Cyberseminar statement from Hugo Valin: Modelling the impact of climate change on the food systems through integrated assessments

MUTTARAK Raya

Dear colleagues,

We have received some interesting remarks for yesterday’s statements by Massimo Livi-Bacci and Richard Choularton. The debate on the role population plays on greenhouse gas emissions, food demand and food production is kept lively. Please check out the posts here.

Today we would like to focus the discussion on the statement by Hugo Valin, my colleague from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Austria.

Hugo has walked us through the modelling behind the predictions of climate change impacts on food systems. This is a complex exercise, especially when trying to look at the regional impact. The work presented is mainly based on the Agricultural Model Inter-comparison and Improvement Project (AgMIP).

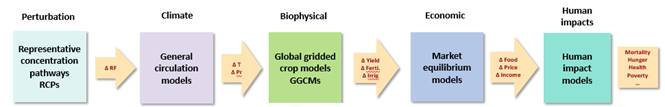

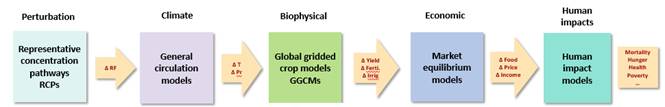

There are several steps to assess the consequences of climate change on food supply and food security, which Hugo has illustrated in his Webminar presentation yesterday.

Hugo also discusses about limitations and uncertainties of the assessment models which depend on regional predictions of the level of warming, assumptions about crop management, the impact of climate change on crop nutrient composition, structural representation and parameterization of economic models, scenarios used for projections of key variables and baseline assumption on food distribution, among other things.

His statement ends with a summary about the progresses and improvement achieved over the past decade in the assessment frameworks such as better incorporation of more socioeconomic and environmental impacts and the recognition of the importance of accounting for adaptation of the food systems.

I highly recommend you to read Hugo’s statement as well as listen to his presentation if you have missed it. (We will post the Webminar online soon).

Looking forward for a lively discussion.

Please send cyberseminar contributions to the email discussion list at pernse...@ciesin.columbia.edu

-- Raya Muttarak, Moderator, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Austria

-- Andres Ignacio, Moderator, Director for Planning and Geomatics, Environmental Science for Social Change, Philippines

-- Susana Adamo & Alex de Sherbinin, PERN Co-Coordinators, CIESIN, Columbia University, USA

Raya Muttarak, DPhil

Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (Univ. Vienna, IIASA, VID/ÖAW)

Deputy Program Director, World Population Program

International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA)

Schlossplatz 1, A-2361 Laxenburg, Austria

Phone : +43 2236 807 329

Fax: +43 2236 71 313

Email: mutt...@iiasa.ac.at,

raya.m...@oeaw.ac.at

Jane O'Sullivan

Thanks to Hugo for a stimulating presentation in the Webinar. He made the very valuable point that modelling so far anticipates only the slow-onset, average effects, whereas extreme events within those averages can have very much greater, and potentially cascading, impacts.

In response to his schematic for modelling climate change impacts, it occurred to me that there is no equivalent effort to model population growth impacts. Population growth will have a far greater impact on future food insecurity and on mass migrations than will climate change. Yet we model population growth as a modifier of climate impact models, rather than modelling climate change as a modifier of population impact models.

This difference in framing has large implications for how risks are perceived and what mitigation is seen as effective. We evaluate population interventions only for their one-dimensional impact on another parameter in the model – such as on energy demand, or on cropping area, without having awareness of the multiple ramifications of a lower or higher population on many environmental, social and economic dynamics. Indeed, there is almost a presumption that addressing population growth will have negative social impacts – hence the reticence to suggest “imposing” such interventions on high-fertility countries before cleaning up rich-world consumption behaviours - as if it is not more the case that we withhold resourcing for family planning, with disregard for (or denial of) the ongoing impoverishment and increasing vulnerability of those communities resulting from population growth.

Jane O'SullivanSent: 20 May 2020 04:37

To: pernse...@ciesin.columbia.edu <pernse...@ciesin.columbia.edu>

Subject: [PERN Cyberseminar] Cyberseminar statement from Hugo Valin: Modelling the impact of climate change on the food systems through integrated assessments

The Population-Environment Research Network (PERN) Cyberseminar Discussion List

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "PERNSeminars - List" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to pernseminars...@ciesin.columbia.edu.

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/a/ciesin.columbia.edu/d/msgid/pernseminars/39a75bf115054e5eb0c667e264d03709%40RHONE.iiasa.ac.at.

