Who's afraid of the big, bad Jevons?

Zachary Semke

“Increasing aggregate fuel efficiency makes fuel effectively cheaper and more available, which ultimately increases, rather than decreases fuel consumption. At least that's what I'm pondering these days. Hence my thought that energy efficiency and reduced carbon emissions are separate issues, and that the solution to global warming lies elsewhere.”

“The key to understanding Jevons is that processes, products, and activities where energy is a very high part of the cost – in this country, a few metals, a few chemicals, air travel – are the only ones whose variable cost is very sensitive to energy. That’s it.”

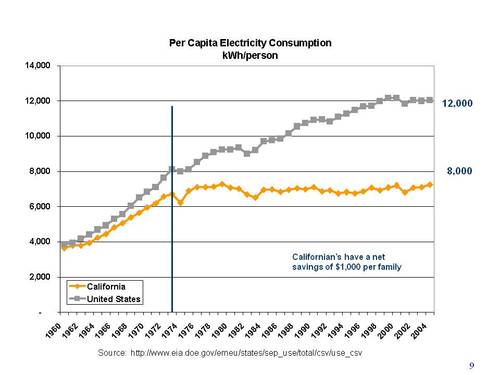

If Jevons applied here, California’s efficiency gains would have driven GREATER per capita consumption. Instead, it has SLASHED per capita consumption. Maybe a smart, Jevons-believing economist could unpack the data and prove Jevons lurked here somewhere, perhaps hidden by other variables. But show us the data.

- 52% of Americans now say they are worried about climate change.

- While any carbon tax initiative will need to battle entrenched dirty energy interests, plenty of one-percenters are freaked out about climate change and have no vested interest in dirty energy...Silicon Valley anyone?

- The same potential for a “black swan” event that fuels nightmares of wholesale ecosystem collapse also applies to positive change and paradigm shifts. Examples: fall of Soviet Union, the imminent solar power tipping point, election of a black President, acceptance of gay marriage, etc.

Bronwyn Barry

--

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "Passive House Northwest" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to PassiveHouseN...@googlegroups.com.

For more options, visit https://groups.google.com/d/optout.

Director - One Sky Homes

Zachary Semke

Bronwyn Barry

Zack Semke

Sent from my iPhone

<fridges.jpg>

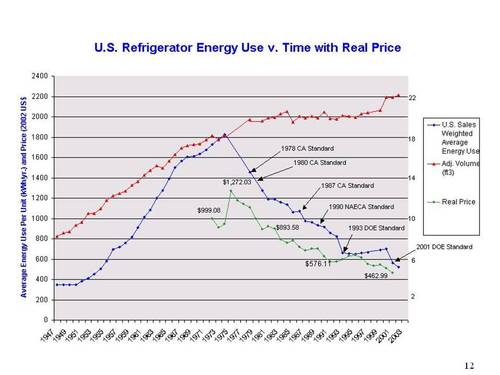

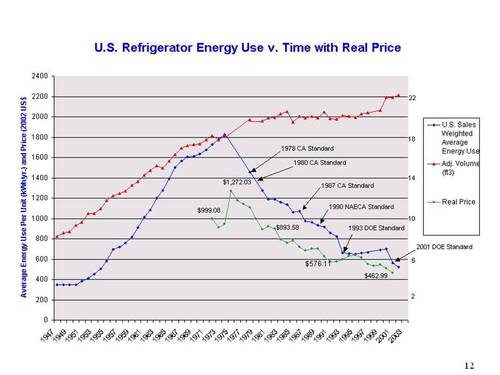

It shows that expansion of fridge size (the red line) SLOWED significantly just as energy efficiency began to improve after 1972. If Jevons applied to fridges, we should have seen a big spike in fridge size after 1972. That didn't happen so there's no proof of Jevons here. Likely the opposite.I suspect that the same is true of LEDs. Surely there’s a rebound effect as folks feel freer to use their lights. But I highly doubt that it rises to the level of the Jevons Paradox where LED efficiency actually INCREASES electricity use for lighting. It certainly hasn’t in my house – and we are no saints. And those pictures of LEDs on building exteriors in Asia? That sort of exterior lighting has been going on in Asia for decades – just look at a picture of Tokyo in the 80s, or fire up a copy of Blade Runner again. Lighting efficiency did not create that phenomenon, and likely makes a fairly wasteful practice much more efficient. Am I wrong? Let’s see some numbers.The reality is that even one of the most prominent champions of the Jevons Paradox (David Owen, author of “The Efficiency Dilemma”) admits that most economists agree that the Jevons Paradox doesn’t apply to our world today. He quotes Stanford University’s Lee Schipper:

“The key to understanding Jevons is that processes, products, and activities where energy is a very high part of the cost – in this country, a few metals, a few chemicals, air travel – are the only ones whose variable cost is very sensitive to energy. That’s it.”

