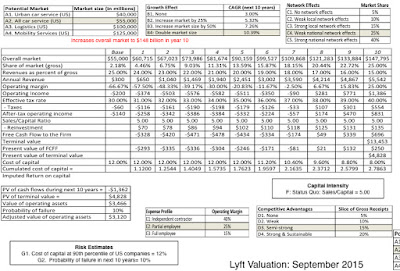

The key differences can be summarized as follows. First, Uber is clearly going after the global market, uninterested in forming alliances or partnerships with local ride sharing companies. Lyft has made explicit its intention to operate in the US, at least for the moment, and that seems to have been precursor to forming alliances (as evidenced by this news story from two weeks ago) with large ride sharing companies in other markets. Within the US, Uber operates in more than twice as many cities as Lyft does. Second, both companies are growing, though Uber is growing at a faster rate than Lyft, and that is captured in both the number of rides and gross billings at the companies. Third, both companies are losing money and significant amounts at that, as they go for higher revenues. Note that, for both companies, the bulk of the information comes from leaked documents, and should therefore considered with skepticism. In addition, there are some numbers that come from press reports (Lyft's loss in 2014) that are more guesses than estimates. The business models of the two companies, at least when it comes to ride sharing, are very similar. Neither owns the cars that are driven under their names and both claim that the drivers are independent contractors. Both companies use the 80:20 split for ride receipts, with 80% staying with the driver and 20% going to the company, but that surface agreement hides the cut throat competition under the surface for both drivers and riders. Both companies offer incentives (think of them as sign-up bonuses) for drivers to start driving for them or, better still, to switch from the other company. They also offer riders discounts, free rides or other incentives to try them or, better still, to switch from the other ride sharing company. At times, both companies have been accused of stepping over the line in trying to get ahead in this game, and Uber’s higher profile and reputation for ruthlessness has made it the more commonly named culprit. The other big operating difference is that unlike Uber, which is attempting to expand its sharing model into the delivery and moving markets, Lyft, at least for the moment, has stayed much more focused on the ride sharing business, and within that business, it has also been less ambitious in expanding its offerings to new cities and new types of car services than Uber. The Narrative Contrast and Valuation In my valuation of Lyft, I will try to incorporate the differences that I see (from Uber) into my narrative:

In short, the Lyft narrative is narrower and more focused (on ride sharing and in the US) than the Uber narrative. That puts them at a disadvantage, at least at this stage in the ride sharing market, in terms of both value and pricing, but it could work in their favor as the game unfolds. The adjustments to the Lyft valuation, relative to my Uber valuation, are primarily in the total market numbers, but I do make minor adjustments to the other inputs as well.

The value that I get for Lyft is $3.1 billion, less than one seventh of the value that I estimated for Uber ($23.4 billion) in my last post. The biggest danger that I see for investors in Lyft is that the company has to survive the near future, where the pressure from Uber and the nature of the ride sharing business will create hundreds of millions of dollars more in losses. If the capital market, which has been accommodating so far, dries up, Lyft faces the real danger of not making it to ride sharing nirvana. It is a concern amplified by Mark Shurtleff at Green Wheels Mobility Solutions, a long-time expert and consultant in the ride sharing and mobility business, who points to Lyft's concentration in a few cities and cash burn as potential danger signs. Pricing The Ride Sharing Companies While none of the ride sharing companies are publicly traded and there are therefore no prices (yet) for me to compare these valuations to, there have been investments in these companies that can be extrapolated at some risk to estimate what these investors are pricing these companies at. In keeping with my theme that price and value come from different processes, recognize that these are prices, not values. The VC Pricing I took at look the most recent VC investments in ride sharing companies and what prices they translate into.

