I need help. GIT doesn't work on my PC Windows 11

578 views

Skip to first unread message

Ana Rosa Soria Kuenneth

Sep 19, 2023, 12:31:53 PM9/19/23

to git-for-windows

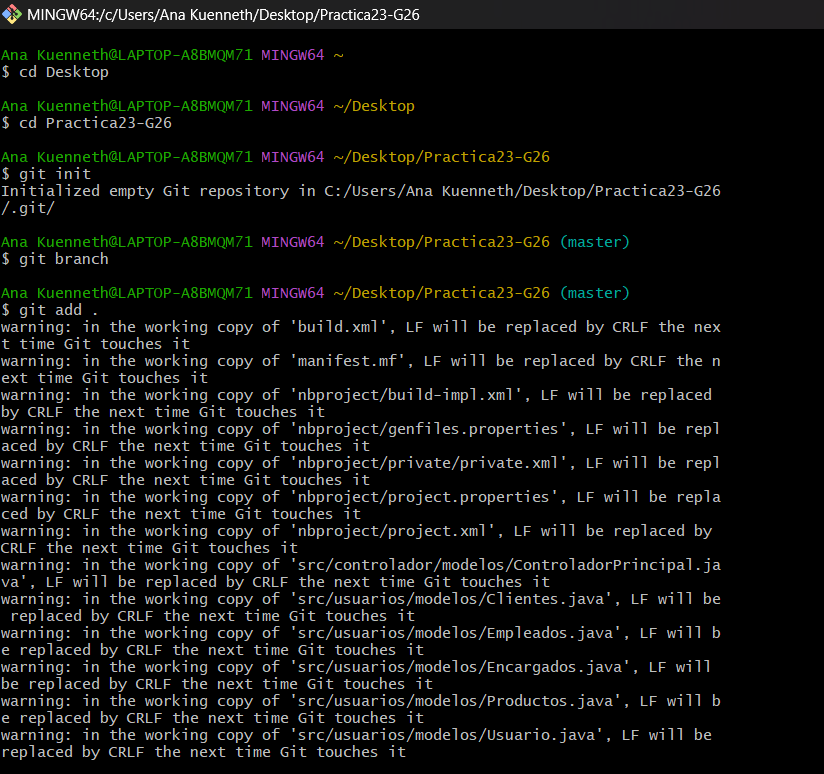

Good night. I'm Ana Kuenneth from Argentina. I don't know what is happenning. I have my pc already formatted and the app GIT reinstalled. Any of the commands don't work, excepting for git init.

Could you help me? It is not a hardware problem, I have already contacted my notebook's company. I have an ASUS X515 with Windows 11 OS.

Wei Hu

Sep 20, 2023, 11:48:08 PM9/20/23

to Ana Rosa Soria Kuenneth, git-for-windows

Did you use command `git config - -global user.name “your name ” `and

`git config - -global user.email “your email ” `after you reinstall GIT?

--

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "git-for-windows" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to git-for-windo...@googlegroups.com.

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/git-for-windows/c60fe228-9384-4b69-88f4-7e8e7659900fn%40googlegroups.com.

Konstantin Khomoutov

Sep 21, 2023, 4:29:19 AM9/21/23

to git-for...@googlegroups.com

On Mon, Sep 18, 2023 at 06:12:43PM -0700, Ana Rosa Soria Kuenneth wrote:

> I don't know what is happenning. I have my pc already formatted and the app

> GIT reinstalled. Any of the commands don't work, excepting for *git init. *

> I don't know what is happenning. I have my pc already formatted and the app

[...]

This is not true. What you're observing, is expected. Well, sort of.