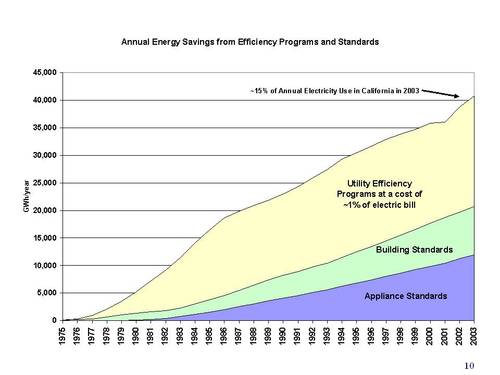

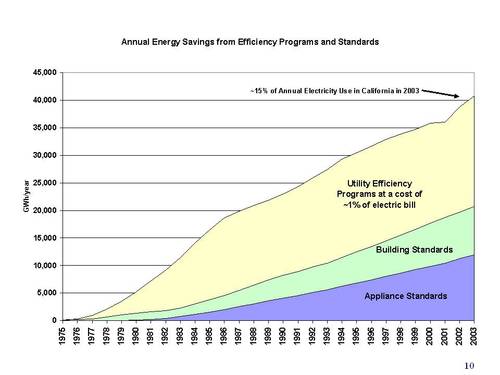

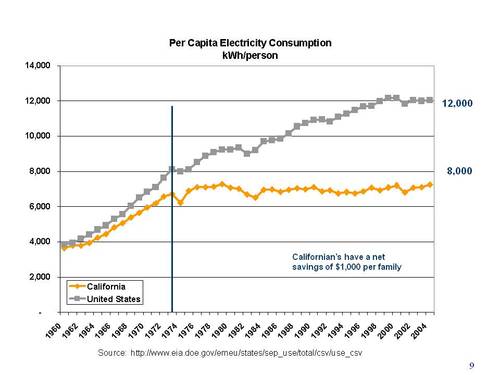

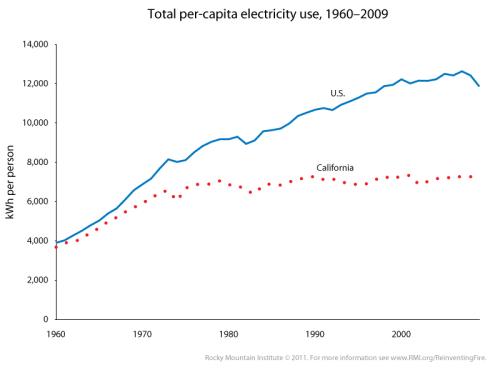

Unfortunately, Owen goes on to ignore Schipper and weave the whole refrigerator yarn again. No data support provided.3. We shouldn’t conflate the Affluence Effect with the Jevons Paradox.Lacking numbers-based evidence of Jevons at the microeconomic scale, Owens and other Jevons champions pivot to a larger, macroeconomic version: energy efficiency makes our society richer, which increases energy consumption.But even this assertion is challenged by the numbers. Take a look at these two graphs, again from Goldstein at NRDC:California energy efficiency measures

<cal-efficiency.jpg>

California per capita electricity consumption

<cal-consumption.jpg>

Albert Rooks

Hayden Robinson

Okay, okay, supporting data:

For a peer-reviewed summary of econometric publications on the topic, see:

The Rebound Effect: an assessment of the evidence for economy-wide energy savings from improved energy efficiency. UK Energy Research Centre, 2007, which concludes:

The general conclusion of this assessment is that rebound effects need be taken more seriously by analysts and policymakers than has hitherto been the case.

My apologies if I helped get the conversation off track. I'd like to back up for a moment and remember where we're going, and how we got here.

A criticism of Passive House's has been that its focus on passive systems is uneconomical; it's been asserted that money would be better spent on PV. Unlike Passive House, PHIUS+ 15 gives credit for PV, and in the PHNW6 presentation, Why Passive House?, in addition to conventional passive strategies, PV was added.

Conservation vs generation is a question that I grapple with personally. I live in a rather charming, 105-year-old house. One evening I walked around it, with one of the PHIUS co-directors, pointed out the architectural damage that would accompany retrofitting it to the Passive House standard, and confessed that I could not bring myself to do it. (He said he wouldn't either.) I can still live with myself, but I'm left torn, wanting to do the right thing, and wishing there were an alternative. PV comes to mind - wouldn't it offset some of the waste from my non-Passive House? After all, isn't a kilowatt hour earned, a kilowatt hour saved? Make sense, right? But, as my, economist friend says: Makes sense, but is it true?

I've not found the answer. At the end of, Why Passive House?, I presented my conservation/generation dilemma. In other words, how confident can I be that, when my PV system generates 2,000 kWh of electricity, a ton of coal, or a barrel of oil, will stay in the ground forever? With Lloyd Alter's help on remembering the name, Zack pointed me to the Jevons effect - I'd never heard of it. Of course, Jevons came up again in Lloyd's and Steve Hallet's keynotes.

Jevons' observation about the relationship between consumption and efficiency kinda, sorta related to my question about the interchangeability of conservation and production, and kinda, sorta didn't. But it raised other questions, sounded interesting, and made sense. But, was it true? I went home and turned to the internet. My first impression was that, economics being what it is, much of the blog-level discussion out there was agenda influenced, and that commentary and conclusions seemed to align with the world view of the writers and publications: there are those that are sure it's applicable, and those that are sure it isn't, and it's not always clear that facts matter. I read Who's afraid of the big, bad Jevons? and came away unconvinced. I've noticed that a theme of anti-Jevons commentary is to pick a microeconomic example, ignore macroeconomic context, and exclaim that they've proved something; a lot of it is plain silly, the intellectual equivalent of pointing out that water-efficient toilets, don't lead to increased toilet use, then asserting that none of the water the toilets save will be used to fill swimming pools, water golf courses, or grow almonds at 5 gallons each, and go on to assert that water saved will stay in the aquifer forever.

Jevons, and his 21st century peers, raise worthwhile questions. And sometimes we should be willing to ask ourselves what the heck we are doing, and why? Doesn't mean we should become nihilists, or stop designing, building, and living in a manner that is consistent with the kind of world we want to live in. After all, solutions to the problems we face are all about human choices and behavior.

There is a lot talk these days about PV-fueled, primary-energy reduction as an equivalent alternative to building performance. It's not clear to me that it either makes sense, or is true. It seems worth figuring that out before encouraging a wholesale shift in that direction.

Zack Semke

Sent from my iPhone

Hayden Robinson

Zack,

You're the one that suggested looking at Jevons . If you've decided he isn't helpful, fine. But changing the subject, over and over, doesn't answer the question:

How confident can I be that, when my PV system generates 2,000 kWh of electricity, a ton of coal, or a barrel of oil, will stay in the ground forever?

Zachary Semke

Hi PHnw-ers,

I wouldn’t blame you if you’re tuning out on this discussion about Jevons by now. I’m going to respond to Hayden below, so if you’re a glutton for punishment you can avail yourself of more...

But before I do, I wanted to quickly encapsulate why I feel that the axiom “energy efficiency causes greater consumption of energy, not less” isn’t good for us (aside from the fact that it’s usually wrong):

- It robs the practitioner of perhaps the biggest motivation of his/her work: helping to make a contribution (however small) to the climate solution.

- It robs “the movement” of a powerful means of attracting new champions.

- It robs the client of a powerful motivation for building a Passivhaus or passive building. (Health and happiness are important selling points, but every single one of our Passive House clients has expressed concern for climate as a driving part of their decision to pursue a passive building.)

- It robs us of a powerful argument for including Passivhaus/passive building in building code or incentive programs aimed at reaching things like Climate Action Plans.

- It plays into the hands of those who prefer the status quo.