* Sources: Public News Reports, Mark Shurtleff The danger in extrapolating VC investments to overall value, which is what the press stories that report the overall prices do, is that the only time that a VC investment can be scaled up directly to overall value is if it comes with no strings attached. Adding protections (ratchets) or sweeteners can very quickly alter the relationship, as I noted in this post on unicorns. Notwithstanding that concern, is there a logic to this pricing? In other words, what makes Uber more than three times more valuable than Didi Kuaidi and Didi Kuaidi six times more valuable than Lyft? To answer these questions, I pulled up the statistics that I could find for each of these companies:

* The revenues are estimated using the revenue slice that these companies report, but with customer give aways and other marketing costs, the actual revenues were probably lower. Note that almost all of these numbers come from leaks, guesses or judgment calls, and that there are many items where the data is just not available. For instance, while we know that Ola, GrabTaxi and BlaBlaCar are all losing money, we do not know how much. At the risk of pushing my data to breaking point, I computed every possible pricing multiple that I could for these companies:

On a pure pricing basis, Lyft looks cheap on every pricing multiple, and Uber looks expensive on each one, perhaps providing some perspective on why Carl Icahn found Lyft to be a bargain, relative to Uber. Didi Kuaidi looks expensive on any measure other than gross billing and GrabTaxi looks cheap on some measures and expensive on others. It is worth noting that these companies have different revenue models, with Lyft and Uber hewing to the 20% slice model, established in the US and Ola (which has more of a taxi aggregating model), at least according to the reports I read, follows the same policy. BlaBla is mostly long-distance rides and gets about 10-12% of the gross billing as revenue, GrabTaxi gets only 5-10% of gross billings, Didi Kuaidi, which had its origins in a taxi hailing app, gets no share of a big chunk of its revenues and BlaBlaCar derives its revenues more from long distance city-to-city traffic than from within city car service. Given how small the sample is and how few transactions have actually occurred, I will not attempt to over analyze these numbers, other than wondering, based on my post on corporate names, how much more an umlaut would have added to Über's hefty price. Big versus Small Narratives With all of these companies, the prices paid have risen dramatically in the last year and a half and I believe that this pricing ladder is driven by Uber's success at raising capital. In fact, as Uber's estimated price has risen from $10 billion early in 2014 to $17 billion last June to $40 billion at the start of 2015 to $51 billion this summer, it has ratcheted up the values for all of the other companies in this space. That should not be surprising, since the pricing game almost always is played out this way, with investors watching each other rather than the numbers. As with all pricing games, the danger is that a drop in Uber's pricing will ratchet down the ladder, causing a mark down in everyone's prices. If narrative drives numbers and value, which is the argument that I have made in valuing Uber and Lyft in these last two posts, the contrast between the two is also in their narratives. Uber is a big narrative company, presenting itself as a sharing company that can succeed in different markets and across countries. Giving credit where it is due, Travis Kalanick, Uber’s CEO, has been disciplined in staying true to this narrative, and acting consistently. Lyft, on the other hand, seems to have consciously chosen a smaller, more focused narrative, staying with the story that it is a car service company and further narrowing its react, by restricting itself the US. The advantage of a big narrative is that, if you can convince investors that it is feasible and reachable, it will deliver a higher value for the company, as is evidenced by the $23.4 billion value that I estimated for Uber. It is even more important in the pricing game, especially when investors have very few concrete metrics to attach to the price. Thus, it is the two biggest market companies, Uber and Didi Kuaidi, which command the highest prices. Big narratives do come with costs, and it those costs that may dissuade companies from going for them.

