Fwd: [ontolog-forum] Higgs bosons, Mars missions, and unicorn delusions

joseph simpson

From: John F Sowa <so...@bestweb.net>

Date: Tue, Mar 27, 2018 at 9:00 AM

To: ontolog-forum <ontolo...@googlegroups.com>

I came across a paper with the above title. The authors claimed

that an ontology should distinguish between imaginary and actual

entities: http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-833/paper24.pdf

Unfortunately, it's impossible to make that distinction. Every

entity in science, engineering, business, and the law is imaginary

(AKA hypothetical) before it has been observed or built or proved

or planned or decided -- and often afterwards.

Even for a novel, the characters may be imaginary, but the ontology

is the same as the ontology for everyday life.

Sometimes, realistic fiction may make important contributions to

methods of logic and ontology. For example, the methods of reasoning

by Sherlock Holmes were the inspiration for modern forensic methods

in police departments around the world.

As for Higgs bosons, Mars missions, and unicorns, there is no

fundamental difference between them and neutrinos, moon missions,

or any animal that is suspected, but not yet observed.

The distinction between hypothetical and actual belongs to the

methodology for designing and selecting modules for any particular

application. The domain experts should make that decision.

Some examples:

1. There is no difference in reasoning about birds before and after

they have been discovered, gone extinct, and later rediscovered

after somebody heard their song in some remote forest.

2. There is no difference in the methods for simulating an airplane

design before it has been built, while it's being built, and after

it's flying in the sky. If the funding is cut, it may never be

built. But that distinction has no influence whatsoever on the

logic, ontology, and methods of reasoning and computation about

the subject.

3. In science, there is no such thing as a finished, perfect,

universally accepted theory. Even a long-rejected theory, such

as phlogiston, survived for a long time because it made useful

predictions. The 19th century theories of heat replaced it

because they made better predictions. Then statistical mechanics

made even deeper analyses, but it did not replace the 19th c

theories, which are still used today in practical applications.

4. Even theories that are known to be false in detail, such as

Newtonian mechanics and other non-relativistic and non-quantum

theories, are still the most widely used -- because the error

bounds in measurement are often much greater than the limitations

of the theories.

5. Finally, the overwhelming amount of matter and energy in the

universe is *dark* -- i.e., unobservable except for their

influence on a galactic or intergalactic scale. According

to the above paper, every theory of science or engineering

would have to be labeled fictional or imaginary.

Fundamental principle: There is a continuum between theories and

ontologies based on known, unknown, hypothetical, confirmed, planned,

imagined, or fictional entities. The distinction is important for

making practical decisions. But it's not a binary distinction.

John

--

All contributions to this forum are covered by an open-source license.

For information about the wiki, the license, and how to subscribe or unsubscribe to the forum, see http://ontologforum.org/info/

--- You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "ontolog-forum" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to ontolog-forum+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

For more options, visit https://groups.google.com/d/optout.

----------

From: joseph simpson <jjs...@gmail.com>

Date: Tue, Mar 27, 2018 at 9:23 AM

To: "mjs...@gmail.com" <mjs...@gmail.com>

“Reasonable people adapt themselves to the world.

Unreasonable people attempt to adapt the world to themselves.

All progress, therefore, depends on unreasonable people.”

- George Bernard Shaw

----------

From: <mbroch...@gmail.com>

Date: Tue, Mar 27, 2018 at 1:32 PM

To: ontolo...@googlegroups.com

Nice claims. Any arguments?

Best,

Mathias

Sent from my iPhone

----------

From: <mbroch...@gmail.com>

Date: Tue, Mar 27, 2018 at 1:36 PM

To: ontolo...@googlegroups.com

Let me recall my previous message.

Sent from my iPhone

> On Mar 27, 2018, at 9:00 AM, John F Sowa <so...@bestweb.net> wrote:

>

----------

From: <hpo...@verizon.net>

Date: Tue, Mar 27, 2018 at 5:50 PM

To: ontolo...@googlegroups.com

John,

You may recall our email exchanges from several years ago about what I referred to as "conceptual realities". Some examples are things like school districts, police or voting precincts, campuses, air space restricted areas, and the like. There are typically no physical manifestations of such entities - you could walk into or out of one and never notice it, because the geospatial boundaries of such entities rarely have any readily recognizable physical manifestations. Yet we treat them as real entities in many operational contexts.