Alex de Sherbinin

Reading Hugo Valin's panel statement helped to reinforce something I already knew, which is that the factors affecting food insecurity are many, and that food production alone is not sufficient to explain food insecurity. His careful description of the modeling steps needed in order to arrive at future food availability, and then on to food insecurity, were really helpful.

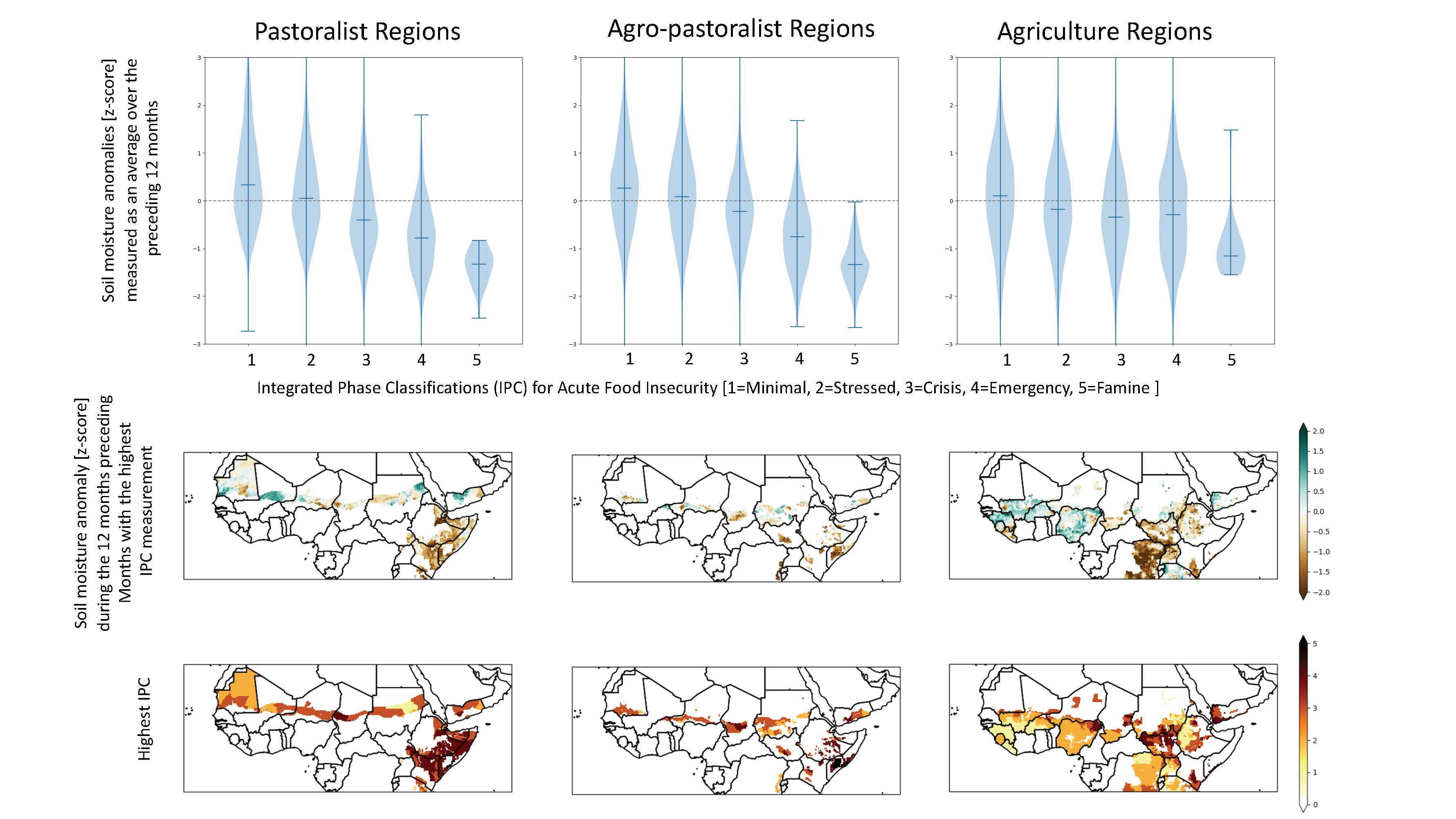

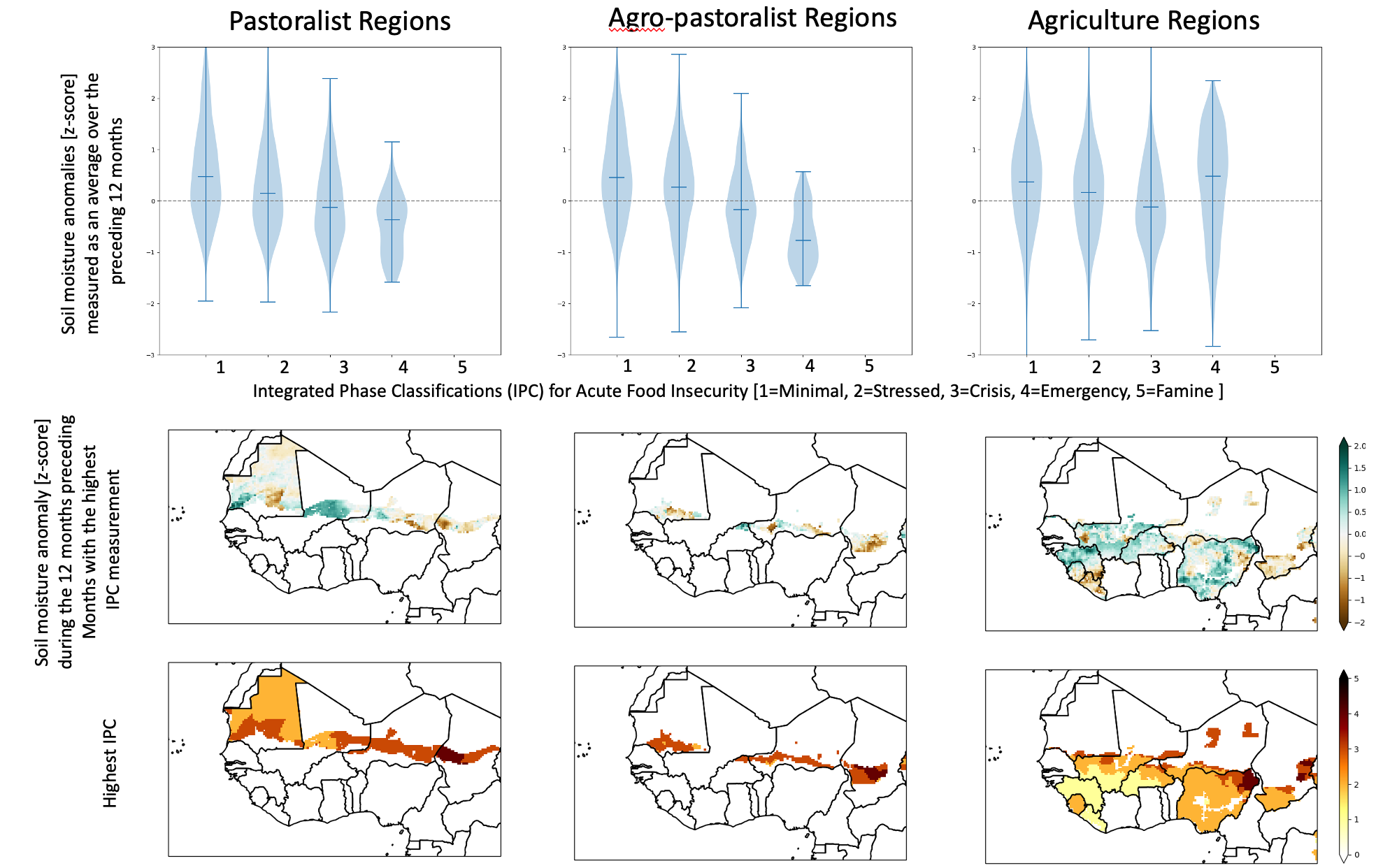

While we will probably never be able to come up with a precise attribution of the climate contribution to food insecurity, recent work by panelist Richard Choularton (Krishnamurthy et al. 2020) and by Weston Anderson here at Columbia demonstrate fairly convincingly that drought events often proceed IPC phases 3-5 (crises, emergency, and famine). Krishnamurthy et al. find that complex weather phenomena (such as ENSO events) are twice as significant as conflict in food security projection errors in the Horn of Africa - meaning that many food insecurity events are not adequately forecast because climatologists were not fully able to anticipate the magnitude of drought in advance. These researchers looked at early warning (forecast events), whereas Weston's work looks at the actual IPC outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa using FEWS NET data.* He found (figure below) that average soil moisture anomalies are, on average, one standard deviation below normal in the 12 months preceding higher order IPC class events. The first row of maps also shows the anomaly levels reported before the highest IPC class events.