With Uber, you see the pluses and minuses of a big narrative. It is possible that Uber Eats (Uber’s food delivery service), UberCargo (moving) and UberRush (delivery) are all investments that Uber had to make now, to keep its narrative going, but it is also possible that these are distractions at a moment when the ride sharing market, which remains Uber’s heart and soul, is heating up. It is undoubtedly true that Uber, while growing at exponential rates, is also spending money at those same rates to keep its big growth going and it is not only likely, but a certainty, that Uber will disappoint their investors at some time, simply because expectations have been set so high. It is perhaps to avoid these risks that Lyft has consciously pushed a smaller narrative to investors, focused on one business (ride sharing) and one market (the US). It is avoiding the distractions, the costs and the disappointments of the big narrative companies, but at a cost. Not only will it cede the limelight and excitement to Uber, but that may lead it to be both valued and priced less than Uber. Uber has used its large value and access to capital as a bludgeon to go after Lyft, in its strongest markets. As an investor, there is nothing inherently good or bad about either big or small narratives, and a company cannot become a good investment just because of its narrative choice. Thus, Uber, as a big narrative company, commands a higher valuation ($23.4 billion) but it is priced even more highly ($51 billion). Lyft, as a small narrative company, has a much lower value ($3.1 billion) but is priced at a lower number ($2.5 billion). At these prices, as I see it, Lyft is a better investment than Uber. Block and Draft It is clear that Uber and Lyft have very different corporate personas and visions for the future and that some of the difference is for outside consumption. It serves Uber well, in its disruptive role, to be viewed as a bit of a bully who will not walk away from a fight, just as it is Lyft’s best interests to portray itself as the gentler, more humane face of ride sharing. Some of the difference, though, is management culture, with Uber drawing from a very different pool of decision-makers than Lyft does. If this were a bicycle race, Uber reminds me of the aggressive lead rider, intent on blocking the rest of the pack and getting to the finish line first, and Lyft is the lower profile racer who rides just behind the leader, using the draft to save energy for the final push. This is going to be a long race, and I have a feeling that its contours will change as the finish line approaches, but whatever happens, it is going to be fun to watch! YouTube Version Ride Sharing Series (September 2015)

|

Thanks & Regards,

Rishi Chourasia

(Founder Director)

Vikalp Education

Refine Your Talent

Nagpur | Pune | Mumbai

Website: http://onlinevikalp.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/vikalpeducation

Twitter :https://twitter.com/MgmtVikalp

Rishi Chourasia

Oct 26, 2015, 7:23:00 AM10/26/15

to

Musings on Markets |

|

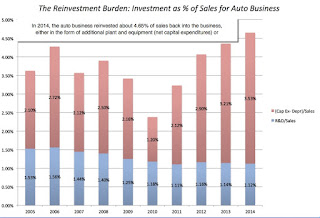

The Ferrari IPO: A Price Premium for the Prancing Horse? Posted: 15 Oct 2015 05:41 PM PDT I live in a prosperous suburb, sustained largely by financial service businesses, but as far I know, there is only one Ferrari in my town. Much of the week, the car sits in a garage which has its own security system, more secure than the one protecting its owner's house, and on a nice weekend, you see the owner drive it around town. It is a remarkably inefficient transportation mode, too fast for suburban roads, too expensive to be parked at a grocery story or pharmacy, and too cramped for car pool. All of this comes to mind, for two reasons. The first is the imminent initial public offering of the company, with all the pomp and circumstance that surrounds a high-profile offering. The second is that this offering has set in motion the usual talk of brand names and the price premiums that we should pay to partake for investing in them. Ferrari: A Short History and Background The Ferrari story started with Enzo Ferrari, a racing car enthusiast, starting Scuderia Ferrari in 1929, to assist and sponsor race car drivers driving Alfa Romeos. While Enzo manufactured his first racing car (Tipo 815) in 1940, Ferrari as a car making company was founded in 1947, with its manufacturing facilities in Maranello in Italy. For much of its early existence, it was privately owned by the Ferrari family, though it is said that Enzo viewed it primarily as a racing car company that happened to sell cars to the public. In the mid-1960s, in financial trouble, Enzo Ferrari sold a 50% stake in the company to Fiat. That holding was subsequently increased to 90% in 1988 (with the Ferrari family retaining the remaining 10%). Since then, the company has been a small, albeit a very profitable, piece of Fiat (and FCA). The company acquired its legendary status on the race tracks, and holds the record for most wins (221) in Formula 1 races in history. Reflecting this history, Ferrari still generates revenues from Formula 1 racing, with its share amounting to $67 million in 2014. Much as this may pain car enthusiasts everywhere, some of Ferrari's standing comes from its connection to celebrities. From Thor Batista to Justin Bieber to Kylie Jenner, the Ferrari has been an instrument of misbehavior for wealthy celebrities all over the world. The Auto Business In earlier posts, where I valued Tesla, GM and Volkswagen, I argued that the auto business bore the characteristics of a bad business, where companies collectively earn less than their cost of capital and most companies destroy value. In fact, I used the words of Sergio Marchionne, CEO of Fiat Chrysler (and the parent company to Ferrari) to make the case that the top managers at auto companies were delusional in their belief that the business would magically turn around. Looking at the business broadly, here are three characteristics that reveal themselves: 1. It is a low growth business: The auto business is a cyclical one, with ups and downs that reflect economic cycles, but even allowing for this cyclicality, the business is a mature one. That is reflected in the growth rate in revenues at auto companies.