There are also entities such as fleets, units, facilities and the like. These are typically aggregates of physical objects based on ownership or some other form of association that has no inherent physical manifestation. Although there is often some logo, insignia, vehicle number or other physical marking that identifies the individual objects as being members of the aggregate entity, a common real world problem is how to detect, track, and represent such aggregate entities, especially if, for whatever reason, the individual entities are not physically marked as members/associates of the aggregate entity. Some possible examples are a disaster relief task force made up of multiple private and government entities, or something as simple as a protest march - e.g., who are the protestors and who are the bystanders or, say, crowd security elements. Even the members of the Ontolog Forum could fit this category - we don't carry ID cards or wear distinctive berets last I checked.

Hans

----------

From: Ravi Sharma <drravi...@gmail.com>

Date: Tue, Mar 27, 2018 at 7:26 PM

To: ontolog-forum <ontolo...@googlegroups.com>

----------

From: John F Sowa <so...@bestweb.net>

Date: Wed, Mar 28, 2018 at 12:11 AM

To: ontolog-forum <ontolo...@googlegroups.com>

Hans and Ravi,

I strongly agree with Hans. See below for my response to his

note from February 12th of this year.

HP

You may recall our email exchanges from several years ago about

what I referred to as "conceptual realities". Some examples are

things like school districts, police or voting precincts, campuses,

air space restricted areas, and the like. There are typically no

physical manifestations of such entities...

The point I would add is that there are very important physical

manifestations. They're called signs. Every sign is interpreted

by minds (possibly with some mental aid, such as languages, pictures,

diagrams, paper and pencil, computers...). Peirce used the term

'quasi-mind' for non-human agents, which could include robots.

But every sign has a perceptible "mark". When it's interpreted

by some agent (human, animal, or robot) the result is some physical

action, which may generate further signs.

RS

my question is what part of Logic or any other test can we

perform to possibly separate ontologies that pertain to known

or real domains (I cant find better words) vs some illogical

non-plausible (based on current knowledge) ontologies that

might be purely imaginary

Ravi, I'll continue to be polite, so I won't say what I think of

that paper. But "delusional" is mild compared to what I would say.

Those authors used the word 'unicorn' to deprecate the work by

scientists and engineers who are doing advanced R & D (Higgs boson

and Mars missions, for example). They used the term 'unicorn

delusions'. But they were not talking about unicorns. They were

implying that that you, I, and all the scientists, engineers,

mathematicians, and programmers are deluded in thinking that we're

doing something real.

But they have no understanding of logic. For example, the modal

logics based on possible worlds often use axiom S5, which implies

that every possible world has *exactly* the same ontology as the

real world. Axiom S4 would allow some variation in the laws of

different worlds, but most of the laws would be the same.

Their philosophy is nominalist, *not* realist. It implies that the

laws of science are nothing but summaries of data. That reduces

science to the study of meter readings.

Alonzo Church, a logician and philosopher I highly respect, gave a

lecture at Harvard, where he ridiculed the nominalists, such as Quine

who was in the audience: http://jfsowa.com/ontology/church.pdf

For an article about the limitations of nominalism, see Signs,

processes, and language games: http://jfsowa.com/pubs/signs.pdf

I'll say more when I get back from San Diego.

John

-------- Forwarded Message --------

Subject: Re: [ontolog-forum] Models and symbol grounding

Date: Wed, 14 Feb 2018 09:54:35 -0500

From: John F Sowa

On 2/13/2018 12:47 PM, Hans Polzer wrote:

The one thing I would add to this discussion is the role that

human institutions play in establishing grounding and associated

frames of reference and standards.

Human institutions or social organizations are extremely important.

They're based on shared intentions among a group of people for some

activity or system of activities.

There are many types of such institutions, with varying degrees of

formality and sanction, including academic, government, standards

bodies/NGOs, corporations, industry associations, and informal

interest groups.

