To macerate or not...

1,222 views

Skip to first unread message

Ray Blockley

Nov 7, 2021, 5:09:58 AM11/7/21

to Cider Workshop

I'm interested in the views of makers as to the reasons why or why not they macerate apples & pears after milling/scratting.

I've always assumed that macerating the pulp for a few hours / overnight / days (or more?) was for one or two of the following main reasons:

1. To improve juice yield.

2. To remove excess tannin (ie tannic perry pears or certain full bitter apples).

3. As a prelude to / part of Keeving.

3. As a prelude to / part of Keeving.

As the bulk of my ciders are made with a mix of dessert & culinary apples, I don't tend to macerate as I try to hang on to whatever tannins are available in the fruit.

Some makers I know macerate everything routinely so I'm wondering if I'm missing something or need to update my knowledge...?

Thanks, Ray.

Nottingham UK

Thanks, Ray.

Nottingham UK

Andrew Lea

Nov 7, 2021, 6:08:40 AM11/7/21

to cider-w...@googlegroups.com

Essentially by macerating you are allowing a lot of biochemistry to take place in which native fruit enzymes react with native fruit components in an uncontrolled way that doesn’t happen in intact fruit. Many of these systems are bound to cell walls (pulp), hence things happen which would not happen in the juice by itself.

The three main systems I’m aware of are pectin breakdown to increase yield and to solubilise more pectin when keeving, polyphenol oxidation which can remove tannins onto the pulp if there is sufficient contact with oxygen, and lipid oxidation which allows fatty acids in the apple skin to break down and produce new flavour precursors hence improving the aroma complexity during fermentation. In addition you can also increase some aroma precursors (eg octanediols) by glycosidase action which liberates them from a bound and non-volatile form. These can then transform into interesting aroma components such as dioxolanes during fermentation.

But like you I’m not sure there is any advantage to maceration on a routine basis for most people. Typically I only did it when keeving, when of course I was looking for the greatest flavour complexity anyway and prepared to put in the effort. It’s an extra step which lengthens the process, requires increased storage capacity, and I’m not sure it’s necessarily justified by results. We certainly never did it as routine in my Long Ashton days. However, I confess I have never done a controlled trial. Other people may have more evidence-based views ;-)

Andrew (back to the apple harvesting now ....)

Wittenham Hill Cider Portal

www.cider.org.uk

www.cider.org.uk

On 7 Nov 2021, at 10:08, Ray Blockley <raymond...@gmail.com> wrote:

--

--

Visit our website: http://www.ciderworkshop.com

You received this message because you are subscribed to the "Cider Workshop" Google Group.

By joining the Cider Workshop, you agree to abide by our principles. Please see http://www.ciderworkshop.com/resources_principles.html

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "Cider Workshop" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to cider-worksho...@googlegroups.com.

To view this discussion on the web, visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/cider-workshop/CAO7CN4mjOCqwgpvr85spQ3b9k6i2iO8yOpBbH6UD6i9MYGMtrg%40mail.gmail.com.

Ray Blockley

Nov 7, 2021, 6:28:45 AM11/7/21

to Workshop-Cider

Thanks for that, Andrew.

Adds meat to the bones.

Can I just clarify that by "...polyphenol oxidation which can remove tannins onto the pulp if there is sufficient contact with oxygen..." you are *decreasing* the tannin content in the resultant cider or perry? Just to be sure.

Thanks, Ray.

To view this discussion on the web, visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/cider-workshop/F4DD7BC3-733A-4514-8F83-626173A89CED%40cider.org.uk.

Andrew Lea

Nov 7, 2021, 11:07:24 AM11/7/21

to cider-w...@googlegroups.com

“Meat on bones” ... I like that!

Yes, in nearly all cases, maceration of apple pulp leads to a decrease in the tannin content of the resultant juice and cider. That’s because tannins are oxidised and adsorbed irreversibly (tanned) to the pulp, leading to a net loss in the juice. However, this may not be intuitively obvious because the soluble colour can increase at the same time that the total tannin decreases. So because of that visual change, people may mistakenly think the tannin is increasing, but actually it isn’t. This is covered in some detail in my discussion with Gabe Cook here, from about 33 minutes in https://youtu.be/OezB-pubhZ4 (The sound quality is rather poor but subtitles may help though since they are auto-generated there are some rather odd renderings of technical terms!)

The only circumstance where maceration might increase the soluble tannin level is if you specifically extracted the apple skins with hot water or alcohol, or fermented on the skins in the same way that red wines are made. But this is not what is normally understood by maceration.

