Fwd: [jnnurm] What Urbanisation Reforms Owe K C Sivaramakrishnan

Sujit Patwardhan

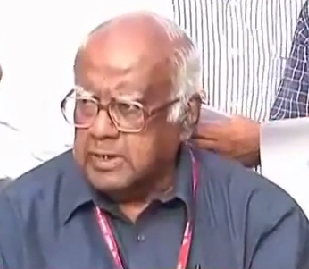

K C Sivaramakrishnan

K C Sivaramakrishnan’s key contribution on metropolitan governance is the articulation of specific recommendations for reforming the current system. He stressed taking a holistic view and having systemic change with democratic decentralisation at the core. He recommended building the governance system anew by creating a metropolitan council at the regional level.

We would like to thank Bhanu Joshi, Partha Mukhopadhyay, Shirish Patel, Abhay Pethe and Vidhyadhar Phatak for their comments. Needless to say, all errors remain our own.

K C Sivaramakrishnan was the rare Indian bureaucrat who championed urbanisation and decentralisation. At a time when cities were regarded at best with suspicion and at worst with open hostility, Sivaramakrishnan recognised their importance. More importantly, he recognised their inevitability and the pressing need to tend to cities for improving governance and accountability of city leadership to the citizens. In his last book, Governance of Megacities: Fractured Thinking, Fragmented Setup, he wrote: “For us in India, there is no escape from urbanization. It is a demographic, economic, and social reality. India has to come to terms with it” (Sivaramakrishnan 2015: xxiv).

Sivaramakrishnan joined the Indian Administrative Service in 1958 and was posted in 1959 as an assistant magistrate on training in Midnapore (currently known as Medinipur). His interest and contribution to the scholarship and policy reform on urbanisation in India was the result of being involved in urban governance first as an officer engaging with the Asansol Planning Organisation and Durgapur Development Authority (1967–71) and later, as the chief executive at the Calcutta Metropolitan Development Authority (1971–75). He moved to Delhi in 1985 in the Ministry of Environment. In 1988, he became secretary at the Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India.

As the chief executive of the Calcutta development authority, he got a first-hand view of the complexities in providing basic services and amenities to citizens in a large city. During his time at the Ministry of Urban Development, he was involved in drafting a Nagar Palika Bill that would be the basis for decentralisation and self-governance for urban local bodies. The motion to pass this bill was defeated in the Rajya Sabha in 1989. In 1992, a version of this bill became the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act, which delineated functions, provided for revenue sharing arrangements between state governments and local bodies, urban planning, and conducting of regular elections.

Since the passing of the Constitutional Amendment Act that ushered in democratic decentralisation for urban India, Sivaramakrishnan has been vocal in highlighting its shortcomings and the manner in which states subverted or even outright flouted the provisions of the act. For instance, he has criticised Article 243Q of the act, which specifies that industrial townships may be exempt from having urban local bodies, stating that it has led to a rise in number of such industrial townships which have no democratically elected political leadership but are instead managed by a board. Public participation in local governance has been deliberately stymied by states who have undermined ward committees. He was also critical of other reforms and institutions that did not uphold the democratic process and the true spirit of decentralisation, which is power to the people or, indeed, that undermined it. He expressed disappointment with Indian courts’ narrow interpretation of decentralisation laws that focused on conducting elections while being silent on transfer of power to the local governments. His commitment to democracy meant that he was sceptical of top-down technocratic solutions like the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission.

Some of the other key issues pertaining to accountability that he raised such as having empowered mayors for cities, the interrelationship between elected representatives and non-elected officials, and the degree of control of the state governments over local bodies continue to be relevant today.

We first met Sivaramakrishnan in 2012 at a workshop that we had organised at University of Mumbai by pure coincidence. He was attending another conference in Mumbai with his colleagues from Centre for Policy Research but he dropped by when he was told that the Department of Economics and Indian Institute for Human Settlements were having a workshop on urban land. As doctoral students working on urban governance and related issues in India, we were well aware of his work. At the time of our first meeting, Sivaramakrishnan was working on a project, which examined the nature of metropolitan governance and service delivery in five Indian megacities—an issue that he remained closely involved with in his final years and that he covered substantively in his final book.