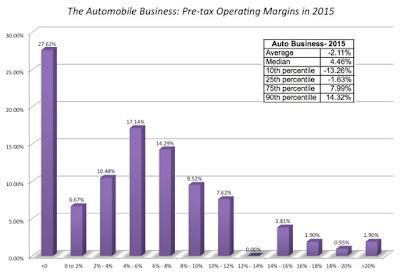

2. With poor profit margins: A key point that Mr. Marchionne made about the auto business is that operating margins of companies in this business were much too slim, given their cost structures. To illustrate this point (and to set up my valuation of Ferrari), I computed the pre-tax operating margins of all auto companies globally, with market capitalizations exceeding $1 billion, and the graph below summarizes my findings.

It is this combination of anemic revenue growth, slim margins and increasing reinvestment that is squeezing the value out of the auto business. (You can download the data for all auto companies, with profitability measures and pricing ratios by clicking here.) The Super Luxury Automobile Business If, as has been said before, the only difference between the rich and the rest of us is that the rich have more money, the difference between the rich and the super rich is that super rich have so much money that they have stopped counting. The super luxury car manufacturers (Ferrari, Aston Martin, Lamborghini, Bugatti etc.), with prices in the nose bleed segment, cater to the super rich, and have seen sales grow faster than the rest of the auto industry. Much of the additional growth coming from newly minted rich people in emerging markets, in general, and China, in particular. Like the rest of the companies in the super luxury segment, Ferrari is less auto company and more status symbol, and draws its allure from four key characteristics:

