Putting the electric harness on old dams

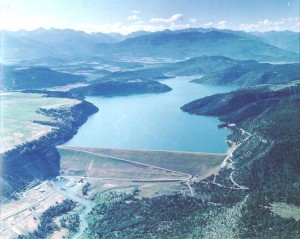

- Pueblo Dam, located on the

Arkansas River, is among several dams in the Rocky

Mountains targeted for installation of hydroelectric

turbines.

Photo/Bureau of Reclamation

State and federal incentives together producing new power from old dams

by Allen Best

As with most smaller dams from that era, no hydroelectric turbines were installed in Pueblo Dam when it was constructed during the early 1970s. It’s located in central Colorado, the silvery summit of Pikes Peak in the distance, impounding the Arkansas River as it meanders onto the Great Plains.

The dam’s 191 feet height provides what hydrologists call head, a prerequisite for making large amounts of electricity. Absent, though, are large volumes of water.

Now, with strong financial and other incentives from both the state and federal governments, dam operator Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District seeks to install turbines sufficient to allow production of 7 megawatts.

Five such retrofits in the West have occurred since 2008. Pueblo and 18 others are in the pipeline. Many are in Colorado, which has emerged as a model for how to encourage the retrofitting of smaller, older dams.

Retrofitting Colorado dams and canals

- Ridgway Reservoir (8 MW): completed 2014

- Carter Lake (2.6 MW): completed 2013

- South Canal Drops 1 and 3 (7.5 MW): completed 2013

- Lake Granby (1.2 MW): underway

- Pueblo Reservoir (7 MW): underway

- Shavano Falls (2.8 MW): underway

- South Canal Drop 2 (1 MW): underway

Michael Pulskamp, who oversees the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s lease-of-power-privileges program from an office in suburban Denver, says the 2005 Energy Bill required resource assessments of federal water infrastructure but the Obama administration delivered the push.

Those studies found great cumulative potential. A 2011 study concluded that one million megawatts of annual production of electricity could be delivered if just the 70 most promising dams, diversion structures, and tunnels were developed. The study had screened 530 federal sites.

Colorado, Utah, Montana, Texas, and Arizona have the most sites with hydropower potential.

“That study really laid out that we weren’t tapped out in terms of hydropower potential,” says Pulskamp.

Another federal assessment of 373 irrigation canals, tunnels, and other conduits in 13 Western states found another potential 103.6 megawatts of generating capacity.

Even if all the 1.1 million potential megawatts identified in the two studies get built, the capacity will be dwarfed by existing dams in the West. Grand Coulee Dam, completed on the Columbia River in 1941, produces 21.5 million megawatts annually, tops in the West. Glen Canyon Dam, on the Colorado River, can produce 3.8 million megawatts, followed closely by Hoover Dam with 3.7 million.

Shasta Dam, in California, can produce 1.9 million megawatts and Davis Dam, on the Colorado River in Arizona, produces 1.1 million megawatts.

Colorado’s largest hydroelectric production comes from the three dams on the Gunnison River in what is called the Aspinall Unit. Together, they can produce 826,000 megawatts annually. Hydroelectric capacity installed in several components of the Colorado Big-Thompson diversion project can collectively produce 413,000 megawatts.

In comparison, new turbines on Utah’s Jordanelle Dam can produce 39,000 megawatts annually while Colorado’s Ridgway Dam, which went on line last May, can produce 22,000 megawatts annually.

Pueblo will produce even less, 19,700 megawatts annually. Southeastern Water was prodded into taking on the project only after the Bureau of Reclamation specifically solicited proposals.

“We were afraid if we didn’t pursue it, a private entity might come and develop the project,” says Kevin Meador, project manager for Southeastern Colorado Water. The Pueblo-based agency administers water diverted to the Arkansas from the Aspen area under federal sponsorship in the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project.

Colorado’s state government has provided both financial incentives and a market for sale of renewable energy. One of the incentives is a 2 percent loan at 30 percent from the Colorado Water Conservation Board. “That is a huge factor in making this project feasible,” says Meador.

The Colorado Water Resources and Power Development Authority also provides 20-year loans of 2 percent.

In setting a 30 percent renewable portfolio standard for investor-owned utilities and now a 20 percent standard for Tri-State Generating & Transmission, Colorado has created a market for power from smaller dams. No buyers for the electricity from Pueblo have been lined up, but Meador says his agency needs to get 3.5 to 4 cents per kilowatt hour to make the numbers work.

If this were Massachusetts or Hawaii, where electricity prices to consumers run up to 25 cents per kilowatt hour, that would be an easy sell. But in the Rocky Mountains, energy has historically been relatively cheap, observes Meador, “and these hydro projects are capital intensive. They are very expensive up front.”

Seven percent of all U.S. electricity comes from hydropower. In Colorado, it’s 4 percent. Pulskamp says that the greatest hydroelectric potential lies in further harnessing the slow-moving but vast quantities of water in the Mississippi River and its tributaries. His agency, however, has little oversight there.

Kurt Johnson, president of the Colorado Small Hydro Association, says Colorado could serve as a model for other states. He points to efforts begun in the administration of former Gov. Bill Ritter to surmount an often clunky, discouraging federal permitting process. Even more important, Colorado has sweetened incentives with low-cost, long-term loans. Finally, last year it lowered regulatory hurdles.

Two key federal laws passed by Congress in 2013 simplified the federal regulatory process. One law specifically targeted Bureau of Reclamation facilities. Johnson’s organization now seeks to lower the hurdle for other existing but non-federal facilities that must get approval from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

Despite the recent growth, however, hydroelectric remains just a small part of new electrical generating capacity, both in the West and nationally. In 2015, gas was responsible for the most new generating capacity, followed by wind and solar. Hydro was just 1 percent of total national production.

The spillway at Granby Dam

rarely gets used, because nearly all water upstream is

diverted to eastern Colorado.

Photo/U.S. Bureau of Reclamation

Yet even with just trickles of water, hydro power now makes sense financially. Consider Granby Dam, which plugs the Colorado River a few dozen miles from the river’s origins in Rocky Mountain National Park. The dam is 298 feet tall, providing plenty of head. Like Pueblo, it lacks water: just 20 cubic feet per second of water gets released during winter months, as required for environmental purposes, and 75 cfs during summer, except in the biggest of runoff years. The rest gets diverted to cities and farms east of the Continental Divide.

With so little water, Granby can generate just 1/800th of the total production of Hoover Dam. That small production, along with competition from cheap power, is why turbines were never installed when the dam was built from 1941 to 1950.

“Probably power sale rates were next to nothing,” says Carl Brouwer, a project manager for Northern Water, the water agency that distributes Colorado-Big Thompson water to the Boulder-Greeley-Fort Collins area.

As with Pueblo, Northern Water had first shot at obtaining the lease to produce power and did so to preclude shared operations. Northern was aware of at least one other bidder, says Brouwer.

Granby also needed the state’s $5.1 million loan at 2 percent interest is crucial in moving the $5.8 million project forward. “That low-interest loan is what makes this project feasible,” says Brouwer.

A smaller revenue stream comes from sale of the environmental attributes of the energy through a financial device called renewable energy certificates, or RECs. Purchaser was Tri-State Generation & Transmission.

Annual revenues, projected to be $375,000, will pay off debt and operations during the first 30 years. But unlike coal-fired power plants, the supply of fuel will always be free.