First, to demonstrate actually the same behavior (I'm on a Linux-based OS but

this is irrelevant):

--------------------------------8<--------------------------------

$ cd ~/tmp

tmp$ git init unborn

Initialized empty Git repository in /home/kostix/tmp/unborn/.git/

tmp$ cd unborn/

unborn$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

nothing to commit (create/copy files and use "git add" to track)

unborn$ touch aaa.txt

unborn$ git add aaa.txt

unborn$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: aaa.txt

unborn$ git branch

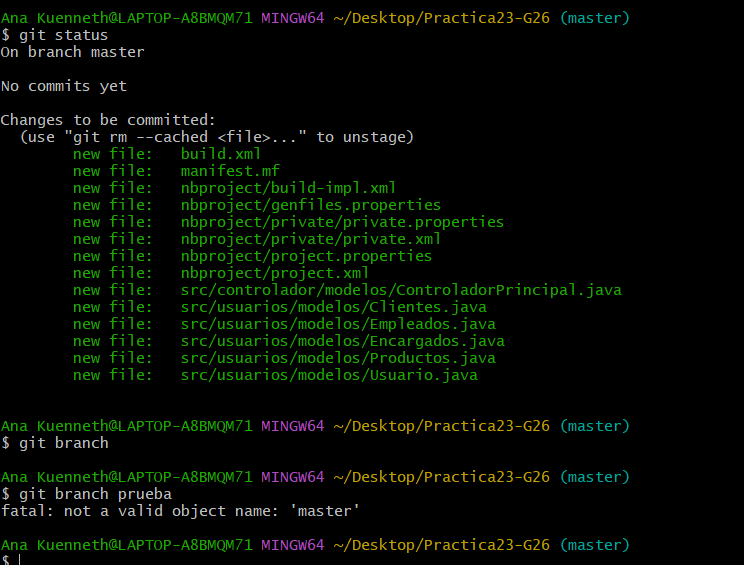

unborn$ git branch prueba

fatal: not a valid object name: 'master'

unborn$

--------------------------------8<--------------------------------

As you can see, I've done mostly the same commands as you did except that you

had already have a bunch of files in a directory which you've decided to turn

into a Git repository, and mine was created afresh (so I need to create a file

to add first). The rest is the same: `git add` and `git status` commands work

in the same way as for you, and the last `git branch` command fails in the

same way as for you.

Since you have made a blanket statement that everything except `git init`

does not work, I have to guess as to what behavior of the examples presented

on your screenshots you consider to be buggy/not working. I guess that you may

be concerned with two points: the "LF will be replaced with CRLF" warning and

the failure of the `git branch` command. Using `git add` might also be a

problem.

Let's start with the `git branch` command.

With it, you have hit a darker corner of Git - an unborn branch. Any branch

in git is basically some name (which you've given to that branch) which points

at a commit - the "tip" (the latest) commit on that branch. That commit refers

to one or more parent commits and so on and so forth - all the way back in the

history of changes. When you record a new commit - using the `git commit`

command which you did not call, - the branch starts pointing at that new

commit. And this happens each time a new commit is recorded.

But there is a situation, where the repository has no commits at all!

The state after `git init` is exactly this. That command created the default

branch named "master", but it does not actually point at any commit because

there is no commits.

Now you call `git branch prueba`, and Git goes like this: it tries to figure

out what commit is at the tip of the current branch - this process is called

"resolving" (of a branch to a commit object), and that fails. The Git

machinery which tried that resolving reported that it failed, and `git branch`

ended up reporting that totally unhelpful error message.

What to do about it?

Well, should you have called `git commit`, before trying to create a new

branch, that should have worked. Now note that you cannot really have a branch

without any commits "on" it (because braches in Git are immaterial, they just

point at commits), so there is not way to create a branch called "prueba"

while staying on (an unborn) branch named "master": that would have required

Git to create a branch which points at nothing which is impossible.

What you can do is to _rename_ the current, unborn branch "master" to

"prueba". To do this, you call

git branch -m prueba

And then you can verify your current unborn branch now has that name:

--------------------------------8<--------------------------------

$ git status

On branch prueba

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

--------------------------------8<--------------------------------

Note that this approach would make the branch "master" did not came into

existence at all. Maybe that was exacty what was needed ("master" is nothing

special, it's just a convention to name a "default" branch), maybe not.

It's up to you to decide.

Second, I have a feeling that you may have missed the point one needs to run

`git commit` to actually "chekpoint" your changes, and instead you might have

thought running `git add` was enough to record your changes.

If my guess is correct, then no, `git commit` is what actually "commits"

a set of changes compiled by calling `git add` (and other commands).

If you're not familiar with this concept, please start with a book and/or a

set of tutorials on Git so we do not waste our precious time on what is

already abundantly covered in the material available on the Internet.