For all these reasons, we’d be crazy to assume that the Jevons Paradox applies to the world of Passivhaus/passive building without incontrovertible evidence to prove it is so.

By definition, the Jevons Paradox says that energy efficiency efforts, like Passivhaus and passive building, are counterproductive. That’s why the Paradox is also called “backfire”. Rebound effects, which are widely accepted as being a normal part of doing energy efficiency work, are not the Jevons Paradox (unless the rebound is greater than 100%, which appears to be very rare).

If the Jevons Paradox tells us “what I’m doing to address energy consumption is counterproductive,” a rebound effect tells us “what I’m doing to address energy consumption is less than 100% effective.”

Okay that is all – thanks for humoring me. Now onto my reply to Hayden:

Hi Hayden,

I confess to being confused by your statement that I’ve changed the subject. I started here and here is where I remain:

Hayden, in your last message you included this footnote:

“Increasing aggregate fuel efficiency makes fuel effectively cheaper and more available, which ultimately increases, rather than decreases fuel consumption. At least that's what I'm pondering these days. Hence my thought that energy efficiency and reduced carbon emissions are separate issues, and that the solution to global warming lies elsewhere.”

To recap, I think these two ideas are wrong:

- Increasing fuel efficiency (aggregate or no) increases fuel consumption (aka the Jevons Paradox). (I’ve only seen evidence that the Jevons Paradox (meaning BACKFIRE, not rebound) applies in very few outlier cases, and I therefore believe it is a red herring.)

- Energy efficiency and carbon emissions are separate issues and that the solution to global warming lies elsewhere.

Have you changed your mind on these two points? If so then maybe there's no disagreement between us.

My argument, as you’ll recall, is this:

- Economists universally agree that a small rebound effect does exist.

- (My Prius example mentioned a 6-8% rebound. This Energy Journal article estimates rebound at 10-30% for residential and transportation sectors, and 0-20% for industries – meaning that energy efficiency measures are 70-100% effective.)

- You gotta prove it with data or you’re just storytelling.

- Energy efficiency did not cause fridge size to increase.

- We shouldn’t conflate the Affluence Effect with the Jevons Paradox.

- Even the macroeconomic argument for Jevons doesn’t appear supported by the numbers.

- Even if the Jevons Paradox does have an effect at the macroeconomic scale, environmental economists point out that a simple green tax (like a carbon tax) would wipe out the effect.

So! On to the articles you cited as evidence for Jevons:

The peer-reviewed article from the UK Energy Research Centre is excellent, and supports points 1, 2, and 4 outlined above (the “Affluence Effect” isn’t really addressed by the paper):

1. Rebound effect is likely between 10% and 30%. (Page vi)

2. Jevons Paradox (referred to here as the “K-B Postulate”) remains unverified: “This provocative claim would have serious implications for energy and climate policy if it were correct. However, the theoretical arguments in favour of the postulate rely upon stylised models that have a number of limitations, such as the assumption that economic resources are allocated efficiently. Similarly, the empirical evidence for the postulate is indirect, suggestive and ambiguous. Since a number of flaws have been found with both the theoretical and empirical evidence, the K-B ‘hypothesis’ cannot be considered to have been verified.” (Page vii)

4. Carbon/energy pricing implemented in tandem with energy efficiency measures can reduce rebound effects. (Page ix)

My point, here, is that the UK Energy Research Centre article proves my point. While there is a small (but significant-and-not-to-be-ignored) rebound effect, there’s no proof that the Jevons Paradox is at work. And in any case, carbon/energy pricing is an effective tool to address rebound (and by extension any possible yet-to-be-verified Jevons Paradox.)

I’m highly skeptical of the other article you shared, as it’s an unpublished paper (“From the SelectedWorks of Harry D. Saunders”) produced by a Senior Fellow at the controversial “Breakthrough Institute.” If there ever were an academic with a point to prove and axe to grind, it would be an economist working at BTI – a biased source to be sure. These guys are pro-nukes, pro-natural gas (arguing for a “doubling down” on natural gas production), pro-Jevons Paradox (its leading cheerleader, really), and anti-carbon tax.

SourceWatch, a project of the Center for Media and Democracy cites this critique of BTI:

"The Breakthrough people and their allies, among whom one must include Lomborg and Pielke Jr. at this point... are not asking for the technologically impossible. They are asking merely for the technologically possible at an economically impossible cheap price." "This disinformation campaign is almost entirely driven by fossil fuel companies and conservative media, politicians and think tanks. It is also advanced by the Breakthrough Institute and its president, Michael Shellenberger. His central myth -- a science fiction fantasy, really -- is that it would be possible to sharply reduce emissions without raising the cost of carbon pollution."

http://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php/Talk:Breakthrough_Institute

Here are some choice articles about BTI:

- “Don’t believe the fossil-fuel lies: joining oil companies and conservatives, the Breakthrough Institute says we can reduce emissions without raising the cost of carbon pollution. It’s a fantasy.” Salon Magazine

- “Breakthrough Institute gets it wrong on climate economics – again.” Grist

- “Breakthrough Institute’s Pielke in a Pickle.” Climate Investigations Center

- “The Breakthrough Institute: Why the hot air?” Clean Technica

- “Rebound effect: The Breakthrough Institute’s attack on clean energy backfires.” Climate Progress

- “Breakthrough Institute fraudulently paints the IPCC Report as a pro-nuclear document!” Nuclear News

- “The Latest Blast of Disinformation From the Pseudo-Contrarians” Counter Punch

You’ll notice a clear political pattern here: the progressive media (Salon for example), the environmental media (Grist for example), and climate activists believe that the Breakthrough Institute is engaged in a disinformation campaign.

And, ultimately, Jevons boils down more to ideology than anything, given that so far there’s either no evidence for meaningful applications of the Paradox, or evidence based on models devised by economists at BTI, a “research body” with an agenda.

I appreciate and respect your passion about the differences between Passivhaus and PHIUS+ 2015. I hope you are cautious about employing Jevons in making your case, however. It's a dangerous game, in my view; too easy to play into the hands of folks whose agenda is anathema to most of us in this Passiv(e) community: achieving transformational energy conservation and progress toward a climate solution.