Metropolitan regions in India steadily gained significance as the primate or core cities expanded and people and economic activity began to locate in the urban peripheries. In the 1970s, state governments realised the need for planning for metropolitan regions. This led to the creation of development authorities, which were supposed to play an overarching role for coordination and infrastructure provision at the regional level. The 74th Constitutional Amendment Act also recognised the need for regional planning and recommended the creation of metropolitan planning committees under Article 243ZE. The mandate of these committees was to prepare a draft development plan for metropolitan regions. The composition and other functions to be undertaken by the committee were left to states to determine.

Despite these provisions, over the years, metropolitan regions have witnessed the involvement of multiple organisations with overlapping functions and jurisdictions in public goods and services provision, a multiplicity of planning authorities and plans that are not dovetailed, and an absence of coordination and cooperation for joint provision of goods and services at scale. These issues, however, have largely been neglected and the policy discourse on urbanisation in India has tended to ignore metropolitan governance. According to Sivaramakrishnan,

[n]otwithstanding their enormous demographic and socioeconomic importance, metropolitan cities in India are, as yet, a subject inadequately understood and much less discussed. (2015: xiv)

His book Governance of Megacities: Fractured Thinking, Fragmented Setup—that was the product of his work at the Centre for Policy Research—aims to fill the gap in the policy discourse. It closely examines the nature of metropolitan governance and regional planning, the status of infrastructure, and the demography, economy and ecology for the five largest megacities, namely, Mumbai, Kolkata, Hyderabad, Bengaluru, and Chennai in an attempt to highlight the challenges they face. The book strongly makes the case that these megacities are crucial political constituencies. It traces the evolution of institutions and organisations for the management of these metropolitan regions since colonial times and provides valuable insight into the policymaking process for urban governance in the post-independence period. It also provides a brief overview of the diverse arrangements for governing megacity regions that have been adopted in other countries.

The book is not merely a descriptive treatise; it presents a critique about everything that has gone wrong with the process and outcomes of metropolitan governance in India. In describing the process of identification and delineation of boundaries of metropolitan regions and changes made over the years, it highlights inconsistency in use of criteria for demarcation, the arbitrary and discretionary methods used to change boundaries, and lack of transparency. With regard to the existing governance set-up and the attendant organisations and institutions, Sivaramakrishnan brings to the fore the extreme fragmentation in terms of the number of parastatals, special planning authorities, and other function-specific organisations, apart from urban and rural local bodies, that has made it difficult to coordinate service delivery and plan for the region as a whole. Development authorities have become more interested in management of specific large infrastructure projects instead of being involved in strategic planning for the regions.

At the same time, there is a tendency of state governments to vest control over infrastructure provision at the regional level in their own departments and parastatals. This has resulted in de facto centralisation of power at the state level for matters concerning metropolitan regions. He criticises metropolitan planning committees that were hoped to bring about some coordination at the regional level, as “non-starters.” In a majority of cases, state governments have failed to set up metropolitan planning committees and where they exist, they are virtually without any authority and capacity to fulfil their mandate. Thus the provisions for metropolitan governance and planning in the 74th constitutional amendment have not brought about any favourable changes to the governance system.

Perhaps the key contribution of Sivaramakrishnan’s work on metropolitan governance is the articulation of specific recommendations for reforming the current system. There has been some discussion about the need for reform and the nature of metropolitan governance reforms in recent years. From a policy perspective, the following options exist: a transition to “true polycentricity,” with multiple organisations having overlapping scopes and jurisdictions along with mechanisms for cooperation, efficiency-inducing competition, and dispute resolutions; having a single tier of government at the regional level after consolidating municipalities; or creating an additional tier of government at the metropolitan regional level, between the state and local levels. Gandhi and Pethe (2016) state that the costs of moving towards true polycentricity may be significantly high in India and may outweigh the benefits. With respect to municipal consolidation to a larger scale, there is some public choice literature highlighting the pitfalls of a consolidated government (Boettke et al 2011). Some of the problems with complete consolidation include imperfect information, that is, it is impossible for a government after consolidation to have all the necessary information about citizens’ preferences in order to effectively provide all local public goods and services, and violation of the home rule principle of decentralisation.