Andrew

On 7 Nov 2021, at 11:27, Ray Blockley <raymond...@gmail.com> wrote:

To view this discussion on the web, visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/cider-workshop/CAO7CN4n8%2BD4eD3H52no7q_XBeCabcQq%3DqN%2Bfe3J%3DuCuDv7r0SA%40mail.gmail.com.

Claude Jolicoeur

Nov 7, 2021, 11:24:01 AM11/7/21

to Cider Workshop

I did an interesting experiment a few years ago, from juice of Banane amère, a very bitter natural seedling that grows on my property.

What I did is that I extracted 2 juice samples from the same lot of apples. One was obtained with a centrifugal extractor, so a very rapid extraction, and the other was obtained by standard pressing with a rack-and-cloth press after pulp maceration.

Both samples were analyzed at Cornell University in NY for tannin using the Folin–Ciocalteu procedure.

Results for both samples were:

- sample obtained with centrifugal extractor: 4.1 g/L as gallic acid

- sample obtained by pressing after maceration: 1.8 g/L

Andrew Lea

Nov 7, 2021, 11:37:10 AM11/7/21

to cider-w...@googlegroups.com

Thanks for that observation Claude.

When I worked on the chemistry of oxidising tannins at Long Ashton back in the 1970s I set up a centrifugal juice extractor with a nitrogen purged inlet so that the apple juice would be extracted quickly with absolutely no oxidation at all. It was water white and very high in tannin compared to the control fruit which was normally extracted and of course yellow / brown in colour. I no longer have the notebooks from that time easily available but I think the figures you quote would be entirely consistent with my observations then.

Btw if anyone is confused by the measurement “as gallic acid” this is a standard frequently used in polyphenol work. Gallic acid is an acid but more importantly it is also a stable natural polyphenol and so it is often used “as gallic acid equivalents - GAE” to express measured tannin levels. This has nothing to do with its acidity. Gallic acid scarcely occurs in apples except at very low levels but it is widely used to express tannin measurements in foods such as tea, wine, ciders etc.

Andrew

On 7 Nov 2021, at 16:22, Claude Jolicoeur <cjol...@gmail.com> wrote:

To view this discussion on the web, visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/cider-workshop/1b317a04-0782-40c6-9897-b80658df2b3fn%40googlegroups.com.

Ray Blockley

Nov 7, 2021, 2:03:06 PM11/7/21

to Workshop-Cider

Thank you very much Andrew & Claude.

Great explanations & examples - much appreciated.

Ray.

To view this discussion on the web, visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/cider-workshop/9CA3CD66-8E81-4E7B-A340-6AEAB6FA2B24%40cider.org.uk.

Ian Shields

Nov 8, 2021, 6:11:11 AM11/8/21

to cider-w...@googlegroups.com

To what extent would leaving the pulp in the (rack and cloth) press for a number of hours before pressing go someway to achieving the advantages of macerating?

Ian

On Sun, 7 Nov 2021, 11:08 Andrew Lea, <ci...@cider.org.uk> wrote:

To view this discussion on the web, visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/cider-workshop/F4DD7BC3-733A-4514-8F83-626173A89CED%40cider.org.uk.

Johan Strömberg

Nov 8, 2021, 7:54:03 AM11/8/21

to cider-w...@googlegroups.com

I did overnight macerated (15 - 20 hours) some of the pulp for the first time in my cider making history in this year and found the juice was somewhat richer in taste than direct pressed. However when juice is now ferment close to dryness there ain't really that much of differences. Also I did not get better juice yield in my basket press. I think the maceration time should be way longer (days or even weeks) to get some differences for dry cider with apples and It's a really different game with grapes esp in white wines where even 24 hours will make significant differences.

-Johan

To view this discussion on the web, visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/cider-workshop/CA%2B4GERuEih-ZVFBD%2BySwwFSwo4VN6LTDkSLVksUdDLQncKC6Pw%40mail.gmail.com.

Johan Strömberg

Nov 8, 2021, 8:03:25 AM11/8/21

to cider-w...@googlegroups.com

I forgot to mention that the speed of natural yeast fermentation (no added SO2) has been really fast & vigorous and I can't figure out other clear reason compared other vintages than extended maceration time so maybe that is one significant change. Is it good or bad? Hard to say at this point.

luis.ga...@gmail.com

Nov 8, 2021, 9:40:12 AM11/8/21

to Cider Workshop

The only circumstance where maceration might increase the soluble tannin level is if you specifically extracted the apple skins with hot water or alcohol, or fermented on the skins in the same way that red wines are made. But this is not what is normally understood by maceration.