- Z

P.S. In your latest email you asked me this question: “How confident can I be that, when my PV system generates 2,000 kWh of electricity, a ton of coal, or a barrel of oil, will stay in the ground forever?” My answer is: “not at all confident.” We may indeed drive right off the cliff and burn everything in the ground. No guarantees. But I don’t accept that as fait accompli. If I thought the Jevons Paradox applied to the world of high performance building or that macroeconomic rebound effects could not be addressed with tools like a carbon tax then maybe I’d accept that (dark) fate as inevitable. But I believe there’s reason for hope.

To: Passive...@googlegroups.com

Subject: Re: Who's afraid of the big, bad Jevons?

Hi PHnw-ers,

I wouldn't blame you if you're tuning out on this discussion about Jevons by now. I'm going to respond to Hayden below, so if you're a glutton for punishment you can avail yourself of more...

But before I do, I wanted to quickly encapsulate why I feel that the axiom "energy efficiency causes greater consumption of energy, not less" isn't good for us (aside from the fact that it's usually wrong):

- It robs the practitioner of perhaps the biggest motivation of his/her work: helping to make a contribution (however small) to the climate solution.

- It robs "the movement" of a powerful means of attracting new champions.

- It robs the client of a powerful motivation for building a Passivhaus or passive building. (Health and happiness are important selling points, but every single one of our Passive House clients has expressed concern for climate as a driving part of their decision to pursue a passive building.)

- It robs us of a powerful argument for including Passivhaus/passive building in building code or incentive programs aimed at reaching things like Climate Action Plans.

- It plays into the hands of those who prefer the status quo.

For all these reasons, we'd be crazy to assume that the Jevons Paradox applies to the world of Passivhaus/passive building without incontrovertible evidence to prove it is so.

By definition, the Jevons Paradox says that energy efficiency efforts, like Passivhaus and passive building, are counterproductive. That's why the Paradox is also called "backfire". Rebound effects, which are widely accepted as being a normal part of doing energy efficiency work, are not the Jevons Paradox (unless the rebound is greater than 100%, which appears to be very rare).

If the Jevons Paradox tells us "what I'm doing to address energy consumption is counterproductive," a rebound effect tells us "what I'm doing to address energy consumption is less than 100% effective."

Okay that is all - thanks for humoring me. Now onto my reply to Hayden:

Hi Hayden,

I confess to being confused by your statement that I've changed the subject. I started here and here is where I remain:

Hayden, in your last message you included this footnote:

"Increasing aggregate fuel efficiency makes fuel effectively cheaper and more available, which ultimately increases, rather than decreases fuel consumption. At least that's what I'm pondering these days. Hence my thought that energy efficiency and reduced carbon emissions are separate issues, and that the solution to global warming lies elsewhere."

To recap, I think these two ideas are wrong:

- Increasing fuel efficiency (aggregate or no) increases fuel consumption (aka the Jevons Paradox). (I've only seen evidence that the Jevons Paradox (meaning BACKFIRE, not rebound) applies in very few outlier cases, and I therefore believe it is a red herring.)

- Energy efficiency and carbon emissions are separate issues and that the solution to global warming lies elsewhere.

Have you changed your mind on these two points? If so then maybe there's no disagreement between us.

My argument, as you'll recall, is this:

- Economists universally agree that a small rebound effect does exist.

- (My Prius example mentioned a 6-8% rebound. This Energy Journal article estimates rebound at 10-30% for residential and transportation sectors, and 0-20% for industries - meaning that energy efficiency measures are 70-100% effective.)

- You gotta prove it with data or you're just storytelling.

Energy efficiency did not cause fridge size to increase. - We shouldn't conflate the Affluence Effect with the Jevons Paradox.

Even the macroeconomic argument for Jevons doesn't appear supported by the numbers. - Even if the Jevons Paradox does have an effect at the macroeconomic scale, environmental economists point out that a simple green tax (like a carbon tax) would wipe out the effect.

So! On to the articles you cited as evidence for Jevons:

The peer-reviewed article from the UK Energy Research Centre is excellent, and supports points 1, 2, and 4 outlined above (the "Affluence Effect" isn't really addressed by the paper):

1. Rebound effect is likely between 10% and 30%. (Page vi)

2. Jevons Paradox (referred to here as the "K-B Postulate") remains unverified: "This provocative claim would have serious implications for energy and climate policy if it were correct. However, the theoretical arguments in favour of the postulate rely upon stylised models that have a number of limitations, such as the assumption that economic resources are allocated efficiently. Similarly, the empirical evidence for the postulate is indirect, suggestive and ambiguous. Since a number of flaws have been found with both the theoretical and empirical evidence, the K-B 'hypothesis' cannot be considered to have been verified." (Page vii)

4. Carbon/energy pricing implemented in tandem with energy efficiency measures can reduce rebound effects. (Page ix)

My point, here, is that the UK Energy Research Centre article proves my point. While there is a small (but significant-and-not-to-be-ignored) rebound effect, there's no proof that the Jevons Paradox is at work. And in any case, carbon/energy pricing is an effective tool to address rebound (and by extension any possible yet-to-be-verified Jevons Paradox.)

I'm highly skeptical of the other article you shared, as it's an unpublished paper ("From the SelectedWorks of Harry D. Saunders") produced by a Senior Fellow at the controversial "Breakthrough Institute." If there ever were an academic with a point to prove and axe to grind, it would be an economist working at BTI - a biased source to be sure. These guys are pro-nukes, pro-natural gas (arguing for a "doubling down" on natural gas production), pro-Jevons Paradox (its leading cheerleader, really), and anti-carbon tax.

SourceWatch, a project of the Center for Media and Democracy cites this critique of BTI:

"The Breakthrough people and their allies, among whom one must include Lomborg and Pielke Jr. at this point... are not asking for the technologically impossible. They are asking merely for the technologically possible at an economically impossible cheap price." "This disinformation campaign is almost entirely driven by fossil fuel companies and conservative media, politicians and think tanks. It is also advanced by the Breakthrough Institute and its president, Michael Shellenberger. His central myth -- a science fiction fantasy, really -- is that it would be possible to sharply reduce emissions without raising the cost of carbon pollution."

http://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php/Talk:Breakthrough_Institute

Here are some choice articles about BTI:

(Apologies for the length of this - I tried to keep it as brief as possible...the reason for all my words?: I'm frankly fairly alarmed by the traction that Jevons seemed to get with our community a couple weeks ago. As you'll see below, I think the Jevons Paradox is a red herring. To the degree that it causes us to conclude that our efforts are unrelated to reducing carbon emissions, it is also counterproductive.)