Democratic Centralisation

The reforms articulated by Sivaramakrishnan lie in the third category mentioned in the preceding paragraph. He suggests moving away from the present provisions of the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act for setting up metropolitan planning committees altogether. The focus of his proposed reforms is not to merely address the symptoms, which included uncoordinated planning and inefficient provision of services for the regions, but to take a holistic view of the situation and have systemic change with democratic decentralisation at the core. He therefore recommended building the governance system anew by creating a new entity, which may be called a metropolitan council, at the regional level.

For determining the delineation of metropolitan area boundaries, Sivaramakrishnan emphasises the need for transparency and due process requiring approval of the state legislature instead of it being an executive decision. With regard to composition of the council, he recommends, “[it] should reflect a balance of political, professional, private sector, and civil society participation” (Sivaramakrishnan 2013: 239). The body should be headed by a chief executive, elected for a period of five years that is coterminous with the metropolitan council. He suggests that the head be elected indirectly by an electoral college having different segments such as one for the municipal councillors and panchayat leaders, one for members of Parliament and legislative assemblies having their constituencies within the metropolitan region and so forth. Regarding its functional mandate he writes,

a metropolitan council has to be selective in the range of functions it performs. It cannot be a default option for all municipal functions. Its focus should be on those metropolitan-level tasks which will go unnoticed by default, if not performed. (2013: 244)

Some of the functions that could be taken up at the metropolitan level include economic development, regional planning, transport planning, provision of services like solid waste management and water supply, environmental protection, and pollution control. The existing development authorities should be subsumed under the control of the metropolitan council. One aspect of the suggested set-up that could have been elaborated upon is the financial mechanisms or revenue handles that should be provided to metropolitan councils. Without adequate finances, these bodies will be unable to build capacity, hire personnel, and perform their mandated functions.

Bringing about the necessary changes in the governance framework requires an amendment to the current 74th Amendment Act. Sivaramakrishnan’s greatness was evident in the fact that he did not pedantically stick to his old beliefs (he was in effect the author of the 74th constitutional amendment), but was brave enough to call for its amendment in response to the emerging reality (Sivaramakrishnan 2013). At a workshop on urbanisation reforms organised by ICRIER in New Delhi in March 2015, Sivaramakrishnan reiterated the need to re-examine the current governance framework. Calling the amendment “half-baked, half hearted,” he urged those present to seriously think through the modalities for bringing about change.

The 74th amendment can also be amended without too much damage to the Indian constitution but it needs an application of mind and therefore I would request that application to take place. (ICRIER 2015)

Applying our minds in order to propose solutions to the metropolitan conundrum and to see that they are implemented, may be the best way to honour Sivaramakrishnan’s legacy.

References

Boettke, P J, C J Coyne and P T Leeson (2011): “Quasimarket Failure,” Public Choice, Vol 149, Nos 1–2, pp 209–24.

Gandhi, S and A Pethe (2016): “Emerging Challenges of Metropolitan Governance in India,” mimeo.

ICRIER (2015): Capacity Building and Knowledge Dissemination on Urbanisation in India-part 13, video for the “National Workshop on Governance, Administrative Reforms and Capacity Building,” viewed on 31 October 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dK8KgxSxVQQ.

Sivaramakrishnan, K C (2013): “Revisiting the 74th Constitutional Amendment for Better Metropolitan Governance,” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol XLVIII, No 13, pp 86–94.

— (2015): Governance of Megacities: Fractured Thinking, Fragmented Setup, New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sujit Patwardhan

patwardh...@gmail.com

su...@parisar.org

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Yamuna, ICS Colony, Ganeshkhind Road, Pune 411 007, India

Tel: +91 20 25537955

Cell: +91 98220 26627

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------