Interesting! I tought tannin in aple skin were not soluble and there was no way you could get these. Do we know the amount of tannin that can be obtained that way? Some new trendy cideries are doing this here (fermenting with pulp) and I always tought they were simply importing a wine technique to their cidery assuming that they could get the same results than they would with grape.

Tom Bugs

Nov 9, 2021, 6:01:14 AM11/9/21

to Cider Workshop

From another of the CiderCon videos that Andrew pointed to (looking forward to watching the others!) - I watched the Keeving one with Alan & Anne Bland of Templar Cider. They do a lot of keeving but noted that their pressing is done by travelling press, so they don't have the scope to macerate. Two interesting points - i) that Alan didn't note any issue with not leaving the pulp to macerate when keeving (chapeau often forms on the juice used for distilling even without the keeving additions) & ii) he mentioned a specific yeast variety that apparently only gets to work at very, very low alcohol levels, so really only has a chance in the maceration period, not after pressing. Anyone else heard about this?

Andrew Lea

Nov 9, 2021, 10:42:22 AM11/9/21

to cider-w...@googlegroups.com

& ii) he mentioned a specific yeast variety that apparently only gets to work at very, very low alcohol levels, so really only has a chance in the maceration period, not after pressing. Anyone else heard about this?

Adam wasn’t very explicit but I think all he was referring to was the group of apiculate i.e. non-Saccharomyces yeasts such as Hanseniospora / Kloeckera. Any good wine or cider textbook will explain that these yeasts are the first to get going in a wild succession but they have limited alcohol tolerance and pretty much die out at alcohol levels of 2-4%, after which the wild Saccharomyces take over. The point about the apiculate yeasts is that they produce more short chain esters than the Saccharomyces and this is what contributes character to a wild yeast fermentation.

On 9 Nov 2021, at 10:59, Tom Bugs <bugb...@gmail.com> wrote:

From another of the CiderCon videos that Andrew pointed to (looking forward to watching the others!) - I watched the Keeving one with Alan & Anne Bland of Templar Cider. They do a lot of keeving but noted that their pressing is done by travelling press, so they don't have the scope to macerate. Two interesting points - i) that Alan didn't note any issue with not leaving the pulp to macerate when keeving (chapeau often forms on the juice used for distilling even without the keeving additions) & ii) he mentioned a specific yeast variety that apparently only gets to work at very, very low alcohol levels, so really only has a chance in the maceration period, not after pressing. Anyone else heard about this?

To view this discussion on the web, visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/cider-workshop/fe74944a-020c-4b9e-8a4f-6abcb6cb46a4n%40googlegroups.com.

Eric Tyira

Nov 9, 2021, 11:02:37 AM11/9/21

to cider-w...@googlegroups.com

Andrew,

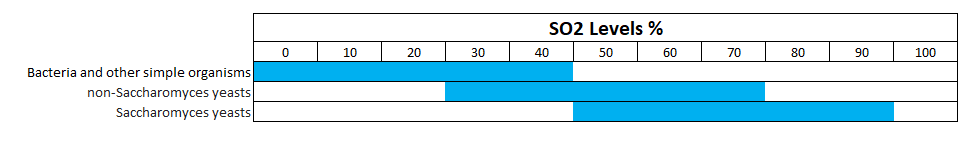

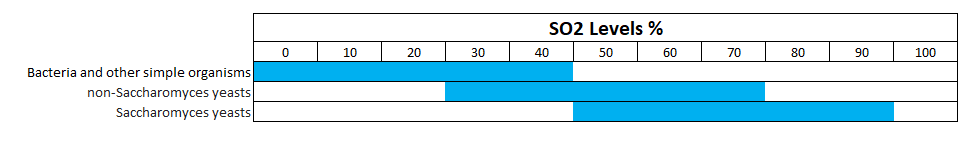

I don't want to hijack the thread, but I have a question right along these lines. For wild fermentations we talk of using roughly 50% SO2 levels that we would normally use to help keep unwanted microbes at bay. Are the non-Saccharomyces yeasts rendered inert when using roughly 50% SO2 additions? Or will they fall victim at higher SO2 levels?

I know this probably isn't black and white because of the variations in microbes, PH, SO2 levels, etc., but just in general terms.

If we were to put it into visual form, would it look something like this COMPLETELY MADE UP(!) example?

Eric

To view this discussion on the web, visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/cider-workshop/CFAC1CDD-2EC2-43E8-BA65-75C88EE2A37F%40cider.org.uk.

Ray Blockley

Nov 10, 2021, 5:10:10 AM11/10/21

to Cider Workshop

Hi Andrew / Claude.

Another Tannin & air / oxygen contact thought that you may be able to help with:

At what point does the tannin in solution (ie post maceration & pressing) become "fixed"...?