"Why I think the Jevons Paradox is hooey, and you should, too."

-OR-

"Passivhaus and passive building DO address global warming."

(For folks new to Jevons...) Back in 1865, English economist WS Jevons observed that a new, more efficient steam engine was actually driving increased consumption of coal rather than the expected decreased consumption. The reason: because the new engines used less coal, the price of producing a unit of work with coal dropped, thereby increasing demand for coal. Hence the Jevons Paradox: "Increased efficiency causes greater consumption of a resource, not less."

Now, in our world of super-efficient construction, that's a pretty shitty message to hear, to put it baldly. If efficiency actually causes consumption, then what's the point of what we're doing? Yeah, maybe we're delivering health and comfort to occupants. And maybe these buildings are resilient places to set up survivalist camps to weather the Apocalypse. But, Jevons, you're telling me that all my green building good intentions are actually going to hasten climate change??

Wow, what a huge bummer.

And so counter-intuitive. (Suspiciously so.)

What I am uncovering as I delve into the Jevons Paradox, and how an 1865 paper may or may not apply to our world today, is that...

1. Economists universally agree that a small "rebound" effect does exist.

For example, if I save $100 on gas driving my Prius, in theory I will increase my overall consumption by about $100. Some proportion of that consumption will go to things that burn energy (estimated at 6-8%, the proportion of our economy made up of primary energy). So of the $100 in energy burning that my Prius prevented, I'll be spending about $6-8 on other energy burning (more miles on my Prius, consumer goods that take energy to produce, etc.) On balance, the efficiency of my Prius saved $92-94 in energy consumption ($100 minus $6-8). Not bad.

That $6-8 is the rebound. But it is not proof of the Jevons Paradox. Remember, Jevons says efficiency causes MORE consumption than would have otherwise occurred. So, given that my 50mpg Prius is more than twice as fuel efficient than the average 23.6 mpg US car, my car's efficiency would have to cause me to more than double my vehicle miles traveled to prove Jevons right. That's crazy talk. Yes, there's a rebound effect. But it's tiny compared to the efficiency gains. (Don't get me wrong...Priuses are not going to save the world...)

2. You gotta prove it with data or you're just storytelling.

At PHnw6 we were shown pictures of double-wide fridges and LEDs on buildings and told stories about how energy efficiency and affluence and profligate consumption are leading us in the wrong direction. It was compelling stuff. I especially liked Lloyd's cautions about the dangers of being seduced by technology at the expense of nailing the fundamentals of passive building. But the conversation about the Jevons Paradox was about pictures and narrative, not numbers. We didn't see data to support the causal (or even correlational) claims. And the only way I'm going to accept a notion as counterintuitive and, frankly, show-stopping, as Jevons is if I see some real proof that it applies to our world.

Let's look at the fridges. First, does anyone actually believe that people are buying double-wide fridges now because they are energy efficient? (If Jevons applies to fridge size, then energy efficiency CAUSES increases in fridge size.) A far more likely driver of double-wides is affluence and the big kitchens that wealth makes possible. But let's look at the data, this from David Goldstein of NRDC:

<fridges.jpg>

?

It shows that expansion of fridge size (the red line) SLOWED significantly just as energy efficiency began to improve after 1972. If Jevons applied to fridges, we should have seen a big spike in fridge size after 1972. That didn't happen so there's no proof of Jevons here. Likely the opposite.

I suspect that the same is true of LEDs. Surely there's a rebound effect as folks feel freer to use their lights. But I highly doubt that it rises to the level of the Jevons Paradox where LED efficiency actually INCREASES electricity use for lighting. It certainly hasn't in my house - and we are no saints. And those pictures of LEDs on building exteriors in Asia? That sort of exterior lighting has been going on in Asia for decades - just look at a picture of Tokyo in the 80s, or fire up a copy of Blade Runner again. Lighting efficiency did not create that phenomenon, and likely makes a fairly wasteful practice much more efficient. Am I wrong? Let's see some numbers.

The reality is that even one of the most prominent champions of the Jevons Paradox (David Owen, author of "The Efficiency Dilemma") admits that most economists agree that the Jevons Paradox doesn't apply to our world today. He quotes Stanford University's Lee Schipper:

"The key to understanding Jevons is that processes, products, and activities where energy is a very high part of the cost - in this country, a few metals, a few chemicals, air travel - are the only ones whose variable cost is very sensitive to energy. That's it."

Unfortunately, Owen goes on to ignore Schipper and weave the whole refrigerator yarn again. No data support provided.

3. We shouldn't conflate the Affluence Effect with the Jevons Paradox.

Lacking numbers-based evidence of Jevons at the microeconomic scale, Owens and other Jevons champions pivot to a larger, macroeconomic version: energy efficiency makes our society richer, which increases energy consumption.

But even this assertion is challenged by the numbers. Take a look at these two graphs, again from Goldstein at NRDC:

California energy efficiency measures

<cal-efficiency.jpg>

?

California per capita electricity consumption

<cal-consumption.jpg>

?

?If Jevons applied here, California's efficiency gains would have driven GREATER per capita consumption. Instead, it has SLASHED per capita consumption. Maybe a smart, Jevons-believing economist could unpack the data and prove Jevons lurked here somewhere, perhaps hidden by other variables. But show us the data.

Two recent and related data points are worth noting...both run counter to what we would expect if Jevons were at work at the macroeconomic level:

This is not to say that we're off the hook on our profligate ways. It's well established that affluent societies consume way more energy than poorer ones. And perhaps the wealth-creating effect of energy efficiency plays a role in this dynamic. But even if the Jevons Paradox does have an effect at the macroeconomic scale (meaning overall increases in the energy efficiency of society lead to greater energy consumption), environmental economists point out that a simple green tax (like a carbon tax) would wipe out the effect. And there's a mutually supporting relationship between Passivhaus/passive building and a carbon tax: the carbon tax helps guarantee that building efficiency gains "stick," and the do-ability of Passivhaus/passive buildings makes the carbon tax more palatable.

I know it won't be easy to pass a carbon tax, but here are three reasons for hope:

- 52% of Americans now say they are worried about climate change.