Yes. And the intentions of the people involved are always indicated

by a sign: a contract, treaty, constitution, bylaws, announcement,

ceremonies... Some institutions, such as the Mafia, have rules

about signs: Don't write what you can say, don't say what you can

wink, and don't wink what you can nod. Vinnie "The Chin", for

example, would stroke his chin as a sign for "Do it".

these institutions serve to convert the arbitrary and subjective

conventions and frames of reference into something that is viewed

as at least quasi-objective by individuals and institutional entities

who cite or otherwise subscribe to them.

It's the publicly observable sign and the accompanying action that makes

them objectively known. That action may be as informal as a handshake,

or it may be a formal ceremony: a wedding, swearing on a Bible, or

smoking a peace pipe. A handshake with witnesses can be used as

evidence in a court of law.

These boundaries are often vague, implicit and difficult to discover

because historically there has been no real need or capability to do

so in a machine-processable way.

People recognized the need thousands of years ago. The Sumerians

invented cuneiform around 4000 BC to list the goods carried by

their caravans and record what was exchanged for those goods.

the root cause of most interoperability issues that arise in our

increasingly connected world.

People and their institutions have always been connected to other

tribes with different institutions. The need for cooperation,

trade, and resolving conflicts required shared conventions and

methods of communication. The WWW is just our latest version

of cuneiform and camel caravans.

----------

From: Marcel Fröhlich <marcel....@gmail.com>

Date: Wed, Mar 28, 2018 at 1:50 AM

To: ontolo...@googlegroups.com

Relative onticity

Contextual emergence has been originally conceived as a relation between levels of descriptions, not levels of nature: It addresses questions of epistemology rather than ontology. In agreement with Esfeld (2009), who advocated that ontology needs to regain more significance in science, it would be desirable to know how ontological considerations might be added to the picture that contextual emergence provides.

A network of descriptive levels of varying degrees of granularity raises the question of whether descriptions with finer grains are more fundamental than those with coarser grains. The majority of scientists and philosophers of science in the past tended to answer this question affirmatively. As a consequence, there would be one fundamental ontology, preferentially that of elementary particle physics, to which the terms at all other descriptive levels can be reduced.

But this reductive credo also produced critical assessments and alternative proposals. A philosophical precursor of trends against a fundamental ontology is Quine's (1969) ontological relativity. Quine argued that if there is one ontology that fulfills a given descriptive theory, then there is more than one. It makes no sense to say what the objects of a theory are, beyond saying how to interpret or reinterpret that theory in another theory. Putnam (1981, 1987) later developed a related kind of ontological relativity, first called internal realism, later sometimes modified to pragmatic realism.

On the basis of these philosophical approaches, Atmanspacher and Kronz (1999) suggested how to apply Quine's ideas to concrete scientific descriptions, their relationships with one another, and with their referents. One and the same descriptive framework can be construed as either ontic or epistemic, depending on which other framework it is related to: bricks and tables will be regarded as ontic by an architect, but they will be considered highly epistemic from the perspective of a solid-state physicist.

Coupled with the implementation of relevance criteria due to contextual emergence (Atmanspacher 2016), the relativity of ontology must not be confused with dropping ontology altogether. The "tyranny of relativism" (as some have called it) can be avoided by identifying relevance criteria to distinguish proper context-specific descriptions from less proper ones. The resulting picture is more subtle and more flexible than an overly bold reductive fundamentalism, and yet it is more restrictive and specific than a patchwork of arbitrarily connected model fragments.

"----------

From: Mathias Brochhausen <mbroch...@gmail.com>

Date: Wed, Mar 28, 2018 at 2:15 AM

To: ontolo...@googlegroups.com

----------

From: Mike Bennett web client <mben...@hypercube.co.uk>

Date: Wed, Mar 28, 2018 at 7:50 AM

To: ontolo...@googlegroups.com

Hans,

Most of those things are covered by what John Searle calls 'social

constructs'. These are real things, even if they are not physical. They

are created by linguistic acts.

Separately, which is what I believe John is describing, are concepts of

things that need to be thought about whether or not they are in the real

world. A favorite example of mine is risk - you can't manage risk without

talking about events that mostly never happen.

Putting these side by side: An amount of money is a social construct, real

but not physical. A budget forecast is framed using the concept of an

amount of money, whether not not that amount is realized. Likewise a risk

assessment may identify the potential loss of an amount of money, or be

framed in terms of the concept of some legal exposure - itself a real

thing if it happens, but needing to be conceptualized whether or not it

does.