On the other side of the coin, I'm aware that "climate change" becomes a convenient scapegoat in many regions where the real underlying factors contributing to food insecurity are governance failures and exploitation (or complete neglect) of smallholder producers. I've been inspired by the work of Ribot et al. (2020), whose detailed examination of the factors driving young males to leave Senegal's peanut basin and to risk everything on a treacherous journey to Europe helps to correct media narratives of "climate refugees". The hungry season before harvest is in fact one of the elements that can explain migration, the hungry season would not be there were there not for systematic disadvantages faced by these agricultural communities because of the way markets for their commodities and inputs are fixed by buyers. The result is a pervasive hopelessness that things could actually change for the better at home.

From a migration perspective, Cascade's question of today is a good one. If the goal of improved agricultural technologies is to lift standards of living, it must be recognized that increased income will likely contribute to even more migration. This should be seen as a sign of success, not of failure, as households seek to diversify incomes. But if there are no viable migration options that do not involve the risk of life and limb for highly uncertain rewards, then this leaves migrants (and the loved ones they leave behind) in a serious quandary.

References

Krishnamurthy, P. K., Choularton, R. J., & Kareiva, P. (2020). Dealing with uncertainty in famine predictions: How complex events affect food security early warning skill in the Greater Horn of Africa. Global Food Security, 26, 100374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100374

Ribot, J., Faye, P., & Turner, M. D. (2020). Climate of Anxiety in the Sahel: Emigration in Xenophobic Times. Public Culture, 32(1), 45-75. https://read.dukeupress.edu/public-culture/article/32/1/45/147856/Climate-of-Anxiety-in-the-Sahel-Emigration-in

* Shared with permission. This work was facilitated by SEDAC development of a new Food Insecurity Hotspots data set using FEWS NET quarterly reports, which will be released shortly at https://beta.sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/data/set/food-food-insecurity-hotspots.

--

The Population-Environment Research Network (PERN) Cyberseminar Discussion List

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "PERNSeminars - List" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to pernseminars...@ciesin.columbia.edu.

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/a/ciesin.columbia.edu/d/msgid/pernseminars/39a75bf115054e5eb0c667e264d03709%40RHONE.iiasa.ac.at.

Alex de Sherbinin, PhD (he/him/his)

Associate Director, Science Applications Division and Sr. Research Scientist

CIESIN, The Earth Institute at Columbia University

Tel. +1-845-365-8936, Skype: alex.desherbinin

Weston Anderson

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/a/ciesin.columbia.edu/d/msgid/pernseminars/CAM942zkT17_bZOPf_SR0iqkGmHAaR_UxQTzs4C4k1ZXXtQq17A%40mail.gmail.com.

Colin Butler

On 23 May 2020, at 3:27 am, Weston Anderson <wes...@iri.columbia.edu> wrote:

Dear All,Just to follow up on Alex's points: While drought is important, in some regions conflict still dominates. Richard and Prasanna noted the impact of both climate and conflict in their analyses, and if you limit the analysis Alex mentions above to West Africa you can see how strongly conflict can confound the relationship between drought and food security: IPC 4 events are associated with wet conditions because these events are primarily related to conflict in NE Nigeria. While there are examples of flooding leading to food insecurity as well (shown nicely by Matthew Cooper here), the metrics we present don't capture that particularly well.

<Screen Shot 2020-05-22 at 1.16.57 PM.png>I'd also follow up on Molly Brown's presentation by pointing out these analyses of what can make a population food insecure should be considered as a function of livelihoods, which is why we present these results in terms of livelihood zone (although it would be preferable to have more complex demographic data since these are very coarse descriptions of livelihoods).Best,Weston

Earth Institute Postdoctoral FellowInternational Research Institute for Climate and SocietyColumbia University

On Fri, May 22, 2020 at 1:10 PM Alex de Sherbinin <adeshe...@ciesin.columbia.edu> wrote:

Dear All,

Reading Hugo Valin's panel statement helped to reinforce something I already knew, which is that the factors affecting food insecurity are many, and that food production alone is not sufficient to explain food insecurity. His careful description of the modeling steps needed in order to arrive at future food availability, and then on to food insecurity, were really helpful.