- While any carbon tax initiative will need to battle entrenched dirty energy interests, plenty of one-percenters are freaked out about climate change and have no vested interest in dirty energy...Silicon Valley anyone?

- The same potential for a "black swan" event that fuels nightmares of wholesale ecosystem collapse also applies to positive change and paradigm shifts. Examples: fall of Soviet Union, the imminent solar power tipping point, election of a black President, acceptance of gay marriage, etc.

?

Albert Rooks

Albert Rooks [mobile device]

Zachary Semke

Albert Rooks

Albert Rooks [mobile device]

Hayden Robinson

I would love to see a carbon tax. Coupling the external costs of CO2 emissions with the emissions themselves would give missing feedback to the market. The economic sense of Passive House would also, hopefully, become obvious. I suspect that, even with its economic benefits, and with offsetting tax breaks to make it a win-win, the carbon tax may face staunch opposition from the capitalist right, since a carbon tax would be tantamount to acknowledging that free-market capitalism requires corrective Keynsian intervention. Fingers crossed.

1. It robs the practitioner of perhaps the biggest motivation of his/her work: helping to make a contribution (however small) to the climate solution.

2. It robs "the movement" of a powerful means of attracting new champions.

3. It robs the client of a powerful motivation for building a Passivhaus or passive building. (Health and happiness are important selling points, but every single one of our Passive House clients has expressed concern for climate as a driving part of their decision to pursue a passive building.)

4. It robs us of a powerful argument for including Passivhaus/passive building in building code or incentive programs aimed at reaching things like Climate Action Plans.

5. It plays into the hands of those who prefer the status quo.

For all these reasons, we'd be crazy to assume that the Jevons Paradox applies to the world of Passivhaus/passive building without incontrovertible evidence to prove it is so.

By definition, the Jevons Paradox says that energy efficiency efforts, like Passivhaus and passive building, are counterproductive. That's why the Paradox is also called "backfire". Rebound effects, which are widely accepted as being a normal part of doing energy efficiency work, are not the Jevons Paradox (unless the rebound is greater than 100%, which appears to be very rare).

If the Jevons Paradox tells us "what I'm doing to address energy consumption is counterproductive," a rebound effect tells us "what I'm doing to address energy consumption is less than 100% effective."

Okay that is all - thanks for humoring me. Now onto my reply to Hayden:

Hi Hayden,

I confess to being confused by your statement that I've changed the subject. I started here and here is where I remain:

Hayden, in your last message you included this footnote:

"Increasing aggregate fuel efficiency makes fuel effectively cheaper and more available, which ultimately increases, rather than decreases fuel consumption. At least that's what I'm pondering these days. Hence my thought that energy efficiency and reduced carbon emissions are separate issues, and that the solution to global warming lies elsewhere."

To recap, I think these two ideas are wrong:

1. Increasing fuel efficiency (aggregate or no) increases fuel consumption (aka the Jevons Paradox). (I've only seen evidence that the Jevons Paradox (meaning BACKFIRE, not rebound) applies in very few outlier cases, and I therefore believe it is a red herring.)

2. Energy efficiency and carbon emissions are separate issues and that the solution to global warming lies elsewhere.

Have you changed your mind on these two points? If so then maybe there's no disagreement between us.

My argument, as you'll recall, is this:

1. Economists universally agree that a small rebound effect does exist.

(My Prius example mentioned a 6-8% rebound. This Energy Journal article estimates rebound at 10-30% for residential and transportation sectors, and 0-20% for industries - meaning that energy efficiency measures are 70-100% effective.)

2. You gotta prove it with data or you're just storytelling.

Energy efficiency did not cause fridge size to increase.

3. We shouldn't conflate the Affluence Effect with the Jevons Paradox.

Even the macroeconomic argument for Jevons doesn't appear supported by the numbers.

4. Even if the Jevons Paradox does have an effect at the macroeconomic scale, environmental economists point out that a simple green tax (like a carbon tax) would wipe out the effect.

Skylar Swinford

However there are sadly many more examples of so called free-market economists claiming the negative externalities associated with carbon emissions are not certain enough to justify a carbon tax. If someone has such a hard time trusting climate science I think they ought to question is it because "I don't believe science" or "I don't want to believe it because the science doesn't agree with my politics". If the answer is the latter then that is no excuse and well if it is the former I don't even know what to say.

--

Sent from my phone

Zachary Semke

Albert Rooks

Sent from my iPhone

Zack Semke

Sent from my iPhone

Hayden Robinson

Zack,

From a making-a-difference standpoint, I think it was a super-fruitful discussion. A couple of things stood out:

· From the studies you found, building efficiency measures have been about 80% effective at reducing CO2 emissions. That's pretty dang effective.

· From Prof. York's work, it looks like renewable energy generation comes in at 9% effective.

My take away:

· Efficiency is 9 times more powerful and a much better deal.

· Switching from efficiency to PV at the point of $/kwh parity is false economy.

Getting back to the real-world quandary of my old house, this tells me to stop looking at PV as an easy answer and focus on efficiency measures, even ones that seem too painful and expensive.

Am I missing something here? I really don't want to do something stupid. And those efficiency measure really are expensive and painful.

-H

Hayden Robinson Passivhausdesigner

hayden robinson architect

From: Passive...@googlegroups.com [mailto:Passive...@googlegroups.com] On Behalf Of Zachary Semke

Sent: Friday, April 24, 2015 4:16 PM

To: Passive...@googlegroups.com

Subject: Re: Who's afraid of the big, bad Jevons?

Hi All,

Thanks again for the forum to exchange ideas - I learned a lot from the back and forth about Jevons.

In case you're curious, I just published this post:

Have a great weekend!

Zack

1. It robs the practitioner of perhaps the biggest motivation of his/her work: helping to make a contribution (however small) to the climate solution.

2. It robs "the movement" of a powerful means of attracting new champions.

3. It robs the client of a powerful motivation for building a Passivhaus or passive building. (Health and happiness are important selling points, but every single one of our Passive House clients has expressed concern for climate as a driving part of their decision to pursue a passive building.)

4. It robs us of a powerful argument for including Passivhaus/passive building in building code or incentive programs aimed at reaching things like Climate Action Plans.

5. It plays into the hands of those who prefer the status quo.

For all these reasons, we'd be crazy to assume that the Jevons Paradox applies to the world of Passivhaus/passive building without incontrovertible evidence to prove it is so.