So these are distinct issues. Just not being physical is not the

determinant here.

Mike Bennett

----------

From: John F Sowa <so...@bestweb.net>

Date: Wed, Mar 28, 2018 at 8:03 AM

To: ontolo...@googlegroups.com

Cc: Doug Skuce <drs...@gmail.com>

Dear Matthias,

I apologize for doubting your knowledge of logic. But I was annoyed

by the word 'delusional' in the title of your paper and the suggestion

that the work of the best scientists and engineers is at the same level

as talk about mythical beasts.

Furthermore, I was responding to a note by Ravi, who was misled by

that title and some of the content. He asked how we can "separate

ontologies that pertain to known or real domains ... vs some illogical

non-plausible ... ontologies that might be purely imaginary."

In my response, I wanted to emphasize that the category "imaginary"

in your proposal includes all the R & D that he and other scientists

and engineers have been doing all their lives.

DL is a subset of First Order Logic. Hence, considerations of modal

logic are not relevant and the solutions that modal logic provides

to those problems are not accessible to those working with DL.

That is a critical issue that has many implications, for both

logic and ontology:

1. The words 'real' and 'imaginary' are closely related to the

terms 'actual' and 'possible' in modal logics. They raise

similar issues, which cannot be completely resolved in FOL

or any subset, such as DLs. Points #2, #3, and #4 show why.

2. Many DL experts, starting with Ron Brachman, have observed that

DLs have a modal effect when used as a T-Box in conjunction

with an A-Box (which may be any source of assertions, such as

a database or the WWW). The reason for this modal effect is

that the T-Box is assumed to have a higher priority or

entrenchment with respect to other sources of information.

This method has been successfully used for years.

3. Ontologies are often used in design stages where modal terms occur,

such as obligatory, mandatory, optional, required, prohibited....

In those cases, the same ontology should be used in the design

stage, where the modal terms are used, and in the finished product,

where everything is actual. Since nearly every product goes through

many stages of design and revision, constantly switching from one

ontology to another would cause confusion and introduce bugs.

4. Finally, I used the example of Kripke semantics. S4 and S5 are

two widely used versions of modal logic. S5 implies that every

world, real or possible, would have exactly the same ontology.

S4 implies that any possible world that is accessible from the

real world would have mostly the same ontology, but perhaps with

some updates or revisions.

In short, specifications in the design stage typically use modal

terms, and everything in a finished product is actual. Ideally,

the same ontology should be used in both stages.

I don't know whether Barry Smith approves of your proposal. I hope

not, but I fear that he might. In any case, Barry and I are scheduled

for a debate in the Ontology Symposium on May 1. This would be a good

topic to discuss.

----------

From: John F Sowa <so...@bestweb.net>

Date: Wed, Mar 28, 2018 at 8:19 AM

To: ontolo...@googlegroups.com

On 3/28/2018 10:50 AM, Mike Bennett web client wrote:

Most of those things are covered by what John Searle calls 'social

constructs'. These are real things, even if they are not physical.

They are created by linguistic acts.

I agree. But I'd add that other kinds of signs may be used instead

of or in conjunction with some "speech act", such as a promise.

For example, a handshake with a witness can be used as evidence

in a court of law.

For related issues, see "Signs, processes, and language games":

http://jfsowa.com/pubs/signproc.pdf

By the way, I had to delay my trip to San Diego by one day.

So I'll be able to call in for today's ontology summit. But

I may have to sign off early.

----------

From: Mike Bennett web client <mben...@hypercube.co.uk>

Date: Wed, Mar 28, 2018 at 9:07 AM

To: ontolo...@googlegroups.com

Very good point. I avoided the term 'speech act' in preference for

'linguistic act' per Barry Smith but you are right there are body language

symbols that might not obviously come under that heading.