While we will probably never be able to come up with a precise attribution of the climate contribution to food insecurity, recent work by panelist Richard Choularton (Krishnamurthy et al. 2020) and by Weston Anderson here at Columbia demonstrate fairly convincingly that drought events often proceed IPC phases 3-5 (crises, emergency, and famine). Krishnamurthy et al. find that complex weather phenomena (such as ENSO events) are twice as significant as conflict in food security projection errors in the Horn of Africa - meaning that many food insecurity events are not adequately forecast because climatologists were not fully able to anticipate the magnitude of drought in advance. These researchers looked at early warning (forecast events), whereas Weston's work looks at the actual IPC outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa using FEWS NET data.* He found (figure below) that average soil moisture anomalies are, on average, one standard deviation below normal in the 12 months preceding higher order IPC class events. The first row of maps also shows the anomaly levels reported before the highest IPC class events.

<Anderson FEWSNET analysis 12feb20_Page_1.jpg>

On the other side of the coin, I'm aware that "climate change" becomes a convenient scapegoat in many regions where the real underlying factors contributing to food insecurity are governance failures and exploitation (or complete neglect) of smallholder producers. I've been inspired by the work of Ribot et al. (2020), whose detailed examination of the factors driving young males to leave Senegal's peanut basin and to risk everything on a treacherous journey to Europe helps to correct media narratives of "climate refugees". The hungry season before harvest is in fact one of the elements that can explain migration, the hungry season would not be there were there not for systematic disadvantages faced by these agricultural communities because of the way markets for their commodities and inputs are fixed by buyers. The result is a pervasive hopelessness that things could actually change for the better at home.

From a migration perspective, Cascade's question of today is a good one. If the goal of improved agricultural technologies is to lift standards of living, it must be recognized that increased income will likely contribute to even more migration. This should be seen as a sign of success, not of failure, as households seek to diversify incomes. But if there are no viable migration options that do not involve the risk of life and limb for highly uncertain rewards, then this leaves migrants (and the loved ones they leave behind) in a serious quandary.

References

Krishnamurthy, P. K., Choularton, R. J., & Kareiva, P. (2020). Dealing with uncertainty in famine predictions: How complex events affect food security early warning skill in the Greater Horn of Africa. Global Food Security, 26, 100374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100374

Ribot, J., Faye, P., & Turner, M. D. (2020). Climate of Anxiety in the Sahel: Emigration in Xenophobic Times. Public Culture, 32(1), 45-75. https://read.dukeupress.edu/public-culture/article/32/1/45/147856/Climate-of-Anxiety-in-the-Sahel-Emigration-in

* Shared with permission. This work was facilitated by SEDAC development of a new Food Insecurity Hotspots data set using FEWS NET quarterly reports, which will be released shortly at https://beta.sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/data/set/food-food-insecurity-hotspots.

On Tue, May 19, 2020 at 2:40 PM MUTTARAK Raya <mutt...@iiasa.ac.at> wrote:

Dear colleagues,

We have received some interesting remarks for yesterday’s statements by Massimo Livi-Bacci and Richard Choularton. The debate on the role population plays on greenhouse gas emissions, food demand and food production is kept lively. Please check out the posts here.

Today we would like to focus the discussion on the statement by Hugo Valin, my colleague from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Austria.

Hugo has walked us through the modelling behind the predictions of climate change impacts on food systems. This is a complex exercise, especially when trying to look at the regional impact. The work presented is mainly based on the Agricultural Model Inter-comparison and Improvement Project (AgMIP).

There are several steps to assess the consequences of climate change on food supply and food security, which Hugo has illustrated in his Webminar presentation yesterday.

<image001.jpg>

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/a/ciesin.columbia.edu/d/msgid/pernseminars/CACZ7tq3eubVSoxGFe-gJ7%2BQsd6mp2P9dt%2B%2B8_aHkpBH5Y6uw%3Dw%40mail.gmail.com.

Principal Research Fellow, College of Arts, Humanities & Social Sciences, Flinders University, Australia

https://researchers.anu.edu.au/researchers/butler-cdd

MUTTARAK Raya

Dear Colin,

One way to empirically capture conflict exacerbated by drought is to run a model that first observe drought events at time t-1 and then observe if there is any relationship with conflict occurrence at time t.

We have used this approach to study the relationship between climate, conflict and migration here.

Best wishes,

Raya

Raya Muttarak

On Wednesday, 20 May 2020 13:51:47 UTC+2, Jane O'Sullivan wrote:

Thanks to Hugo for a stimulating presentation in the Webinar. He made the very valuable point that modelling so far anticipates only the slow-onset, average effects, whereas extreme events within those averages can have very much greater, and potentially cascading, impacts.