By definition, the Jevons Paradox says that energy efficiency efforts, like Passivhaus and passive building, are counterproductive. That's why the Paradox is also called "backfire". Rebound effects, which are widely accepted as being a normal part of doing energy efficiency work, are not the Jevons Paradox (unless the rebound is greater than 100%, which appears to be very rare).

If the Jevons Paradox tells us "what I'm doing to address energy consumption is counterproductive," a rebound effect tells us "what I'm doing to address energy consumption is less than 100% effective."

Okay that is all - thanks for humoring me. Now onto my reply to Hayden:

Hi Hayden,

I confess to being confused by your statement that I've changed the subject. I started here and here is where I remain:

Hayden, in your last message you included this footnote:

"Increasing aggregate fuel efficiency makes fuel effectively cheaper and more available, which ultimately increases, rather than decreases fuel consumption. At least that's what I'm pondering these days. Hence my thought that energy efficiency and reduced carbon emissions are separate issues, and that the solution to global warming lies elsewhere."

To recap, I think these two ideas are wrong:

1. Increasing fuel efficiency (aggregate or no) increases fuel consumption (aka the Jevons Paradox). (I've only seen evidence that the Jevons Paradox (meaning BACKFIRE, not rebound) applies in very few outlier cases, and I therefore believe it is a red herring.)

2. Energy efficiency and carbon emissions are separate issues and that the solution to global warming lies elsewhere.

Have you changed your mind on these two points? If so then maybe there's no disagreement between us.

My argument, as you'll recall, is this:

1. Economists universally agree that a small rebound effect does exist.

(My Prius example mentioned a 6-8% rebound. This Energy Journal article estimates rebound at 10-30% for residential and transportation sectors, and 0-20% for industries - meaning that energy efficiency measures are 70-100% effective.)

2. You gotta prove it with data or you're just storytelling.

Energy efficiency did not cause fridge size to increase.

3. We shouldn't conflate the Affluence Effect with the Jevons Paradox.

Even the macroeconomic argument for Jevons doesn't appear supported by the numbers.

4. Even if the Jevons Paradox does have an effect at the macroeconomic scale, environmental economists point out that a simple green tax (like a carbon tax) would wipe out the effect.

Zachary Semke

- 9% in aggregate

- 22% for nukes

- 10% for hydro

- No statistically significant data for renewables, as investments in them over the past 50 years have been too insignificant.

- We have no idea how energy efficiency would stack up in York’s rubric. Would it be 20% like nukes or would it, like renewables, not yet register on the radar? (I suspect the latter.)

"In the paper, York essentially tries to determine if the added energy/electricity production from these alternatives actually displaced fossil fuels, or if the increase in capacity just kept up with rising demand..."York found that each kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity generated from non-fossil-fuel sources displaced only 0.089 kWh of that from fossil fuels..."York also looked at the different categories of alternative sources for electricity generation: nuclear, hydro, and non-hydro renewables. Using both models, each kWh of nuclear displaced about 0.2 kWh of fossil fuels, hydro about 0.1, and non-hydro renewables essentially didn’t displace any fossil fuel electricity...[Zack’s NOTE: perhaps a technicality, but the study actually just found lack of statistical significance for the impact of non-hydro renewables - not the same as "essentially didn't displace any."]"Based on these results, it’s clear that alternative energy sources have displaced fossil fuels—but just barely. The main takeaway of the study is that if the same pattern of energy use over the past few decades continues into the future, we will need a massive growth of alternative and renewable sources of energy in order to significantly reduce our reliance on fossil fuels."

Zachary Semke

Hayden Robinson

Zack,

You write a lot! Here's the question I've been trying to answer:

Your research said that efficiency measures are about 80% effective at reducing carbon - how does PV compare?

Thanks,

Hayden

Zack Semke

Sent from my iPhone

Zack,

You write a lot! Here's the question I've been trying to answer:

<image002.jpg>

Hayden Robinson

Thanks for the short answer!

Okay, you suggest starting with efficiency and ending with PV. There's got to be a way to know when to switch. PHIUS's take is: efficiency till a little past $/kwh parity, then PV. Is that good advice?

-H

Zachary Semke

There are lots of folks on this list more expert about PHIUS+ 2015 than me, and better equipped to explore the details with you, Hayden. I’m not your sparring partner on that one.

I will say that I'm excited that PHIUS+ 2015 is addressing the very question you pose: "when to switch?"

I’m also excited to learn more about how PHI is engaging with onsite renewables.

Cheers,

Zack

Tom Balderston

On Thursday, April 9, 2015 at 3:24:09 PM UTC-7, Zack Semke wrote:

Hi All,I’ve really enjoyed reading the conversation about Passivhaus and PHIUS+ 2015. Good stuff.Hayden, in your last message you included this footnote:“Increasing aggregate fuel efficiency makes fuel effectively cheaper and more available, which ultimately increases, rather than decreases fuel consumption. At least that's what I'm pondering these days. Hence my thought that energy efficiency and reduced carbon emissions are separate issues, and that the solution to global warming lies elsewhere.”

I’ve been pondering the same question (aka “The Jevons Paradox”), especially since it played such a starring role in the keynote addresses at PHnw6. In the spirit of dialogue and debate, here’s what I’m concluding from my research so far.

(Apologies for the length of this – I tried to keep it as brief as possible...the reason for all my words?: I’m frankly fairly alarmed by the traction that Jevons seemed to get with our community a couple weeks ago. As you’ll see below, I think the Jevons Paradox is a red herring. To the degree that it causes us to conclude that our efforts are unrelated to reducing carbon emissions, it is also counterproductive.)