Mike

----------

From: <hpo...@verizon.net>

Date: Wed, Mar 28, 2018 at 9:20 AM

To: ontolo...@googlegroups.com

John,

I agree that there are signs and marks that are physical manifestations of these types of conceptual/social/political entities. However, those physical manifestations are typically not physically associated with the physical entities to which they refer/signify. The association is only knowable to those who have previously been educated/apprised of the mark and what it signifies. If you lack that knowledge, no physical sensor will inform you of the existence of such entities. One may try to infer their existence by observing behaviors of others who are suspected of having such knowledge, but this is a probabilistic process with usually significant error margins.

BTW, I often harp on this point because of past dealings with people in domains where such knowledge is hard to come by and yet they tend to expect to obtain perfect knowledge about such entities from physical sensors (e.g., radars, infrared, sonic, radio emissions, etc.). I also often highlight the Internet revolution as making more of such signs and marks broadly accessible, but not necessarily making the marks understandable to those who haven't been clued in to their significance. In part, this is due to a lack of explicit context representation associated with such Internet-accessible marks.

Hans

-----Original Message-----

From: ontolo...@googlegroups.com <ontolog-forum@googlegroups.com> On Behalf Of John F Sowa

----------

From: Michael DeBellis <mdebe...@gmail.com>

Date: Wed, Mar 28, 2018 at 9:44 AM

To: ontolog-forum <ontolo...@googlegroups.com>

----------

From: John F Sowa <so...@bestweb.net>

Date: Wed, Mar 28, 2018 at 1:17 PM

To: ontolo...@googlegroups.com

Cc: Doug Skuce <drs...@gmail.com>

Hans and Michael,

HP

I agree that there are signs and marks that are physical manifestations

of these types of conceptual/social/political entities. However, those

physical manifestations are typically not physically associated with

the physical entities to which they refer/signify.

That is why you need Peirce's complete semiotic system.

An icon resembles its referent in some way.

An index points to it in some way.

And a symbol refers to something by convention.

As Peirce said, symbols evolve from icons and other symbols.

That's true of all alphabets and characters in the world.

The letter M came from the Egyptian hieroglyph for water (waves).

From that to simplified Egyptian to Phoenician to Greek to Latin.

See "Signs and Reality": http://jfsowa.com/pubs/signs.pdf

HP

yet they tend to expect to obtain perfect knowledge...

from physical sensors (e.g., radars, infrared, sonic, radio

emissions, etc.).

Physical measurements can never be perfect, and observations

are always fallible. That gets into epistemology (study of

how and what we can know) as opposed to ontology (study of

what exists). Since epistemology can never be perfect,

every ontology is at best a useful approximation for some

purpose or range of purposes.

MDB

this distinction between "real" and "not real" is not some well

defined rigorous notion. I.e., it's not something we should expect

that logic could inherently distinguish. Like many things in human

language it's highly context dependent.

That opens up many more cans of worms. Three more articles

about related issues:

Five questions on epistemic logic:

http://jfsowa.com/pubs/5qelogic.pdf

What is the source of fuzziness?

http://jfsowa.com/pubs/fuzzy.pdf

The challenge of knowledge soup:

http://jfsowa.com/pubs/challenge.pdf

Brief summary: logic, epistemology, ontology, semiotics, and

linguistics are all involved (or entangled) in these issues.

You can't expect to get a complete solution from any one of them.

If you try to mash them all in one package, you get knowledge soup.

----------

From: Mike <rega...@gmail.com>

Date: Wed, Mar 28, 2018 at 1:38 PM

To: ontolo...@googlegroups.com

I do believe that, as cast in this discussion, the distinction between “real” and “imaginary” may not be very useful, except to strict conceptual realists or their opponents trying to create a cause célèbre. I believe this for reasons other than considerations of logical modality, and more so in appreciation of Searle’s view of social reality. Inject humans and you get two planes of reality: the physical world; and the world as humans know it. Humans immediately construct a myriad of concepts to organize and explain the other plane – the physical world as they believe it exists. This approximation of physical reality including, of course, sentient humans and their enterprises relies on a construction and renewable consensus of the meaning of instructive concepts like center-of, residence, contract, country, risk, regret, friend, money, bingo, inertia and atom. Some formal agreement of meaning can be shared across a population, but what is being shared is ultimately a cognitive phenomenon being experienced in the brain of each individual so informed. This individual experience of rather abstract concepts is presumably not exactly the same for everyone or at every point in one’s lifetime. I will go further and contend that this rather fuzzy experience arises not just for the constructs of social reality but for each notion of everything in the physical world as well. The individual experience of any conceptualization must be idiosyncratic to each person, and the central tendency of those experiences is what constitutes the consensual meaning of being a particular thing. Gotten this far, it seems that it is this mental occurrence that is “imaginary” as it is uniquely private to the individual and unavailable to others except by communicating a shareable approximation expressed in verbal, pictorial or mathematical/logical terms. In other words, there is real and there is what individual humans imagine to be real.