Am I right in assuming that sloshing raw juice around & pouring from ie: container to container, could result in more polyphenols bonding with oxygen & therefore being "lost"?

Am I right in assuming that sloshing raw juice around & pouring from ie: container to container, could result in more polyphenols bonding with oxygen & therefore being "lost"?

Is there for example an alcohol level where the tannin is perhaps dissolved by or bonded to the alcohol & therefore fixed into the final cider or perry...?

Thanks for all your help, this discussion is helping me think about what I do with frequently very low tannin fruit.

Ray.

To view this discussion on the web, visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/cider-workshop/9e849534-ac12-4778-bef8-6c8145255547n%40googlegroups.com.

Andrew Lea

Nov 10, 2021, 8:19:08 AM11/10/21

to cider-w...@googlegroups.com

The greatest immediate loss of tannins is when you have pulp and air present together. The oxidising enzyme (PPO) is in itself mostly bound to the pulp and the oxidised polyphenols are then bound straight into the pulp as well. If you want to stop this oxidation you can do the milling under nitrogen or trickle SO2 solution over the pulp or do everything very cold (this is also a trick used by some white wine makers). That way you get an unoxidised juice. But these techniques may not prove to be realistic and, although you can conserve tannin that way, you don’t get much development of colour or aroma.

The PPO enzyme is no longer active after a few hours and once you have clear juice there is relatively little change in the tannin level thereafter. This is shown as the top (dotted) line in Slide 19 here http://www.cider.org.uk/phenolics_in_cider_apples.pdf. If you did a lot of juice aeration you could probably lose a little more tannin, which will be by self-polymerisation and eventually this will bind to soluble protein and drop out in the lees. But this is a relatively minor effect.

During yeast fermentation there are some reductive mechanisms which actually liberate a little more tannin back into solution. But generally the effect of fermentation on the tannin is pretty neutral. In the longer term (months of cider maturation) there may be minor loss of tannin but mostly as in red wine it’s a slow (chemical not enzymic) polymerisation of small soluble tannins to larger soluble ones, hence a gradual shift in flavour profile from bitterness to astringency but not necessarily much loss in overall tannin.

I hope this helps. It’s not an easy one to get to grips with!

Andrew

Wittenham Hill Cider Portal

www.cider.org.uk

www.cider.org.uk

On 10 Nov 2021, at 10:14, Ray Blockley <raymond...@gmail.com> wrote:

To view this discussion on the web, visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/cider-workshop/CAO7CN4m9z2HhfCw5GmZF43%2B9-YYeVGDEzJfhFS9EDLEM-9Vapg%40mail.gmail.com.

Ray Blockley

Nov 11, 2021, 2:57:52 AM11/11/21

to Workshop-Cider

Thanks again, Andrew. I feel much more informed about what's going on now.

Ray.

To view this discussion on the web, visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/cider-workshop/2B54FFA8-2551-4B90-BA86-39928DD65E5E%40cider.org.uk.

Andrew Lea

Nov 11, 2021, 6:16:12 PM11/11/21

to cider-w...@googlegroups.com

I think your image is a pretty good summary really (though one might quibble endlessly where the blue bars should be set). But I think you have the generally accepted hierarchy correct. Of course there are glaring exceptions eg Brettanomyces and Lactobacillus plantarum are often quoted as being pretty SO2 tolerant, but the general drift is what has become accepted by wine and cider scientists over the last 50 years or so.

100% on your diagram pretty much corresponds to 1 ppm of molecular SO2 which is the most objective way of assessing the effective sulphite level.

Andrew

Wittenham Hill Cider Portal

www.cider.org.uk

www.cider.org.uk

On 9 Nov 2021, at 16:01, Eric Tyira <secretc...@lostruinswinery.com> wrote:

Andrew,I don't want to hijack the thread, but I have a question right along these lines. For wild fermentations we talk of using roughly 50% SO2 levels that we would normally use to help keep unwanted microbes at bay. Are the non-Saccharomyces yeasts rendered inert when using roughly 50% SO2 additions? Or will they fall victim at higher SO2 levels?I know this probably isn't black and white because of the variations in microbes, PH, SO2 levels, etc., but just in general terms.If we were to put it into visual form, would it look something like this COMPLETELY MADE UP(!) example?

<image.png>Eric

To view this discussion on the web, visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/cider-workshop/CAKZkS6DPMQ0pXBgxTjU9M7K4xshsz5be4oygxVwh%3DVuR2ZmCkA%40mail.gmail.com.

Reply all

Reply to author

Forward

0 new messages