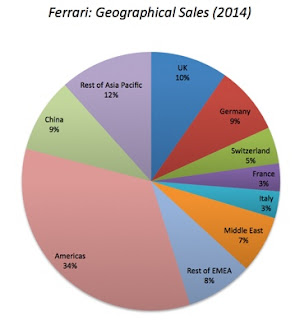

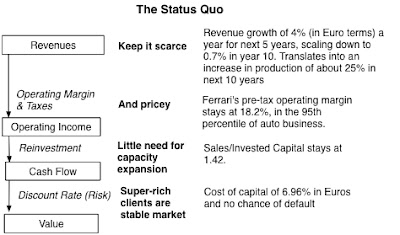

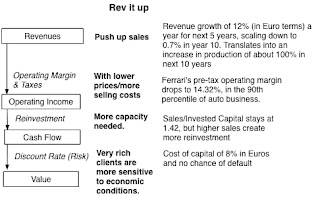

To illustrate how exclusive the Ferrari club is, in all of 2014, the company sold only 7255 cars, a number that has barely budged over the last five years. (The Lamborghini club is even more exclusive, with only 2000 cars sold annually.) The company has its roots in Italy but is dependent on a super- rich clientele globally for its sales: Note that a significant slice of the revenue pie comes the Middle East and that Ferrari, like many other global companies, is becoming increasingly dependent on China for growth. Valuing Ferrari As many of you reading this blog are aware, I am a believer that all valuations start with stories and that different stories can yield different valuations. With Ferrari, there are two plausible stories that you can offer for the future of the company, with valuations to back them up: 1.The Status Quo (Super Exclusive, Low Production, High Margin) The story: Ferrari remains a extra-exclusive automobile company, keeping production low and prices high. The benefits of this strategy are high operating margins (Ferrari has among the highest in the auto business) partly because of the high prices, and partly because the company does not have to spend much on expensive ad campaigns or selling. It also will keep reinvestment needs to a minimum, since capacity expansion will not be necessary, though the company will continue spending on R&D to preserve its edge (on speed and styling). In addition, by focusing on a very small group of super rich people around the world, Ferrari may be less affected by macroeconomic forces than other luxury auto companies. The inputs: The inputs into my valuation reflect the story, with low revenue growth, high margins and low reinvestment driving value: The valuation: With these assumptions, the value for equity of 6,310 million Euros (approximately $7 billion). You can download the spreadsheet here. 2. Rev it Up (Increase production, Introduce a lower-priced model) The story: Ferrari tries to broaden its customer base, perhaps by introducing a lower-priced version; this would mirror what Maserati did with its Ghibli model. That will allow for higher revenue growth but like Maserati, Ferrari will have to yield some of its operating margin, since this strategy will require lower prices and higher selling costs. Seeking a larger market will also expose it to more market risk, pushing its cost of capital in high growth to 8.5% and its cost of capital beyond to 7.5%. The inputs: This strategy will generate higher sales (doubling number of units sold in next ten years) but at the expense of lower margins (from lower prices and higher selling costs) and higher risk (as the clientele will be more sensitive to economic conditions). The valuation: With this strategy, the value for equity of 6,042 million Euros (approximately $6.75 billion). You can download the spreadsheet here. At least based on my estimates, it is more sensible for Ferrari to stick with its low-growth, high price strategy and keep itself above the fray of the auto business, a bad business where most companies seem to have a tough time earning their cost of capital. The Brand Name Premium There is a lot of casual talk about how Ferrari will command a premium because of its name and some have suggested that you should add that premium on to estimated value. In an intrinsic valuation, it is double counting to add a premium and the reason is simple. The values that I have estimated already incorporate the premium. If you are wondering how, take a look at the operating margin of 18.20% that I have used for Ferrari, a number vastly in excess of the margins earned by other auto companies. That high margin, in conjunction with limited growth in cars sold, also allows Ferrari to earn a return on capital of 14.56%, well above its cost of capital. These inputs yield a value premium, with the magnitude varying across multiples:

Thus, the intrinsic value estimates already are building in a hefty premium for the effects that Ferrari's brand name has on its operating margins and return on capital. Is it possible that the brand name can be utilized better? That is always possible but there is nothing to indicate that the brand is being mismanaged or that it can be easily exploited to generate additional value. In fact, the consolidation of voting power in the hands of the existing owners suggests that there the firm will remain largely unchanged after the IPO. IPO Related Issues An initial public offering does create a host of issues that can affect valuation, sometimes tangentially and sometimes directly. In the case of Ferrari, the three issues that merit the most attention are whether the proceeds from the offering will affect value, what the value per share will be, and how the augmentation of voting rights for the existing stockholders will play out.

Conclusion It will be interesting to see this game play out, as the offering gets closer. There is a push to attach a valuation of 11 billion Euros for the Ferrari shares, both because it will get more cash for Fiat from the offering, and more importantly, because the increased value of its remaining holdings in Ferrari will then feed into Fiat's market capitalization. The push may succeed because investors seem eager to buy these shares, at least according to this story, and the price premium will be justified with the argument that Ferrari is a premium brand that caters to the rich. Off to the races! Data Attachments Spreadsheets |

Rishi Chourasia

Oct 31, 2015, 12:55:58 PM10/31/15

to

Reply all

Reply to author

Forward

0 new messages