Mike

From: ontolo...@googlegroups.com [mailto:ontolog-forum@googlegroups.com] On Behalf Of Michael DeBellis

Sent: Wednesday, March 28, 2018 12:44 PM

To: ontolog-forum

Subject: Re: [ontolog-forum] Higgs bosons, Mars missions, and unicorn delusions

----------

From: <hpo...@verizon.net>

Date: Wed, Mar 28, 2018 at 2:49 PM

To: ontolo...@googlegroups.com

John,

I think you are missing my point. The issue is not the accuracy of physical measurements of some physical entity in space-time. The issue is determining whether said physical entity is indeed a member of some larger conceptual entity - without the benefit of access to human-generated information sources - i.e., the signs and marks you mentioned in your email. For example, how would I know which people in some public assembly are members of the faculty of some university, simply by taking physical measurements?

Sure, they might be wearing some sort of externally visible ID, or maybe I could do 3-D tomography and read the ID cards in their wallet or purse (assuming they are carrying one on their person). But even that requires me to have some kind of knowledge about what types of IDs individual faculty members of that university possess. Or I could observe that certain individuals in the crowd eventually find their way to a building that I happen to know is a classroom for said university, and if I could see inside that classroom and detect the individual is at some sort of lectern position, I might infer that the person is a faculty member. But I could also be quite wrong about that, regardless of the accuracy of my physical observations - or the observations of the students in the classroom. I could also try to do something like facial recognition - but that would require access to some "authoritative" source of facial images of that university's faculty, not just physical measurement of facial images. Maybe the tweed jacket and elbow patches would be a dead giveaway??

The trend to bar code, RF ID, and GPS location enable just about everything is in fact an attempt to address this very prevalent issue in the government and business IT world. But the general problem I am referring to still exists and is very problematic in domains where the physical entities making up the larger composite/conceptual entities either don't have any externally detectable marks signifying their membership relationship for pragmatic reasons, or deliberately don't want that relationship to be detectable by others for privacy or nefarious reasons (as in your Mafia example).

Hans

-----Original Message-----

From: ontolo...@googlegroups.com <ontolog-forum@googlegroups.com> On Behalf Of John F Sowa

----------

From: John F Sowa <so...@bestweb.net>

Date: Wed, Mar 28, 2018 at 6:56 PM

To: ontolo...@googlegroups.com

Mathias, Hans, Michael, Mike, and Ravi,

I reread the paper with the above title, and I have to admit that

the authors went to a huge amount of work to make their system work.

I admit that it's possible to represent what they want to represent

and to make appropriate inferences from it.

It is really a tour de force. But I also believe that they could have

made their own lives easier and spared their readers a great deal of

effort if they had designed an ontology along the following lines:

1. OWL is very complex and quirky. Common Logic is much simpler,

and it offers a more systematic set of primitives with which to

specify the categories in the ontology.

2. With those categories defined in CL, they would have a framework

with which to specify equivalents of everything they need to specify

for their applications. And they could do so without going outside

the expressive power of OWL DL.

3. But the simpler and more expressive semantics of Common Logic allows

them to define a clean, elegant ontology. There is no need to worry

whether some universals (AKA functions and relations) do or do not

happen to have instances in the actual world or some possible

world. The presence of instances is a contingent issue that is

independent of the definitions.

For a quick overview of such an ontology, consider Common Logic

(or something like it) as the base logic. The following paper about

Peirce's semiotic discusses ways to use such a logic to define the

primitives: http://jfsowa.com/pubs/signs.pdf .

When the primitives are defined in CL, they can be used in OWL DL

to specify everything needed for the paper with the above title.

And Hans, Michael, Mike, and Ravi, I mostly agree with your points.