Third, let's deal with that "LF will be replaced with CRLF" warning.

Not sure you're aware of this concept or not, but historically, MS-DOS and

Windows uses the sequence of two bytes, CR (Carriage Return) followed by LF

(Line Feed) to delimit separate lines in plain text files, while operating

systems of the UNIX heritage (these days, it's Linux- and *BSD-based systems,

and Mac OS) use the single byte LF for this purpose¹.

Since Git is frequently used to host projects which should work on any

contemporary OS, it has to somehow deal with the need to have different line

termination sequences in the files it places - "checks out from the

repository" - on the filesystem of a local user's comuter. This is complicated

with the need pick some format to store the contents of these files in the

repository itself. This is a messy task but Git picked a rather sensible

approach: for plain text files, it _defaults_ to storing the platform-native

line-termination sequences in the files it checks out from the repository to

the local user's filesystem, and storing LF in the repository. To say that in

simple words, your local files which you edit have CRLFs in them, and when you

`git add` and then `git commit` these files, Git replaces CRLFs with LFs.

Users on systems of UNIX heritage just get plain LFs in their local files.

But sometimes this does not work as good: over time, many text editing tools

on Windows learned to transparently work with UNIX-style line endings (I

think, these days even Notepad can do that), so it's not uncommon to work on

files with non-Windows line ending and not be aware of that fact.

And it looks like you have hit exactly this case: you have a set of files with

UNIX-style line endings, and you have added them to a Git repository

initialized with the default settings. So Git tells you that it sees such and

such of your files have LF line terminators, it understood that, but since Git

does not store any sort of "line termination property" along with each file,

as soon as Git will need to place some historical content into one of these

files, that content will have CRLFs, not LFs.

Exactly what to do about that, is an open-ended question.

If you're sure, all your files have UNIX-style line endings, and you're fine

about this (seems you are), after initializing the repository but before

adding any files and recording a commit, configure the repository to use

UNIX-style line endings by running²

git config --local --add core.eol lf

If you want to mark just specific files as having UNIX-style line endings,

you'd need to use the so-called "Git attributes" file - run

`git help attributes` to learn more.

> [image: Captura de pantalla 2023-09-18 221123.png]

> [image: Captura de pantalla 2023-09-18 221136.png]

and all the shells on Windows, including Git Bash, support selecting and

copying text they display read

<https://meta.stackoverflow.com/a/285557/720999> to learn these reasons.

Footnotes.

¹ The names of these bytes, and their codes are defined by what is known

as ASCII. If you're not aware of what it is, read

<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ASCII>

² Run `git help config` to learn more.

Johannes Schindelin

Sep 21, 2023, 8:05:08 AM9/21/23

to Ana Rosa Soria Kuenneth, git-for-windows

Hi Ana,

you need to commit the changes before there really is a branch. Please

follow Git tutorials such as https://git-scm.com/docs/gittutorial (in

particular "Importing a new project").

Ciao,

Johannes

On Mon, 18 Sep 2023, Ana Rosa Soria Kuenneth wrote:

> Good night. I'm Ana Kuenneth from Argentina. I don't know what is

> happenning. I have my pc already formatted and the app GIT reinstalled. Any

> of the commands don't work, excepting for *git init. *

you need to commit the changes before there really is a branch. Please

follow Git tutorials such as https://git-scm.com/docs/gittutorial (in

particular "Importing a new project").

Ciao,

Johannes

On Mon, 18 Sep 2023, Ana Rosa Soria Kuenneth wrote:

> Good night. I'm Ana Kuenneth from Argentina. I don't know what is

> happenning. I have my pc already formatted and the app GIT reinstalled. Any

> Could you help me? It is not a hardware problem, I have already contacted

> my notebook's company. I have an ASUS X515 with Windows 11 OS.

>

> [image: Captura de pantalla 2023-09-18 221123.png]

> [image: Captura de pantalla 2023-09-18 221136.png]

>

> my notebook's company. I have an ASUS X515 with Windows 11 OS.

>

> [image: Captura de pantalla 2023-09-18 221123.png]

> [image: Captura de pantalla 2023-09-18 221136.png]

>

Reply all

Reply to author

Forward

0 new messages