“Why I think the Jevons Paradox is hooey, and you should, too.”-OR-“Passivhaus and passive building DO address global warming.”(For folks new to Jevons...) Back in 1865, English economist WS Jevons observed that a new, more efficient steam engine was actually driving increased consumption of coal rather than the expected decreased consumption. The reason: because the new engines used less coal, the price of producing a unit of work with coal dropped, thereby increasing demand for coal. Hence the Jevons Paradox: “Increased efficiency causes greater consumption of a resource, not less.”Now, in our world of super-efficient construction, that’s a pretty shitty message to hear, to put it baldly. If efficiency actually causes consumption, then what’s the point of what we’re doing? Yeah, maybe we’re delivering health and comfort to occupants. And maybe these buildings are resilient places to set up survivalist camps to weather the Apocalypse. But, Jevons, you’re telling me that all my green building good intentions are actually going to hasten climate change??Wow, what a huge bummer.And so counter-intuitive. (Suspiciously so.)What I am uncovering as I delve into the Jevons Paradox, and how an 1865 paper may or may not apply to our world today, is that...1. Economists universally agree that a small “rebound” effect does exist.For example, if I save $100 on gas driving my Prius, in theory I will increase my overall consumption by about $100. Some proportion of that consumption will go to things that burn energy (estimated at 6-8%, the proportion of our economy made up of primary energy). So of the $100 in energy burning that my Prius prevented, I’ll be spending about $6-8 on other energy burning (more miles on my Prius, consumer goods that take energy to produce, etc.) On balance, the efficiency of my Prius saved $92-94 in energy consumption ($100 minus $6-8). Not bad.That $6-8 is the rebound. But it is not proof of the Jevons Paradox. Remember, Jevons says efficiency causes MORE consumption than would have otherwise occurred. So, given that my 50mpg Prius is more than twice as fuel efficient than the average 23.6 mpg US car, my car’s efficiency would have to cause me to more than double my vehicle miles traveled to prove Jevons right. That’s crazy talk. Yes, there’s a rebound effect. But it’s tiny compared to the efficiency gains. (Don’t get me wrong...Priuses are not going to save the world...)2. You gotta prove it with data or you’re just storytelling.At PHnw6 we were shown pictures of double-wide fridges and LEDs on buildings and told stories about how energy efficiency and affluence and profligate consumption are leading us in the wrong direction. It was compelling stuff. I especially liked Lloyd’s cautions about the dangers of being seduced by technology at the expense of nailing the fundamentals of passive building. But the conversation about the Jevons Paradox was about pictures and narrative, not numbers. We didn’t see data to support the causal (or even correlational) claims. And the only way I’m going to accept a notion as counterintuitive and, frankly, show-stopping, as Jevons is if I see some real proof that it applies to our world.Let’s look at the fridges. First, does anyone actually believe that people are buying double-wide fridges now because they are energy efficient? (If Jevons applies to fridge size, then energy efficiency CAUSES increases in fridge size.) A far more likely driver of double-wides is affluence and the big kitchens that wealth makes possible. But let’s look at the data, this from David Goldstein of NRDC:

It shows that expansion of fridge size (the red line) SLOWED significantly just as energy efficiency began to improve after 1972. If Jevons applied to fridges, we should have seen a big spike in fridge size after 1972. That didn't happen so there's no proof of Jevons here. Likely the opposite.

I suspect that the same is true of LEDs. Surely there’s a rebound effect as folks feel freer to use their lights. But I highly doubt that it rises to the level of the Jevons Paradox where LED efficiency actually INCREASES electricity use for lighting. It certainly hasn’t in my house – and we are no saints. And those pictures of LEDs on building exteriors in Asia? That sort of exterior lighting has been going on in Asia for decades – just look at a picture of Tokyo in the 80s, or fire up a copy of Blade Runner again. Lighting efficiency did not create that phenomenon, and likely makes a fairly wasteful practice much more efficient. Am I wrong? Let’s see some numbers.

The reality is that even one of the most prominent champions of the Jevons Paradox (David Owen, author of “The Efficiency Dilemma”) admits that most economists agree that the Jevons Paradox doesn’t apply to our world today. He quotes Stanford University’s Lee Schipper:

“The key to understanding Jevons is that processes, products, and activities where energy is a very high part of the cost – in this country, a few metals, a few chemicals, air travel – are the only ones whose variable cost is very sensitive to energy. That’s it.”

Unfortunately, Owen goes on to ignore Schipper and weave the whole refrigerator yarn again. No data support provided.3. We shouldn’t conflate the Affluence Effect with the Jevons Paradox.Lacking numbers-based evidence of Jevons at the microeconomic scale, Owens and other Jevons champions pivot to a larger, macroeconomic version: energy efficiency makes our society richer, which increases energy consumption.But even this assertion is challenged by the numbers. Take a look at these two graphs, again from Goldstein at NRDC:California energy efficiency measures

California per capita electricity consumption

If Jevons applied here, California’s efficiency gains would have driven GREATER per capita consumption. Instead, it has SLASHED per capita consumption. Maybe a smart, Jevons-believing economist could unpack the data and prove Jevons lurked here somewhere, perhaps hidden by other variables. But show us the data.

Two recent and related data points are worth noting...both run counter to what we would expect if Jevons were at work at the macroeconomic level:This is not to say that we’re off the hook on our profligate ways. It’s well established that affluent societies consume way more energy than poorer ones. And perhaps the wealth-creating effect of energy efficiency plays a role in this dynamic. But even if the Jevons Paradox does have an effect at the macroeconomic scale (meaning overall increases in the energy efficiency of society lead to greater energy consumption), environmental economists point out that a simple green tax (like a carbon tax) would wipe out the effect. And there’s a mutually supporting relationship between Passivhaus/passive building and a carbon tax: the carbon tax helps guarantee that building efficiency gains “stick,” and the do-ability of Passivhaus/passive buildings makes the carbon tax more palatable.I know it won’t be easy to pass a carbon tax, but here are three reasons for hope:

- 52% of Americans now say they are worried about climate change.

- While any carbon tax initiative will need to battle entrenched dirty energy interests, plenty of one-percenters are freaked out about climate change and have no vested interest in dirty energy...Silicon Valley anyone?

- The same potential for a “black swan” event that fuels nightmares of wholesale ecosystem collapse also applies to positive change and paradigm shifts. Examples: fall of Soviet Union, the imminent solar power tipping point, election of a black President, acceptance of gay marriage, etc.

4. ConclusionsThe Jevons Paradox is a molehill, not a mountain.Passivhaus and passive building will be integral to solving the climate crisis, as part of a wildly multi-faceted solution. (Internalizing the externalities of fossil fuel use, through something like a carbon tax, will be vital to this solution.)Let’s hope we put it all together soon.- ZackP.S. What do you guys think? Have you found data that shows Jevons actually applies to our world? Or is it all just smaller rebounds?P.P.S. Some good articles:

Tom Balderston

Zachary Semke

--