But I have to fly to San Diego tomorrow morning.

Until next week,

----------

From: Chris Mungall <cjmu...@lbl.gov>

Date: Wed, Mar 28, 2018 at 11:32 PM

To: ontolo...@googlegroups.com

Hi Matthias,

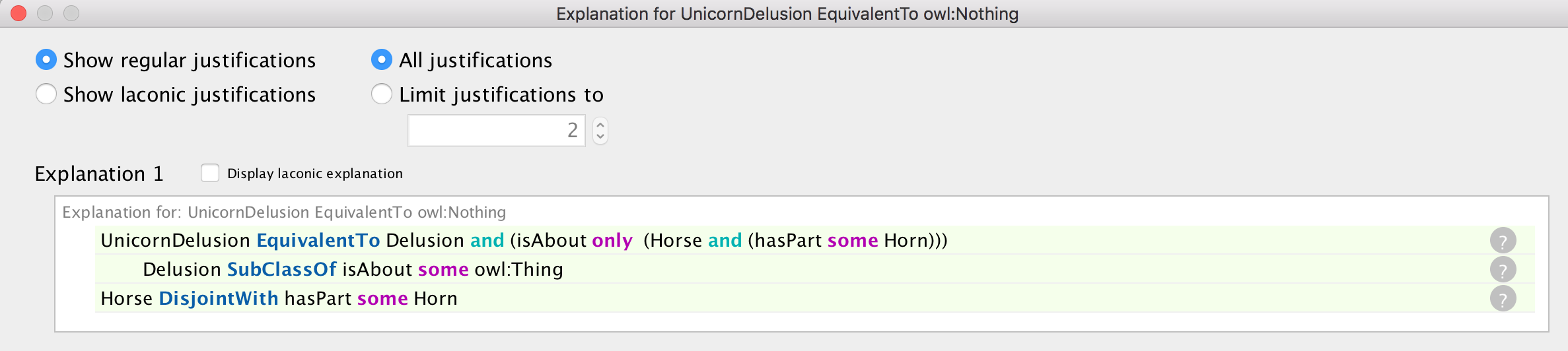

Interesting paper, but I'm confused about equation 12. I encoded this in the attached ontology. I also added an axiom to state that delusions must be about something, otherwise equations 11 and 12 don't carry any force (a delusion that is not about anything would be equivalent to a unicorn delusion, since it's not about anything that isn't a unicorn).

Using this ontology, if I state that horned horses don't exist, then unicorn delusions become unsatisfiable. I don't think that's your intent or the intent of even the kind of weak-tea realism I subscribe to, in which the world of our scientific ontologies are buffered from any kind of phantasmagoric ontology (which may not even be logically consistent). When you try and put these things on the same footing, axioms and unsatisfiability 'leaks' from one 'world' to another.

This is the ontology in manchester syntax:

Prefix: : <http://unicorn.org/>

Ontology: <http://unicorn.org>

ObjectProperty: isAbout

ObjectProperty: hasPart

Class: Horn

Class: Delusion SubClassOf: isAbout some owl:Thing

Class: UnicornDelusion EquivalentTo: Delusion and isAbout only (Horse and hasPart some Horn)

Class: Horse DisjointWith: hasPart some Horn

This is the explanation of unsatisfiability in HermiT:

Note that it gets worse if you add instances, e.g. my own delusion about my pink unicorn:

Individual: MyUnicornDelusion Types: Delusion and isAbout only (Horse and hasPart some Horn)

This results in the whole ontology being inconsistent. i.e. the only consistent worlds are ones in which our delusions are about real things.

Apologies if I'm missing something, but was this your intent?

FWIW I'm not sure there is a use case for reasoning about fantasy entities. The most straightforward thing is to keep direct representations of unicorns and imaginary homeopathic processes out of scientific ontologies, and to have a lightweight minimally axiomatized ontologies of delusions, fiction etc if they are required (e.g. for a psychiatric ontology).

I enjoyed the paper, though I'm glad the bio-ontology community has moved on from unicorns and onto more pragmatic concerns.

“Reasonable people adapt themselves to the world.

Unreasonable people attempt to adapt the world to themselves.

All progress, therefore, depends on unreasonable people.”

- George Bernard Shaw