In response to his schematic for modelling climate change impacts, it occurred to me that there is no equivalent effort to model population growth impacts. Population growth will have a far greater impact on future food insecurity and on mass migrations than will climate change. Yet we model population growth as a modifier of climate impact models, rather than modelling climate change as a modifier of population impact models.

This difference in framing has large implications for how risks are perceived and what mitigation is seen as effective. We evaluate population interventions only for their one-dimensional impact on another parameter in the model – such as on energy demand, or on cropping area, without having awareness of the multiple ramifications of a lower or higher population on many environmental, social and economic dynamics. Indeed, there is almost a presumption that addressing population growth will have negative social impacts – hence the reticence to suggest “imposing” such interventions on high-fertility countries before cleaning up rich-world consumption behaviours - as if it is not more the case that we withhold resourcing for family planning, with disregard for (or denial of) the ongoing impoverishment and increasing vulnerability of those communities resulting from population growth.

Jane O'Sullivan

From: MUTTARAK Raya <mutt...@iiasa.ac.at>

Sent: 20 May 2020 04:37

To: pernse...@ciesin.columbia.edu <pernse...@ciesin.columbia.edu>

Subject: [PERN Cyberseminar] Cyberseminar statement from Hugo Valin: Modelling the impact of climate change on the food systems through integrated assessments

Dear colleagues,

We have received some interesting remarks for yesterday’s statements by Massimo Livi-Bacci and Richard Choularton. The debate on the role population plays on greenhouse gas emissions, food demand and food production is kept lively. Please check out the posts here.

Today we would like to focus the discussion on the statement by Hugo Valin, my colleague from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Austria.

Hugo has walked us through the modelling behind the predictions of climate change impacts on food systems. This is a complex exercise, especially when trying to look at the regional impact. The work presented is mainly based on the Agricultural Model Inter-comparison and Improvement Project (AgMIP).

There are several steps to assess the consequences of climate change on food supply and food security, which Hugo has illustrated in his Webminar presentation yesterday.

Hugo also discusses about limitations and uncertainties of the assessment models which depend on regional predictions of the level of warming, assumptions about crop management, the impact of climate change on crop nutrient composition, structural representation and parameterization of economic models, scenarios used for projections of key variables and baseline assumption on food distribution, among other things.

His statement ends with a summary about the progresses and improvement achieved over the past decade in the assessment frameworks such as better incorporation of more socioeconomic and environmental impacts and the recognition of the importance of accounting for adaptation of the food systems.

I highly recommend you to read Hugo’s statement as well as listen to his presentation if you have missed it. (We will post the Webminar online soon).

Looking forward for a lively discussion.

Please send cyberseminar contributions to the email discussion list at pernseminars@ciesin.columbia.edu

-- Raya Muttarak, Moderator, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Austria

-- Andres Ignacio, Moderator, Director for Planning and Geomatics, Environmental Science for Social Change, Philippines

-- Susana Adamo & Alex de Sherbinin, PERN Co-Coordinators, CIESIN, Columbia University, USA

Raya Muttarak, DPhil

Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (Univ. Vienna, IIASA, VID/ÖAW)

Deputy Program Director, World Population Program

International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA)

Schlossplatz 1, A-2361 Laxenburg, Austria

Phone : +43 2236 807 329

Fax: +43 2236 71 313

Email: mutt...@iiasa.ac.at, raya.m...@oeaw.ac.at

--

The Population-Environment Research Network (PERN) Cyberseminar Discussion List

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "PERNSeminars - List" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to pernse...@ciesin.columbia.edu.

Jane O'Sullivan

Sent: 25 May 2020 15:20

To: PERNSeminars - List <pernse...@ciesin.columbia.edu>

Subject: [PERN Cyberseminar] Re: Cyberseminar statement from Hugo Valin: Modelling the impact of climate change on the food systems through integrated assessments

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/a/ciesin.columbia.edu/d/msgid/pernseminars/88f46d67-c335-48ce-b7a1-9fee62404133%40ciesin.columbia.edu.

Samir K.C.

Please send cyberseminar contributions to the email discussion list at pernse...@ciesin.columbia.edu

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/a/ciesin.columbia.edu/d/msgid/pernseminars/SYYP282MB1167FFA305E31B2AD9F51978A3B00%40SYYP282MB1167.AUSP282.PROD.OUTLOOK.COM.